- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This is Not Architecture assembles architectural writers of different kinds - historians, theorists, journalists, computer game designers, technologists, film-makers and architects - to discuss the characteristics, cultures, limitations and bias of the different kinds of media, and to build up an argument as to how this complex culture of representations is constructed.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

ArchitectureSubtopic

Architecture GeneralPart 1

A Partial History of Virtual Reality

Virtual reality is an old story. Humans have been representing things throughout history. Indeed, it can be argued (as by Pier Luigi Cappucci at a lecture at London’s Royal College of Art on 9 December 1997) that the prolific tendency to represent things is the human’s main distinguishing characteristic.

It is often argued that the emergence of the architect as a recognised professional (as opposed to architecture itself, which is much older) was roughly simultaneous with – and profoundly linked to – the beginnings of perspective. Perspective evolved in the studios of the painters and sculptors of fourteenth-century Florence, overtaking the orthogonal drawings of the Gothic masons’ workshops as the dominant architectural mode;1 and it could be argued that perspective defined architecture as an authored art, rather than a collaborative craft. Since then, the definition of architecture – as an increasingly heavily represented culture before, after and instead of the fact – has been to some extent directed and framed by the tendencies of each medium in which it is shown. Those media used for generating it (such as architectural drawings of all kinds and various types of computer imaging) might have been more influential than those principally used for recording it (photography and film). But all have framed the way architects see the world and design their buildings.

All forms of media – speech, drawing, writing, perspective, photography, film, the various forms of computer information – have their own characteristics, biases and tendencies, as well as their own limitations. Matters outside their scope are implicitly and effectively downgraded – by sheer omission.

By bringing together the four writers in the book who deal directly with what might be called the four big shifts in architectural representation – perspective, photography, film and e-technology – Part 1 gives a kind of summarily assembled history of virtual reality. This is not necessarily the writers’ main subject or their intention, and the contributions are of course offered first and foremost on their own account. But this grouping does allow a consideration of the specific possibilities and limitations of each medium – and what that medium allows us to describe and discuss.

All four writers describe modes of representation that are still current and dominant, and they introduce a field of arguments that connect through the book. In particular, there is the connection between the media’s capacities and conventions and the ways in which we understand what is being represented. There is also the powerful idea that many of the conventions established in one medium are carried through without question into subsequent media (for example, perspective remains extremely dominant in composing photos, films and e-technology) – though of course these conventions are adjusted by the possibilities and limitations of the new medium. These arguments are inherent throughout the book, and it is useful to have them set out in the first instance.

It’s particularly interesting that these four writers use very different types of language. By the final part of the book, which deals with theory, the arguments are often parallel, however diverse the style of writing. At this stage, and as an introduction, it’s useful to see how varied (as well as how similar) architectural writing can be: what sorts of references are used and the audiences that are assumed – indeed, to what extent the scope of a particular type of writing itself shapes the nature of the argument being made.

Note

1 For this analysis I am indebted to James Ackerman’s The Reinvention of Architectural Drawing, 1250–1550, given as the annual lecture at Sir John Soane’s Museum in London 1998, and published by Sir John Soane’s Museum.

Chapter 1

The Revelation of Order

Perspective and Architectural Representation1

Tools of representation are never neutral. They underlie the conceptual elaboration of architectural projects and the whole process of the generation of form. Prompted by changing computer technologies, contemporary architects sometimes recognise the limitations of tools of ideation. Yet, plans, elevations and sections are ultimately expected to predict with accuracy an intended meaning as it may appear for an embodied subject in built work. Indeed, no alternatives for the generation of meaningful form are seriously considered outside the domain of modern epistemological perspectivism – i.e., the understanding of the project as a ‘picture’.

The expectation that architectural drawings and models, the product of the architect’s work, must prefigure a work in a different dimension sets architecture apart from other arts. Yet today, the process of creation in architecture often assumes that the design and representation of a building demand a perfectly coordinated ‘set’ of projections. These projections are meant to act as the repository of a complete idea of a building, a city or a technological object. Devices such as drawings, prints, models, photographs and computer graphics are perceived as a necessary surrogate or transcription of the built work, with dire consequences for the ultimate result of the process. For purposes of descriptive documentation, depiction, construction or any imparting of objective information, the architectural profession continues to identify such projective architectural artefacts as reductive. These reductive representations rely on syntactic connections between images, with each piece only a part of a dissected whole. Representations in professional practice are easily reduced to the status of efficient neutral instruments devoid of inherent value. The space ‘between dimensions’ is a fertile ground for discovery. But the search itself, the ‘process-work’ that might yield true discoveries, is deemed to have little or no significance.

This assumption concerning the status of architectural representation is an inheritance from the nineteenth century, particularly from the scientistic methodologies prescribed by Jean-Nicolas-Louis Durand in his Précis des Leçons d’Architecture (1802 and 1813).2 Durand’s legacy is the objectification of style and techniques, and the establishment of apparently irreconcilable alternatives: technological construction (functional) versus artistic architecture (formal), and the false dichotomy of necessary structure and contingent ornament. Though the formalisation of descriptive geometry in Durand’s design method promoted a particularly simplistic objectification, the projective tool is a product of our technological world, grounded in the philosophical tradition of the Western world. It is one which we cannot simply reject – or simplistically pretend to leave behind.

A different use of projection, related to modern art and existential phenomenology, emerged from the same historical situation with the aim of transcending dehumanising technological values (often concealed in a world that we think we control) through the incorporation of a critical position. A careful consideration of this option, often a central issue in the artistic practices of the twentieth-century avant-garde, may help regenerate architecture’s creative process, bringing about a truly relevant poetic practice in a Post-Modern world.

