- 228 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In Roman Jakobson Richard Bradford reasserts the value of Jakobson's work, arguing that he has a great deal to offer contemporary critical theory and providing a critical appraisal the sweep of Jakobson's career.

Bradford re-establishes Jakobson's work as vital to our understanding of the relationship between language and poetry. By exploring Jakobson's thesis that poetry is the primary object language, Roman Jakobson: Life, Language, Art offers a new reading of his work which includes the most radical elements of modernism. This book will be invaluable to students of Jakobson and to anyone interested in the development of critical theory, linguistics and stylistics.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Roman Jakobson by Richard Bradford in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

The poetic function

METAPHOR AND METONYMY

The bipolar opposition between metaphor and metonymy is crucial to our understanding of Jakobson’s notion of language and literature as at once co-dependent and autonomous sign systems. We will begin with some basic descriptions and illustrations.

When we construct a sentence—the most basic organisational unit of any speech act or parole—we draw both upon the rules and conventions of the syntagmatic chain, in normative terms grammatical regulations, and upon the more flexible dimension of paradigmatic choices available at each stage in this process. I’ll give an example:

His car moved along the road.

The syntagmatic chain consists of a main verb ‘moved (along)’, two nouns ‘car’ and ‘road’ and a pronoun and definite article, ‘his’, ‘the’. If we wanted to offer another version of the same message we could maintain the syntagmatic (also known as combinative) structure but make different choices from the paradigmatic (also known as selective) pole at each stage in the sentence. For instance,

The man’s motor vehicle progressed along the street.

The only substantive difference occurs in the substitution of street for road, suggesting as it does an urban environment; and indeed such changes as the above are generally made in order to clarify the message. To this end we might substitute ‘sped’ for ‘moved’ or ‘progressed’ to indicate that the car is moving faster than we would normally expect So far we have drawn upon the paradigmatic pole and produced slight variations upon the same prelinguistic event. In short, we have attempted to employ language as a mimetic or transparent means of representation: the perceived speed of the car motivates alterations in our linguistic account. Jakobson associates the paradigmatic pole with the construction of metaphor, a linguistic device that is generally classified as a literary, or more specifically a poetic, figure, and this raises a question regarding the distinction between our ‘ordinary’ use of the paradigmatic pole and our use of it as a means of creating a metaphor. We might engage with the latter by stating that

His car flew along the road.

This is an, albeit unexciting, metaphoric usage because, although we have maintained the conventions of the syntagm (‘flew’ like ‘moved’ is a verb), we have also made an unexpected choice from the paradigmatic-selective bag. Cars do not fly, but, since the flight of birds and aeroplanes is generally associated with degrees of speed and unimpeded purpose, we have offered a similarity between two otherwise distinct fields of perception and signification. We have used the contextual relation between two classes of verbal sign to move beyond the mode of clarifying the event, have intervened as an active perceiver and offered an impression of the event—the movement of a car reminds us of the progress of a bird or aeroplane.

We should now consider the relation between the metaphoric dimension of the paradigmatic-selective pole and the metonymic dimension of its syntagmatic-combinative counterpart. Metonymy has usually been considered by conventional literary critics and theorists to be an element or subdivision of metaphor. It is also known as synecdoche, the substitution of part for whole or vice versa. Jakobson has not redefined metonymy; rather he has promoted it from the status of a decorative literary figure to a comprehensive, universal category as the ‘other half’ of all linguistic design, structure and construction: all sentences rest upon an axis between the metaphoric and metonymic poles.

A metonymic version of our sentence could be,

His wheels moved across the tarmac.

Here an element has been substituted for the whole (wheels for car, tarmac for road). This might seem metaphoric but in effect we have only deleted one element of the original semantic construct. To have metaphorically selected or substituted one for another we might have replaced ‘wheels’ with the phrase ‘his last refuge’ or with ‘his heart’s delight’, which tell us something about, in our view, the man’s relationship with his car, but which are not directly related to its physical or contextual dimensions.

