- 284 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

An Archaeology of the Early Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms

About this book

An Archaeology of the Early Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms is a volume which offers an unparalleled view of the archaeological remains of the period. Using the development of the kingdoms as a framework, this study closely examines the wealth of material evidence and analyzes its significance to our understanding of the society that created it. From our understanding of the migrations of the Germanic peoples into the British Isles, the subsequent patterns of settlement, land-use, trade, through to social hierarchy and cultural identity within the kingdoms, this fully revised edition illuminates one of the most obscure and misunderstood periods in European history.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access An Archaeology of the Early Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms by C. J. Arnold in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Archaeology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

A history of early Anglo-Saxon archaeology

‘Wrapped round with darkness’

Judith, translated by R.Hamer

The purpose of this book is to explore the development of English society during the 200 years AD 500–700 following the migrations of Germanic settlers to the British Isles. The aim is to bridge the gap between the work of specialists whose significance to a general understanding may seem obscure, and generalised accounts that may seem remote from the data. To achieve this we shall be drawing upon the products of archaeologists’ research mostly carried out during the present century. The desire to understand the development of early Anglo- Saxon society as a specific contribution to the more general study of past human behaviour has only emerged in recent years.

Each chapter examines a particular aspect of early Anglo-Saxon society. Such a division is purely a literary convenience and the reader must see each of the topics as intertwined and forming a complex whole. The kingdoms provide the ideal framework for the study of early Anglo-Saxon society as they were developing during the period under consideration. Within that evolving framework there is both complexity and variety, for change involves redundancy as well as novelty, and each region was subject to different pressures stemming from its past and its neighbours.

The archaeological evidence comes from two main contexts: settlements and cemeteries, although earlier archaeologists concentrated on the latter, and especially the artefacts derived from them. The emphasis here is not on a description of the evidence but on its interpretation. To achieve this the data require varying degrees of manipulation if we are to understand the society whose everyday activities constitute the origins of the archaeological record. We will see how the development of Anglo-Saxon archaeology, in which the number of practitioners has always been relatively small, has engendered a conservative approach to the period not suited to answering the fundamental questions relating to human social evolution. In more recent years there have been signs of a change in emphasis. This is reflected in those chapters of this book that deal with the agriculture of the farms and the homes in which our subjects lived, the craft skills in use, trade in commodities and finished products, and their ideas and beliefs, not least the religious beliefs of the population which Christian missionaries so persuasively altered and adapted.

The combination of all such social activities gave a particular character to early Anglo-Saxon society and the manner in which it developed. A major consideration, therefore, has to be a definition of the structure of society, in as far as that is possible, and of the beliefs and bonds that held it together. Naturally the inherent constraints of the archaeological evidence, our caution and increasing enlightenment about the relationship between the archaeo-logical record and the activities that formed it, and the extent of the research that has been carried out determines the cohesion and balance of a work of this type. However, a definition of the current state of understanding and uncertainty should also serve as a diagnosis to guide future research.

The early Anglo-Saxon period is unspectacular and has not been brought to popular attention, except for those rare and fabulous discoveries such as the ship burials at Sutton Hoo (Suffolk). Indeed, there are many people for whom the knowledge that the earliest Anglo-Saxons came immediately after the ‘Romans’ and before the ‘Vikings’ would be a revelation, a shortcoming that the new National Curriculum may manage to overcome. The period is also something of a ‘Cinderella’ within teaching and research in British universities and colleges, there being less than ten specialists teaching under-graduates.

Post-Roman archaeology is one of the younger branches of British archaeology; older established areas of study, such as prehistory, have inevitably tended to form the vanguard of archaeological research, and are more firmly printed on the popular imagination. This may, in part, explain why until recently approaches to early Anglo-Saxon archaeology seemed so distant from those applied to other periods of the past. There has been a degree of inno-cence in much research, with time-honoured methods being applied despite their failure to deepen understanding of the past; techniques applied to other periods tended to be excluded as though they were not relevant to a historic period. While there are indications of increasing experimentation, the reasons for the subject being pervaded by such conservatism and isolationism lie in the history of its development. Its comparative youthfulness and exclusiveness cannot be the sole explanations. A great deal of research in the field during the twentieth century has been carried out by scholars trained, in the first instance, as historians. Eminent scholars working in museums have made an equally significant contribution. They tended to introduce a strong arthistorical bias whose techniques are still utilised, in the rarity of stratigraphic evidence, as a first approach to data in preference to other parameters. These may be the principal factors that have tended to control and limit the nature and scope of research.

