- 296 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Principles of Project and Infrastructure Finance

About this book

Current books on project finance tend to be non-technical and are either procedural or rely heavily on case studies. In contrast, this textbook provides a more analytical perspective, without a loss of pragmatism.

Principles of Project and Infrastructure Finance is written for senior undergraduates, graduate students and practitioners who wish to know how major projects, such as residential and infrastructural developments, are financed. The approach is intuitive, yet rigorous, making the book highly readable. Case studies are used to illustrate integration as well as to underscore the pragmatic slant.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Principles of Project and Infrastructure Finance by Willie Tan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Project Management. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

1.1 Purpose of this book

The purpose of this book is to provide a guide on the principles of project and infrastructure finance to students and practitioners.

By “principles,” we mean a set of rules or claims about the nature of something. Principles tend to be general or universal, and go beyond specific ways of financing individual projects. They are developed by abstracting from “reality” (or “facts”) to isolate only the essential elements for analysis. The non-essential elements are ignored. For any set of essential elements, further approximations (such as absence of friction in physics or a featureless plain in models of city form) are then made to develop general models that can subsequently be applied to specific cases.

Sometimes, the model assumptions are not approximations of reality but are quite unreal. Simple examples include the assumption of a closed economy in Keynesian economics and the assumption in neoclassical growth theory that an economy produces only one homogeneous good. In a globalized world, the assumption of a closed capitalist economy is clearly unrealistic. As for growth theory, even Robinson Crusoe produces more than one good.

However, the intent is not so much to reflect or construct “reality” but to invoke obviously unreal assumptions as a pedagogic device to start with a simple model and progressively make it more and more realistic (or “concrete”) by relaxing these assumptions. Once we understand how a closed economy operates, the next step is to consider what happens in a more complicated open economy with external trade and investment.

These principles should be simple to understand and not be unnecessarily cluttered with details. For instance, one does not begin by teaching students how to solve

1.23x2 + 2.234x + 23.54 = 0

even though it may be encountered in practice. Instead, one starts with a simpler structure such as

x2 + 2x + 1 = 0

and explore possible solutions. The first equation is no more “practical” than the second one. From a pedagogic viewpoint, the second equation is more “practical” in teaching students how to solve quadratic equations. As is well known, there is nothing as practical as a good theory to guide us.

1.2 What is project finance?

Project finance is a form of financing a capital-intensive project (such as an infrastructure project) on non-recourse or limited recourse basis through a special project vehicle (SPV).

The recourse for lenders is primarily the revenues generated by the project for loan repayment with project assets as collateral. Unlike corporate finance, lenders do not have recourse to the assets of the sponsors (e.g. the parent corporation) should the project fail.

This special non-recourse or limited recourse feature makes project finance attractive to sponsors because financing is off-balance sheet. It does not jeopardize the parent company’s ability to borrow funds for other purposes or investors’ assessment of its liabilities in the balance sheet.

However, with the trend towards better corporate governance and greater transparency, corporations are generally required to report material off-balance sheet items at least in the footnotes of their annual or quarterly reports. The disclosure covers debt and guarantees as well as purchase, lease, and contingent obligations.

For lenders, pure non-recourse lending is risky and they usually require some limited form of contingent financial support from sponsors over and above their equity share as well as other forms of credit enhancements and third-party guarantees. For instance, if the borrower is a local public agency, the government may be called to guarantee repayment or provide limited contingency support if the project is delayed and requires additional funds.

Since projects are capital-intensive and interest on debt is deductible in the computation of corporate tax, project financing is highly levered to about 60 85 per cent of project cost. In many cases, equity from a sponsor or a few sponsors is insufficient because of the large investment and the desire not to make the SPV a subsidiary. Hence, the equity must be supplemented by funds from other (possibly passive) equity investors.

On the debt side, lending is often syndicated under a lead bank or arranger to pool the funds and spread the risk among a few lenders. In more lucrative projects, it may be possible to issue local, regional or global bonds (particularly when the project is near completion, thereby removing a substantial part of the construction risk) to attract funds from other investors. Once a project is completed, a permanent lender (such as a mutual fund, real estate investment trust, or insurance company) takes over the loan from the syndicate of construction lenders. Usually, securing a permanent loan first makes it easier for the borrower to obtain a construction loan. There are, of course, many other variations in project financing.

It can be seen that project finance is complicated to arrange, and this raises the issue of the cost of arranging such a loan. However, without this form of financing to pool resources and share the risk, many projects may never have gotten off the ground.

1.3 History of project finance

The origin of project finance is obscure. In Antiquity, the construction of large-scale infrastructure was largely financed by the State through taxation or looting of the assets of enemies. Constrained by inadequate finance and absence of long-term debt, many such projects were built in stages using forced and unproductive labor and took a long time to complete even if they were uninterrupted by wars and bad weather.

During the Middles Ages, merchants began raising money to finance shipping. However, because of the high risk, prospectors had only limited recourse if a ship sank. Some bridges, canals, and roads were also financed by apportioning shares to each member of the community, a procedure that could potentially lead to disputes over whether the ability to pay principle or benefit principle should apply when it came to charging fees. Money for repairs and maintenance was also raised in a similar manner, although some river and road tolls were “simply extortion” and not for improvements and were levied when “higher political authority could not prevent robber barons and local jurisdictions from levying on passersby” (Landes, 1999, p. 245). Even when tariffs were set, the toll-takers made it a point not to publish them so that they could change the levy “as opportunity offered” (p. 246). Grand churches and monasteries were also built either from church coffers or endowments. As a powerful medieval institution, the church was able to amass large tracts of land bequeathed by childless widows of warring knights killed in battles.