Jakobson’s distinction between the metaphoric and metonymic poles is a heuristic device, a tool which enables the analyst to dissect and categorise the structural and functional elements of language. As such it can run dangerously close to showing us the parts while obscuring or even falsifying the ways in which they actually combine and interrelate. Jakobson is, as we shall see, fully aware of this danger.

The principal problem with the two poles stems from their representation in explanatory texts in terms of visual diagrams. For example, the following columns are often used to illustrate homologous relations between the two halves of the linguistic process.

| Paradigm | Syntagm |

| Selection | Combination |

| Substitution | Contexture |

| Similarity | Contiguity |

| Metaphor | Metonymy |

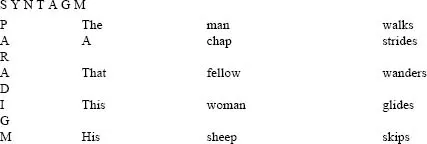

These columns are frequently adapted to horizontal-vertical representations of the specific selections and combinations available in given sentences.

In the second diagram any alternative combination of the given instances of article/pronoun, noun and verb is possible—‘His man wanders’, ‘That sheep strides’, ‘A woman walks’, etc. In this respect the two diagrams are a useful means of illustrating how the two poles of language operate, but they are necessarily restricted by their self-determined contexts. For example, if we were to state that The tree wanders’, we would maintain the relationship between the two abstract conceptions of the poles but in specific terms the statement would not make sense.

Jakobson’s work on metonymy and metaphor is at its most detailed and intensive in his treatment, during the 1950s, of the linguistic disorders of aphasia. This work is summarised in the 1956 essay on ‘Two Aspects of Language and Two Types of Aphasic Disturbances’ (1956, in SW II and in L in L). Consider the problem raised by ‘The tree wanders’ in relation to Jakobson’s thesis, which is as follows.

Jakobson relates combination and the syntagm to ‘context’. This term is double-edged: it can refer to the internal linguistic context in which the meaning of a word is influenced by its relation to other parts of the syntactic pattern; or it can refer to the broader notion of a prelinguistic situation which in some ways affects the construction of a statement. Jakobson, in this essay, posits a necessary causal relationship between the contexture of the syntagm and the correspondence between language and its situation.

…selection (and correspondingly, substitution) deals with entities conjoined in the code but not in the given message. The addressee perceives that the given utterance (message) is a combination of constituent parts (sentences, words, phonemes) selected from the repository of all possible constituent parts (the code).

(L in L, p. 99)

Note that the ‘message’, the particular statement which creates for the addressee or receiver a productive interface between word(s) and meaning, is linked with the combinatory, syntagmatic pole, while the ‘code’, the enabling system of relationships between classes and types of words, is linked with the paradigmatic, selective pole. So if we, as addressees, were to encounter the sentence ‘The tree wanders’, we would be able to decode it as a message because of its maintenance of a recognisable combinatory sequence, article-noun-verb. But in the process of decoding we might also be rather perplexed by the resulting paraphrase (what Jakobson refers to as the metalanguage, or ‘language about language’). Trees do not by their own volition or motor power ‘wander’. In short, we have made sense of a message that in any empirical or scientific context does not make sense. The ‘code’, the system which makes the verb ‘wander’ available as an alternative to more usual terms such as ‘falls’, ‘sways’ or even ‘is moved’, is clearly in conflict with the message. From this we might surmise that the syntagmatic, combinative pole is that which anchors language to the prelinguistic world of events and impressions, while its paradigmatic, selective counter-part is that which effects a more subjective and perhaps bizarre relationship between the mind of the addresser and the code of linguistic signs. Jakobson substantiates this thesis in a typically economic, and some might argue enigmatic, manner. ‘Whether messages are exchanged or communication proceeds unilaterally from the addresser to the addressee, there must be some kind of continuity between the participants of any speech event to assure the transmission of the message’ (L in L, p. 100). Note how the word ‘contiguity’, like ‘context’, is double-edged. It refers at once to the contiguous relationship between signs and the similarly contiguous relationship between addresser and addressee, speaker and hearer. In short, our most basic communicative interactions involve us in following the linear, combinatory movement from word to word; addresser to addressee cohabit within the syntagm, ‘a kind of contiguity between the participants of any speech event’. But the selective pole, that which feeds more readily upon the code, is more closely associated with the individual addresser. ‘Within…limitations we are free to put words in new contexts… the freedom to compose quite new contexts is undeniable, despite the relatively low statistical probability of their occurrence’ (L in L, p. 98). This freedom to compose is exhibited by the addresser who states that trees can wander. He/she could also state that trees can shop, swim, weep, smoke, sail, fly, copulate….

