- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Begins by identifying a global problematique, a coincidence of four sustained factors; war, insecurity and militarisation; the persistance of poverty, the denial of human rights; environmental destruction. The conventional policy approaches to these problems are analysed through a rigorous critique of the three United Nations reports of the 1980s. Describing the partial solutions of the Brandt, Palme and Bruntland Commissions, attention is turned to the individuals and organisations involved in policy and action at the grassroots level. Peace and security, human rights, economic development are all discussed. The author argues that if the root causes for crisis lie in Western scientism, developmentalism and the construct of the nations state, it is on the success of `alternative' work that a new world order, based on peace, human dignity and ecological sustainability, can be created.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A New World Order by Paul Ekins in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Économie & Théorie économique. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

ÉconomieSubtopic

Théorie économique1

THE GLOBAL PROBLEMATIQUE

THE MILITARY MACHINE

The essential statistics of military power are readily accessible. There are three principal categories of weapons of mass destruction, nuclear, chemical and biological. The nuclear category has received the most public attention and its extent can be briefly summarised. Five nations—China, France, the UK, US, and USSR—admit to being nuclear-armed, though several other countries, including Israel and South Africa, are known to have nuclear weapons, and several others, including Brazil, India, and Pakistan are thought to have a nuclear capability. Proliferation of nuclear weapons is likely to spread even more widely if civil nuclear reactors continue to be constructed in otherwise non-nuclear countries. There is an abiding danger that the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, which up to 1990 had remained practically a dead letter in terms of the nuclear disarmament it envisaged, will become one with regard to non-proliferation also.

The vast majority of nuclear weapons are held by the two superpowers, the US and USSR, who in 1989 were thought to have some 55,500 warheads between them, 98 per cent of a world total which has a combined power of 1,200,000 Hiroshima-type bombs (Sivard 1989, p.9). It is estimated that this amount, 1, 000 times the firepower used in all wars since the introduction of gunpowder six centuries ago, could destroy the planet at least twelve times over (Sivard 1986, p.7). While it might be thought that this overkill represented the apogee of nuclear deterrence and that efforts might therefore be turned to maintaining rather than increasing or improving this destructive power, this is far from being the case. Arms levels grew inexorably through the 1980s (at least until the accession of Mr Gorbachev). The US in particular still strives to improve the stealth and accuracy of its nuclear weapons, against all deterrence logic. In proceeding with SDI (the ‘Star Wars’ Strategic Defense Initiative), which by 1989 had cost US$17 billion (Sivard 1989, p. 15), the US continues to signal to the USSR and the world in general that it wishes to obtain invulnerability from nuclear attack and so break the balance of deterrence in its favour. It is not just the USSR that has legitimate causefor concern if the US became able to deploy its firepower free from risk of retaliation.

While nuclear weapons have long attracted great public interest and debate, chemical weapons have recently become an increasingly serious source of concern. The proven use of these weapons by Iraq in the Iran—Iraq war and the general perception of that use as having been both militarily successful and relatively costless politically, have caused chemical weapons to be widely perceived as ‘the poor countries’ nuclear weapon’, due to their relative ease and cheapness of manufacture. Prospects for a worldwide ban on the development, production and possession, as well as use, of chemical weapons, a convention which has been in preparation since 1969 by the forty-nation Conference on Disarmament in Geneva, have accordingly receded. Unless agreement is reached quickly, it is likely that even medium to small states in the Third World will either have acquired or be able quickly to acquire chemical weapons should they wish to do so.

One of the very few significant measures of arms control before the recent US/USSR agreement on intermediate range nuclear weapons was the Biological Weapons Convention of 1972, ratified by 105 nations, which forbade the development, production and stockpiling of these weapons, as well as ordering the destruction of existing stocks. However, under the guise of research into defence against biological weapons, up to ten countries are now thought to have potentially offensive research programmes under way in this field. Advances in biotechnology and genetic engineering have enormously increased the potential for the development of lethal organisms, and it seems only a matter of time before these too become routine, if unadmitted, components of many arsenals.