Anglo-Saxon remains were first identified correctly in 1793, when an appreciation of the true age of mankind was only just beginning. Possibly the first mention of Anglo-Saxon graves is that by the thirteenth-century chronicler Roger of Wendover in his Flores Historiarum. He describes the excavation of ten human skeletons at Redbourne, Hertfordshire, by monks from St Albans in 1178. They believed some of them were the bones of St Amphibalus (Hewlett 1886:115). Early Anglo-Saxon objects were first illustrated, but not identified as such, by Sir Thomas Browne in Hydriotaphia, or Urne buriall (1658), in which he described the ‘Sad sepulchral pitchers…fetched from the passed world’. To Browne the cemetery at Walsingham, Norfolk, was a reminder of the power of the culture of Rome. One of the forty or fifty burial urns survived in the ‘closet of rarities’ at Lambeth known as Tradescant’s Ark, which in 1682 formed the basis of Elias Ashmole’s bequest to the University of Oxford (Daniel 1981:42). The urns were reported to contain burnt bones accompanied by decorated combs

handsomely wrought like the necks of Bridges of Musical Instruments [and] long brass plates overwrought like the handles of neat implements; brazen nippers to pull away hair…and one kind of Opale, yet main-taining a blewish colour.

Not until the second half of the eighteenth century did any systematic excavation of any early Anglo-Saxon archaeology, a cemetery, take place. The Revd Bryan Faussett carried out a considerable number of excavations in east Kent between the years 1757 and 1777, amassing a total of over 700 graves. It was he who managed the now-famous and hurried disinterment of twenty-eight graves in one day, and nine barrows before breakfast to avoid the disturbance of spectators. Such haste inevitably resulted in cursory recording being a characteristic of research at the time. This is particularly regrettable in Faussett’s case because of the scale of his activities in Kent. Faussett failed to appreciate the true significance of his discoveries. In his journal, kept for the years 1757 to 1773 and published as Inventorium Sepulchrale under the editor-ship of Charles Roach Smith in 1856, he attributed the remains to the period of Roman occupation; Smith preferred a purely British origin.

The credit for first recognising that the ‘small barrows’ were not Roman or Danish, but burial places of the Saxon period, belongs to the Revd James Douglas. He also excavated in Kent, from 1779–93, and published the results in 1793 in his Nenia Britannica (Figure 1.1). Douglas’s work marks a turning point in early Anglo-Saxon archaeology; in the words of Horsfield in his History, Antiquities and Topography of Sussex (1835:11): ‘Up to this time no genuine attempt had been made to acquire knowledge of our early inhabitants, no extensive plan for a generalisation of known excavations.’ Douglas made notable advances in archaeological method, fully appreciating the value of dating by association within and between grave groups. As his biographer has pointed out, in a detailed survey of this period of British archaeology, it was to be a long time ‘before he had an equal in the study of archaeology on a scientific basis or as an illustrator of archaeological relics’ (Jessup 1975:109).

During the second half of the nineteenth century archaeologists advanced the subject in three ways. The first way in which progress was made was by the publication of the results of the excavation of individual cemeteries or of campaigns of excavations. Typical examples include: Wylie’s Fairford Graves (1852), the researches of Lord Londesborough in Yorkshire (1852), and Thomas Bateman’s Ten Years’ Diggings in Celtic and Saxon Grave Hills in the Counties of Derby, Stafford and York, from 1848 to 1858 (1861) (Figure 1.2). Progress was also made by incorporating such reports into early regional studies, such as Knox’s Descriptions Geographical, Topographical and Antiquarian in Eastern Yorkshire, between the rivers Humber and Tees (1855) or George Hillier’s The History and Antiquities of the Isle of Wight in 1856 (Arnold 1978; Hockey 1977), and in more general works such as C.Roach Smith’s Collectanea Antiqua (1848–80). Third, there were early attempts to survey the material as a whole, for instance Akerman’s Remains of Pagan Saxondum (1855). The first attempt to study the subject on a broader basis was by Kemble in his Horae Ferales (1863). For comparative purposes he arranged together types of artefacts from a number of north-west European countries. From these he drew conclusions about the connectedness of artefact types. Although he excavated extensively in Germany, Kemble’s greatest contribution in England was as a historian of the period (1863, 1876). The dominance of the study of grave-goods from cemeteries until the end of the nineteenth century was unavoidable. This source of distortion on our understanding of the period has remained almost to the present day; archaeologists accepted them as a reflection of daily life because they were the only source of data.