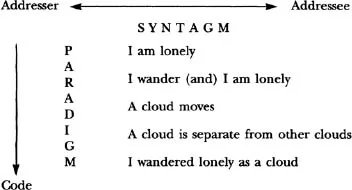

Let us now return to the diagrammatic representations of the two poles. They are at once useful and deceptive; useful in the sense that they graphically represent the binary opposition upon which our analysis of language is based, deceptive because they discriminate between and equalise two elements of the linguistic process that, for both addresser and addressee, are in practice in a constant state of interpenetration and sometimes conflict. The following is a revised version of the second diagram:

The final statement is, you will note, borrowed from William Wordsworth. I do not claim that the transformations and additions listed represent a record of Wordsworth’s actual process of composition, but let us, for the sake of convenience, assume that they might. The addressee is led by the addresser along the syntagmatic chain and in this process they share the condition of cohabitants within this communicative dimension. It is likely that the addressee will have already encountered the phrases ‘I am lonely’ or ‘I wandered’, but it is less likely that he/she has encountered a comparison between these existential and active states; ‘there must be a certain equivalence between the symbols used by the addresser and those known and interpreted by the addressee’ (L in L, p. 100). But the concatenation of wandering, loneliness and cloud (iness) fractures this agreed consensual balance between the use and interpretation of the two poles. The addresser, standing at the axis between the poles (see diagram) disrupts the usual expectation of code in relation to message, paradigm to syntagm: a ‘normal substantive illustration of wandering or loneliness would be something like ‘as a beggar’ or some other isolated human presence.

Jakobson’s use of the term ‘equivalence’ in the above sentence is another instance of the conflation of the internal mechanics of the linguistic system with the condition of its users. In the former case equivalence means the equation between the two poles: if two terms or words are equivalent they are substitutable in the same place in the syntagm. In the latter, this same equation is promoted to the context or the mental condition of expectations shared by addresser and addressee in their encounters with language and the prelinguistic world: ‘the separation in space, and often in time, between two individuals, the addresser and addressee, is bridged by an internal relation’ (L in L, p. 100). I mention this case because the term reappears in what must be the most widely quoted statement from Jakobson’s work: ‘The poetic function projects the principle of equivalence from the axis of selection into the axis of combination.’ This statement occurs in his massively influential 1960 essay on ‘Linguistics and Poetics’. Its meaning and its significance have been rigorously debated, but to understand it properly we must consider its origins in Jakobson’s treatment of aphasia.

Jakobson identifies two types of aphasic condition, the similarity disorder and the contiguity disorder. The similarity disorder (also known as selection deficiency) involves the aphasic sufferer in a condition of enclosure within the syntagmatic, combinative chain, and as such this person becomes overdependent both upon the contexture of linguistic integers and upon concrete, non-verbal elements of his/her immediate situation.

It is particularly hard for him to perform, or even to understand, such a closed discourse as the monologue…. The sentence ‘it rains’ cannot be produced unless the utterer sees that it is actually raining. The deeper the utterance is embedded in the verbal or nonverbalised context, the higher are the chances of its successful performance by this class of patients.