While the weapons of mass destruction occupy the high-profile end of the military spectrum, they account for only a small proportion, less than 20 per cent (Sivard 1989, p.33) of global military spending, which in 1988 amounted to approximately US$1,000 billion (Sivard 1989, p.12). This sum buys not only military hardware. It employs well over half a million scientists and engineers in military research and development. It puts some 25 million people into uniform. It is hard to envisage the opportunity cost of US$1,000 billion except by reference to the estimated cost of various international programmes which have been devised to tackle major generally-recognised problems in other areas: the FAO/UNDP/World Bank/World Resources Institute Tropical Forestry Action Plan, US$8 billion over five years; the UN Water and Sanitation Decade’s plan of action to bring clean water to every citizen in the world by the year 2000, US$300 billion over the 1980s; the 1977 inter-governmental plan to halt the spread of deserts, US$90 billion over the last two decades of the century (MacNeill et al. 1989, p.10); UNICEF’s estimate of ‘the additional cost of meeting the most essential of human needs’ of everyone on earth, a maximum of US$500 billion over ten years (UNICEF 1989, p.65); extending the World Health Organization’s Expanded Programme on Immunization to all Third World children, US$2 billion (Sivard 1989, p.33). It can be easily seen that these large programmes, none of which has yet been anywhere near implemented, would all fit comfortably within one year’s global arms expenditure.

If the military expenditure could be shown to have prevented war, then at least it might be seen to have some justification. Unfortunately this is far from being the case. From 1945-89 some 127 wars occurred round the world, killing an estimated 22 million people and injuring countless others (Sivard 1989, pp. 11, 22). In 1988 some 27 wars (annual deaths exceeding 1,000) were being fought (Sivard 1987, p.28). Because most of them were being fought with modern imported weapons they were much more destructive than if each country had had to rely on its own weapons capability. The global trade in arms, principally supplied by France, the UK, US and USSR, with Brazil and India being increasingly prominent Third World arms manufacturers, ensures that the most modern means of killing people are quickly accessible to any government in the world.

It is often argued that nuclear deterrence has, at least, kept the peace in Europe since 1945 and prevented nuclear war. The argument is also heard that the recent superpower detente and agreement was due to NATO’s bargaining from strength, by which is meant its decision in 1979 to deploy Cruise and Pershing missiles.

Both these arguments exhibit the post hoc ergo propter hoc logical fallacy. Just because one event succeeds another, it does not follow that it was caused by it. It is just as logical to assert that forty years of European peace have been achieved and that nuclear war has so far been avoided in spite of the policy of nuclear deterrence, with all its attendant risks of bluff, brinkmanship, misunderstanding and mistake. Similarly it can just as logically be argued that Mr Gorbachev was only able to gain support within the USSR for his arms control proposals because of the huge manifestation of public opinion against the Cruise and Pershing decisions in both Europe and the US, which reassured the Soviets that despite the tough NATO stance, Western publics were deeply desirous of an end to the Cold War, as has subsequently been proved by Mr Gorbachev’s popularity with those publics.

The root cause of wars and the arms race is as old as recorded history itself: aggression, on the one hand, and consequent insecurity on the other. Some countries acquire arms to attack others. Others acquire them for defence. Most claim the latter motivation but ensure that they purchase arms which will serve eitherpurpose, either because of secret aggressive intent or because they genuinely believe that the best form of defence is attack

Security acquired through weapons is, at best, a zero-sum good: one side’s greater security is another’s increased vulnerability (defence-only weapons can invalidate this equation, but they are still very much the exception rather than the rule). This is what puts the spiral into the arms race as each country seeks its own security at another’s expense. After each round, security is likely to have diminished at higher cost, because both sides are more heavily armed with more deadly weapons. An opportunity cost of the weapons is a missed chance to strengthen both country’s economic and social infrastructure.