Figure 1.1 The title page of Nenia Britannica published in 1793 by the Revd James Douglas

Figure 1.2 Grave-goods excavated by Thomas Bateman at Benty Grange, Derbyshire, in 1848, including the remains of a helmet (source: Bateman 1861:31)

Figure 1.3 An applied saucer brooch from Fairford, Gloucestershire, illustrated by E.T.Leeds in his typological study (source: Leeds 1912:164)

A characteristic of the early twentieth century was the collection of data and their presentation en masse, seen at its best in G.Baldwin Brown’s excep-tional study of much of the material of Anglo-Saxon archaeology, The Arts in Early England (1903–37). Apart from the accumulation of material in this manner the study of early Anglo-Saxon archaeology progressed little. R.A. Smith’s county-by- county surveys appeared in early volumes of the Victoria County History from 1900 to 1926. Such surveys formed the basis for research for many years and still remain the principal source for some cate-gories of data. The format, however, was not conducive to typological study which was beginning to have an impact on archaeology in Britain. In Origin of the English Nation (1907) H.M. Chadwick was the first to attempt a general work on the origins of the Anglo- Saxons by combining historical and archaeological evidence, a theme that has tended to dominate the subject for much of the twentieth century.

The foundations of a mature Anglo-Saxon archaeology were the work of nineteenth-century archaeologists, amongst them Akerman, Roach Smith, Kemble and Wylie. It was the new technique of analysis, typology, which caused the greatest shifts of emphasis in the early years of the twentieth century. Following the publications in England of Oscar Montelius and R.A. Smith (1908; 1905), Edward Thurlow Leeds (Assistant-Keeper and Keeper at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford from 1908 to 1945) produced the first typology of a form of early Anglo-Saxon metalwork, a brooch type (1912) (Figure 1.3). Both he and R.A. Smith, in his British Museum guide to AngloSaxon Antiquities (1923), accepted the importance of the work of the scholar Bernhard Salin, Die altgermanische Thierornamentik (1904). Salin’s analysis of the animal motifs used in migration period art provided a chronology for the English material. Using Smith’s county surveys Leeds was able to extract various classes of object and formulate typologies and chronologies by comparison with the dated developments in Continental art styles.

Figure 1.4 Plan of a building at Sutton Courtenay, Berkshire, excavated by E.T. Leeds (source: Leeds 1936, Figure 9)

E.T.Leeds was also responsible for the first major excavation of an early Anglo-Saxon settlement at Sutton Courtenay, Berkshire (Leeds 1923, 1927, 1947) (Figure 1.4). He also reported on a number of cemeteries (1916, 1924; Leeds and Harden 1936; Leeds and Riley 1942; Leeds and Shortt 1953).