(L in L, p. 101)

This condition of enclosure within the contextural, combinative dimension also restricts the aphasic’s ability to distinguish between ‘object language’ (the actual message) and ‘metalanguage’, a circumlocution or equivalent version of the same intended meaning. The object language-metalanguage relationship is regarded by psycholinguists as a vital element in all forms of human dialogue, and is particularly important in child language acquisition. For example, if we are uncertain of the meaning of a statement we can request clarification. The speaker will then substitute equivalent terms from the agreed paradigmatic bag. To return to our original examples, if asked what we meant by the sentence ‘The car moved along the road’, we could substitute ‘flew’ as a means of specifying the unusual speed of the vehicle. A person with a similarity disorder will be unable to make such substitutions, and Jakobson gives an example of how such a person deals with this problem.

When he failed to recall the name for ‘black’ he described it as ‘What you do for the “dead”’. Such metonymies may be characterised as projections from the line of a habitual context into the line of substitution and selection: a sign (fork) which usually occurs together with another sign (knife) may be used instead of this sign.

(L in L, p. 105)

Jakobson’s statement is intriguing and, in relation to his definition of the poetic function, disturbing. In effect, the ‘projection’ achieved by the aphasic is virtually identical to that of the poet, albeit in reverse: the poet projects from the selective to the combinative axis, while the aphasic projects from ‘the line of habitual context into the line of substitution and selection’. In both instances a disruption is caused between the matching of the two axes and the expected correlation between linguistic usage and context.

With the contiguity disorder, ‘the patient is confined to the substitution set (once contexture is deficient) [and] deals with similarities, and his approximate identifications are of a metaphoric nature, contrary to the metonymic ones familiar to the opposite type of aphasics’ (L in L, p. 107). The result of this condition is the diminishing of the coherent structure and variety of sentences; the usual grammatical order of words becomes chaotic, ties between coordinate and subordinate terms are lost. In short, the ‘contexture-deficient’ aphasic is confined within the paradigmatic dimension, a world in which signs relate primarily, sometimes exclusively, to other semantically connected signs and become resistant to the contextual dimension of the syntagm and prelinguistic circumstances. The type of aphasia affecting contexture tends to give rise to infantile one-sentence utterances and one-word sentences’ (L in L, p. 107). Again we might be prompted to compare the condition of the contiguity disorder aphasic with that of the poet, particularly the modernist poet. The early modernist school of Imagist poetry is often characterised by lists or columns of phrases, sometimes individual words, which defy the normal rules of consecutive logic. The classic case is Pound’s ‘In a Station of the Metro’:

The apparition of these faces in the crowd;

Petals on a wet black bough.

Pound does not state whether the faces of the crowd are like or unlike the petals on the bough; nor does he indicate the circumstances which prompted him to bring these two phrases together: did the petals on the bough remind him of the faces in the crowd or vice versa? In his essay Jakobson quotes Hughlings Jackson, a nineteenth-century pioneer of investigations into language disturbances: ‘without a proper interrelation of its parts, a verbal utterance would be a mere succession of names embodying no proposition’. This seems an accurate summary of the effect created by Pound’s poem. To return to the concept of metalanguage, we might claim that while the similarity disorder aphasic is excluded from the dialogic function of circumlocution or paraphrase, his contiguity disorder counterpart is enclosed within this same function to the extent that it isolates similarities between words and phrases from their usual relationship with the prelinguistic context. The similarity disorder patient could continue endlessly to extend a sentence through sets of known and contiguous circumstances, and the contiguity disorder patient could reach further and further into his own repertoire of word connections, endlessly substituting one element of his personal paradigmatic repertoire for another.

We (he) could continue Pound’s poem:

The train on the track

The blue pattern and the grey

The fish on the scales

The moment and the lifetime.

Jakobson’s investigations of aphasic disorders seem to interpose linguistics and by impli...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Editor’s foreword

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Notes on the references and bibliography

- Introduction

- Part I The poetic function

- Part II The unwelcoming context

- Part III Space and time

- Suggestions for further reading on context and influence

- Bibliography

- Index