It is extremely unlikely that, in a world where nuclear, chemical and biological weapons are commonplace, they will not be widely and catastrophically used sooner or later. The insecurity engendered by large arms arsenals, intertwined with the other crisis-insecurities of mass poverty, ecological destruction and population repression, and combined with all the other factors of race, ideology, expansionism and religious belief which have traditionally led to conflict, all mean that wars in today’s world are likely to increase in number and intensity for as long as security is perceived as emanating from the barrel of a gun.

THE HOLOCAUST OF POVERTY

Poverty is both an absolute and relative phenomenon. The absolute variety afflicts about one billion people, the 20 per cent of the world population that is not able on a regular basis to satisfy their most basic human subsistence needs. In consequence the lives of these poor tend to be short. UNICEF has estimated that 15 million children die each year from such poverty.

If absolute poverty is basically a physical condition, relative poverty is more a function of expectations and opportunity in a particular society. A basket of goods or skills which, in one society, may confer self-respect and social worth and usefulness may, in another, bring only alienation, isolation and despair. The psychical component of relative poverty has special implications for attempts to relieve it as will become clear.

Whereas the great majority of the absolutely poor live in the Third World, the relatively poor are concentrated more in industrial countries. In the UK in 1987 over 10 million people, (nearly a fifth of the population, were living in poverty (Oppenheim 1990, p.1). Few of these if any will be actually starving. Most will be relatively poor. There is plenty of evidence that relative poverty is as excruciating in its own way as the absolute variety. Its influence can cause people to turn to drugs, violence and crime. It breaks up families, destroys sociability and induces profound personal stress.

As with war, poverty, especially of the absolute kind, seems long to have been an integral part of the human condition. The difference between poverty and war, and the disappointment, lies in the fact that forat least the past 100 years in industrial countries, and forty years in the so-called ‘developing’ world, economic growth is supposed to have been leading inexorably to the abolition of poverty. That is what the whole project of ‘development’ was all about.

The reality has been quite different. There is little evidence that absolute poverty is generally onan established downward trend. In many countries of the Third World, especially in Latin America and Africa, it is clear that the reverse is the case. For example, in Sub-Saharan Africa:

- per capita incomes have fallen by almost 25% during the 1980s;

- investments have fallen by almost 50% and are now in per capita terms lower that they were in the middle of the 1960s;

- imports are today only 6% of per capita imports in 1970;

- exports have fallen by 45% since 1980;

- the external debt has grown from $10 billion in 1972 to a staggering $130 billion in 1987. The capacity to service it has not kept pace, thus creating an unmanageable situation for some twenty low-income countries;…

- the share of children starting school is beginning to decline and in some places the infant mortality rate is on the increase.

(Swedish Ministry of Foreign Affairs 1988, p.11)

In many cases it is not lack of ‘development’ that has brought popular impoverishment, but ‘development’ itself, as when natural resources that provide a decent subsistence livelihood for large numbers of people are turned into industrial raw materials that benefit relatively few. Those who are displaced or dispossessed or both probably began neither absolutely nor relatively poor. While modest, their lives are likely to have been both self-sustaining and commensurate with their expectations and those of their peers. They will have been useful, productive members of their society.