Gordon Matta-Clark, Office Baroque or Walk Through Panoramic Arabesque (1977). The photograph, a literal section through the visual cone, destructures the reductive quality of section by presenting the actual ‘sectioning’ of an existing building and revealing its otherwise hidden interiority.

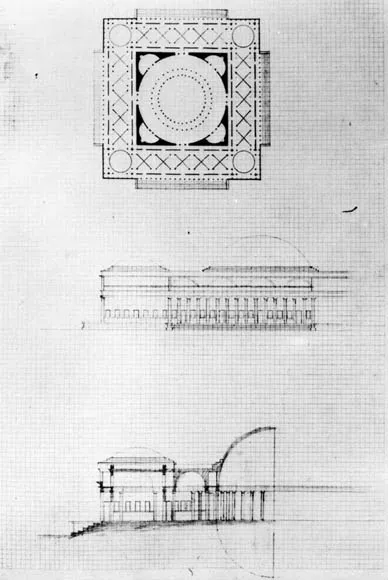

J.-N.-L. Durand’s ‘mechanism of composition’ was the basic design tool in his Précis. The grid became an indispensable modular framework for architectural design in the student projects of the École Polytechnique and the École des Beaux Arts.

Today we recognise serious problems in our post-industrial cities and our scientistic way of conceiving and planning buildings. Even the most recent applications of computers to generate new (and structurally ‘correct’, i.e. ‘natural’) architectural forms assume an instrumental relationship between theory and practice in order to bypass the supposedly old-fashioned prejudice of ‘culture’, (i.e., the personal imagination), with its fictional and historical narratives. It is imperative that we do not take for granted certain scientific assumptions about architectural ideation, and that we redefine our tools in order to generate meaningful form.

Philosophers at the origins of our tradition perceived projection as the original site of ontological continuity between universal ideas and specific things. The labyrinth, that primordial image denoting architectural endeavour, is a projection linking time and place, representing architectural space: the hyphen between idea and experience, which is the place of language and culture, the Greek chora. Like music (realised only in time and often from a notation), architecture is itself a projection of architectural ideas, horizontal footprints and vertical effigies, disclosing a symbolic order in time, through rituals and programmes. Thus, contrary to Euclidean ‘common sense’, depth is not simply the objective ‘third’ dimension. Architecture concerns the making of a world that is not merely a comfortable or practical shelter, but that offers the inhabitant a formal order reflecting the depth of our human condition, analogous in vision to the interiority communicated by speech and poetry and to the immeasurable harmony conveyed by music.

There is an intimate relationship between architectural meaning and the modus operandi of the architect, between the richness of our cities as places of imagery and reverie, as structures of embodied knowledge for collective orientation, and the nature of architectural techne, the differing modes of architectural conception and implementation.3 Since the Renaissance, the relationship between the intentions of architectural drawings and the built objects that they describe or depict has changed. Though subtle, these differences are none the less crucial.

When one examines the most important architectural treatises in their respective contexts, it becomes immediately evident that systematisation, which we take for granted in architectural drawing, was once less dominant in the process of development from the architectural idea to the actual built work. Prior to the Renaissance, architectural drawings were rare. In the Middle Ages architects did not conceive of the building as a whole, and the very notion of a scale was unknown. Gothic architecture, the most ‘theoretical’ of all medieval building practices, was none the less still a question of construction, operating through well-established traditions and geometrical rules that could be directly applied on a site that was often encumbered by older buildings, which would eventually be demolished. Construction proceeded by rhetoric and geometry, raising the elevation from a footprint, while discussions concerning the unknown final figure of the building’s face continued almost until the end. The master mason was responsible for participating in the act of construction, in the actualisation of the city of God on earth. Only the Architect of the Universe, however, was deemed responsible for the conclusion of the work at the end of time.

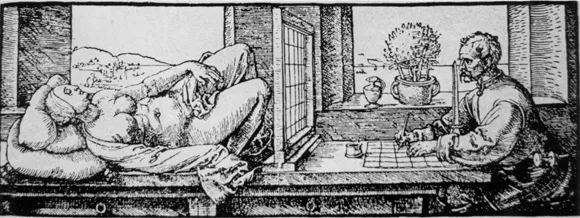

One of Dürer’s several illustrations of perspective devices, from his Underwysung der Messung (1538). A draughtsman uses a grid and an eyepiece to draw a nude figure with the correct proportions required by foreshortening.

During the early Renaissance, the traditional understanding of architecture as a ritual act was not lost. Filarete, for instance, discussed in his treatise the four steps to be followed in architectural creation. He was careful to emphasise the autonomy among proportions, lines, models, and buildings, describing the connection between ‘universes of ideation’ in terms analogous to an alchemical transmutation, not to a mathematical transformation.4 Unquestionably, however, it was during the fifteenth century that architecture came to be understood as a liberal art, and architectural ideas were thereby increasingly conceived as geometrical lineamenti, as bi-dimensional, orthogonal projections.

A gradual and complex transition from the classical (Graeco-Arabic) theory of vision to a new mathematical and geometrical rationalisation of the image was taking place. The medieval writings on perspective (such as those of Ibn Alhazen, Alkindi, Bacon, Peckham, Vitello and Grossatesta) had treated, principally, the physical and physiological phenomenon of vision. In the cultural context of the Middle Ages its application was specifically related to mathematics, the privileged vehicle for the clear understanding of theological truth. Perspectiva natural...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Notes on contributors

- Illustration credits

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Part 1: A partial history of virtual reality

- Part 2: The shape of representation

- Part 3: The reporting of architecture

- Part 4: The construction of theory

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access This is Not Architecture by Kester Rattenbury in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.