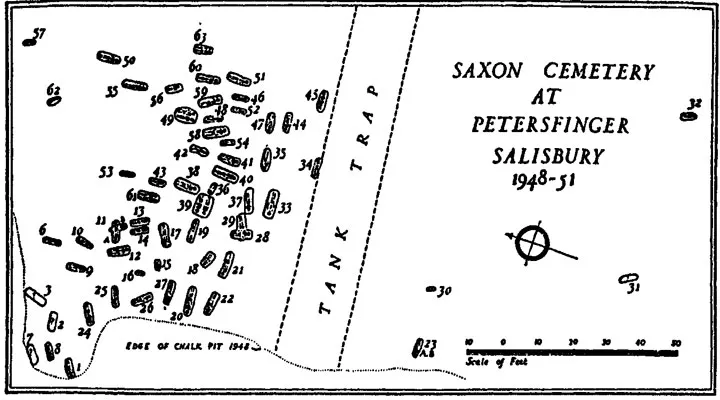

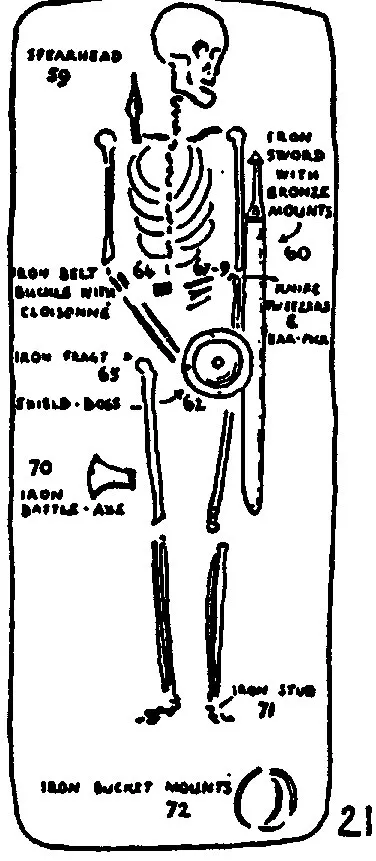

The style of reporting of such excavations changed little, with a plan accompanied by descriptions of graves and their contents. Drawings of cremation urns were provided on a small scale, but with no details of the ‘grave’ or the disposition of the contents. He treated inhumations in a similar fashion, with only some details of the grave, and only late in his career did Leeds provide plans of individual graves (Figure 1.5). Generally, he published photographs of the gravegoods confining line-drawings to more ornate pieces.

Figure 1.5 Plans of the excavated cemetery and grave 21 at Petersfinger, Wiltshire (source: Leeds and Shortt 1953, Figures 2 and (part of) 4)

Leeds was a pioneer in the typological study of artefacts, producing detailed analyses of various brooch types (1912, 1949, 1971 posthumously with M. Pocock). He also grasped the opportunity to synthesise and in 1913 published The Archaeology of the Anglo-Saxon Settlements. This was the first attempt to summarise all of the known archaeology of the period in England and is of interest because it describes the aims and methods of Anglo-Saxon archaeology as Leeds perceived them; there was apparently still a market for the book in 1970 when the publishers reprinted it. He compared the distribution of types of artefact dated by typological methods with historical information, particularly recorded battles between the Anglo-Saxons and the native population. These he saw as marking stages by which the migrants conquered the country. We should note that Leeds was making the distinction between the two races on the basis of the artefacts. For him, an individual using and being buried with an artefact of, ultimately, Continental type was a person of Germanic origin.

This misconception has led many researchers in more recent years to discuss the apparent absence of evidence for members of the native popula-tion. We see Leeds, the culture historian, at his peak in his Early Anglo-Saxon Art and Archaeology (1936) and his paper entitled ‘The distribution of the Angles and Saxons archaeologically considered’ (1945). He believed that if he could attribute the distribution of an artefact type to a particular race or tribe it could indicate the course of the invasion and settlement of England and the origins on the Continent of the settlers. This type of preoccupation was prevalent for much of the twentieth century. During this period Åberg (1926) and Kendrick (1938) produced other valuable studies that also concentrated on art-styles and artefact types.

The method of study developed by Leeds can be traced back in his career as early as 1912; however, it was the prehistorian Gordon Childe who formulated the theoretical framework that stated that prehistoric archaeology should be ‘devoted to isolating such cultural groups of peoples, tracing the differentiations, wanderings and interactions’ (1933:417). Leeds was undoubtedly encouraged to adopt this approach by the historical information provided about the distribution of the Germanic peoples in England by the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People.

Fox took a similar approach in his The Archaeology of the Cambridge Region (1923). In this detailed regional study Fox was concerned with the AngloSaxon invasion and settlement; he also attempted to reconcile distribution maps of artefact types with supposed ethnic groups to the extent of drawing political boundaries. The work of Leeds on Ang...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Figures

- Tables

- Preface to the first edition

- Preface to the revised second edition

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: A history of early Anglo-Saxon archaeology

- Chapter 2: Migration theory

- Chapter 3: Farm and field

- Chapter 4: Elusive craftspeople

- Chapter 5: Exchange

- Chapter 6: The topography of belief

- Chapter 7: Mighty kinfolk

- Chapter 8: Kingdoms

- Bibliography