With the advent of capitalism, money was also raised to finance railways and real estate in places such as India, Africa, the Americas, Malaya, Australia, and New Zealand in the 19th century. For short railways, finance was arranged locally normally through share issues to friends, farmers, manufacturers, miners, and other prospectors. Information on the new railway technology, location of minerals, soil conditions, reputation of promoters, and labor problems were too sparse for these speculative projects to attract external finance. Larger projects were able to attract the interests of investment houses after colonial States were asked to guarantee minimal rates of return (Thorner, 1951). That is, if a project did not provide sufficient return on a bond, the State would pay the difference between the declared return (e.g. 8 per cent) and what the project company paid out (e.g. 5 per cent). Many of these State-backed bonds were floated in London to tap surplus British capital. Typically, investment houses bought shares or bonds to signal confidence in their advice to British investors.

As cities boomed, developers began to set up separate special purpose vehicles to raise funds and protect their liabilities should a project fail. To limit their equity, end-user finance was also used in the form of progress payments from buyers of real estate under construction. Many of these projects were speculative in the sense that they were built in anticipation of demand rather than at the request of home owners. Since such demands were cyclical and volatile, the risks and pay-offs were high.

After World War II, large-scale infrastructure was largely financed by the State through tax revenues, borrowings, or simply over-printing of money by tolerating “some” inflation. This expansionary approach was in line with the idea of State-led development using State planning and Keynesian deficit finance to raise aggregate demand during a downturn and achieve full employment. As the economy recovers, tax revenues will rise and State expenditure can be scaled back. In theory, the budget surplus during a boom will be used to cover the deficits incurred during a downturn. In practice, government spending can spin out of control as politicians seek re-election and make too many promises.

The classic case for State subsidy of large-scale infrastructure projects rests with the external benefits brought about by the improved infrastructure. In addition, in the 1950s and 1960s, few private firms were able to undertake such huge and lumpy projects without State assistance or assurances against confiscation of project assets or changes in taxes or regulation.

As we have just seen, the subsidy took the form of State guarantee of the interest on bonds. State guarantees ensured that projects were attractive enough to be financed externally but it also weakened the profit incentive for promoters and sponsors. It encouraged mismanagement, looting, over-promotion, inflated prices, and ruinous competition. Not surprising, there were spectacular failures (Grodinsky, 2000; Nairn, 2002).

In the developing countries, domestic savings were supplemented by foreign aid and funds from lending international agencies. Since

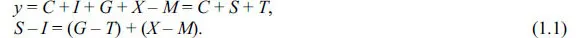

Here y is real gross domestic product or national income. It is equal to the sum of private consumption expenditure (C), business fixed investment and residential investment expenditure (I), government expenditure (G), and net exports (exports less imports, or X − M). The national income is also the sum of consumption expenditure, savings (S), and taxes (T). Equation (1.1) shows that there are three well-known “gaps” to bridge in economic development (Chenery and Bruno, 1962):

- a “savings gap” in the private sector,

- a government budget deficit, and

- a trade deficit.

These gaps may be “plugged” by mobilizing domestic savings, balancing the State budget, and overseas borrowings or through external aid.

At the local government level, tax-exempt revenue bonds were used to finance the revitalization of many cities (particularly in the United States) through urban renewal. This method is still in use; the destruction of the American Gulf Coast by hurricanes Katrina and Rita in 2005 also led to bond issues based on utility tariffs rather than assets to rebuild the infrastructure.

In the energy sector, private firms began to use project finance to tap rapidly developing capital markets for mineral, oil, and gas exploration (e.g. North Sea oilfields). In addition to equity and traditional bank lending, international bonds were also used to raise large sums of money simultaneously worldwide. During the inflationary 1970s and early 1980s, debt financing was attractive to investors since repayments were made in cheaper dollars.

In the 1990s, the securitization of assets became popular to “unlock” asset value and provide liquidity to owners. Many large commercial developments were securitized and bought by Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs). Dividends from these trusts were attractive to many small investors because of tax benefits. For instance, in the US, REITs are not taxed on the income distributed to shareholders if at least 90 per cent of the ordinary taxable income is distributed annually as dividends. This avoids the usual double corporate taxation on profits and dividends paid to shareholders.

The swing against “big” governments towards free markets for greater efficiency and transparency led to the development of public-private partnership (PPP) projects. As we saw earlier, large-scale infrastructure projects from the 1950s to the 1970s were largely owned by the government and funded from domestic savings, taxation, and overseas borrowings or through foreign aid. This strained the budgets of many governments, and PPP projects were conceived as a way for the State to partner the private sector in developing such projects. The private sector provides the badly needed funds and expertise.

1.4 Approaches to project finance

Generally, approaches to project finance may be categorized as follows:

- procedural, such as Pahwa’s (1991) book on Project Financing. The 1136-page book is replete with policies, rules, forms, annexes, and checklists;

- case study-centered, for example, Lang’s (1998) book on Project finance...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Abbreviations and notations

- Preface

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Time Value of Money

- 3. Organizations and Projects

- 4. Corporate Finance I

- 5. Corporate Finance II

- 6. Project Development

- 7. Social Projects

- 8. Characteristics of Project Finance

- 9. Risk Management Framework

- 10. Risk, Insurance, and Bonds

- 11. Cash Flow Risks

- 12. Financial Risks

- 13. Agreements, Contracts, and Guarantees

- 14. Case Study I: Power Projects

- 15. Case Study II: Airport Projects

- 16. Case Study III: Office Projects

- 17. Case Study IV: Chemical Storage Projects

- Appendix: Cumulative standard normal distribution

- References

- Index