After the ‘development’ project, be it large dam, plantation, logging, or industrial fishery or whatever, these people will be both absolutely and relatively poor: ill-fed, ill-clothed, and ill-housed and transplanted from their traditional society into one of quite different values and priorities in which it is extremely difficult for them to participate. An excellent current example of this tragic process can be seen in the Narmada Valley Project in India’s States of Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra, described in some detail in Chapter 5. The two largest dams involved in this project will between them displace over 200,000 people, many of them tribals, who will have their villages and fields totally or partially flooded. Despite state government rhetoric, there is not the remotest prospect that sufficient fertile land will be found elsewhere to give these people independent livelihoods. Cut off from their traditions, their communities destroyed, the vast majority of the displaced will drift to the slums of Bombay or Ahmedabad, like countless development refugees before them. Such rural-urban migration has historically been a common factor of all industrialisation. The agricultural beneficiaries from the dam, at least before it silts up and before the salinisation of irrigated land, will be predominantly existing farmers and landowners, while the urban middle and industrial classes will be the main users of the hydro-electricity. There is ample evidence that wealth accruing to these social groups in developing countries does not trickle down to the poor, beyond the relatively small amount of direct employment that is generated. Rather the income differentials between the landless and dispossessed, and the rest, are increased and poverty intensified. As for drinking water, another supposed benefit of the dam, there are grave doubts that the project will even deliver this resource over the hundreds of kilometres required to reach the poorest peoples in the most arid lands, who are often cited as the project’s main justification.

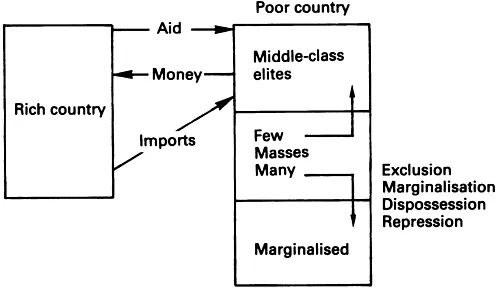

One of the reasons why developing country wealth does not reach the poor is that those who control it tend to be more interested in Western markets and Western lifestyles. Their purchase of Western armaments and consumer goods does nothing to give livelihoods to their own people. Paradoxically, therefore,

Figure 1: The ‘aid and development’ cycle

‘development’ can end up giving more benefit to the rich countries which provided the initial ‘aid’ than to the poor people in the countries which received it. This sort of development cycle can be pictured as in Figure 1. It is because of this sort of cycle that increasing numbers of grassroots activists in Southern countries are regarding ‘development’ as dangerous to and exploitative of poor people in poor countries.

THE ENVIRONMENTAL CRISIS

For most of the past ten years it has been necessary to argue forcefully against general scepticism that there is in fact a serious environmental crisis of global dimensions, but public awareness has changed dramatically since about 1987 so that general concern for the environment has now forced the issue near the top of the international political agenda.

As with armaments and poverty, the problem is quite simply stated: the ability of the biosphere to support and sustain human, animal and plant life is being severely eroded by the numbers of people on the planet and the impact of their economic activities.

Standard environmental economic analysis now recognises that the environment contributes to human life in three fundamental ways. It provides resources for the human economy; it disposes of the wastes from that economy; and it directly provides services for people in many different ways, some of an aesthetic nature by way of amenity (e.g. countryside, scenery, wilderness), and some that are crucial to survival, (e.g. regulation of the climate and atmosphere). It is interesting to note that the first focus of environmental concern was predominantly on the first of these environmental functions, the provision of resources. The Club of Rome’s landmark publication Limits to Growth (Meadows et at. 1972) raised questions about the future supply of minerals and fossil fuels at pertaining (and increasing) levels of consumption. Fifteen years later the attention is much more on the limited ability of the environment to absorb the wastes of the economic process, and the consequent impact of those wastes on the great life-regulating biosystems and on human health. The now familiar litany of pressing problems includes global warming through the emission of the so-called greenhouse gases (carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide and chlorofluoro-carbons [CFCs]), acidification of lakes and forest die-back due to the emission of sulphur dioxide, nitrogen oxides and ozone, depletion of the ozone layer by the emitted CFCs and the generation of increasing quantities of hazardous (chemical or radioactive) wastes.

Interacting with these waste-disposal effects is the ongoing global destruction of bioresources, expressed, though not exhaustively, in such words as deforestation, desertification and species extinction. More than 40 per cent of the world’s original 6 million sq. miles of tropical forests have already disappeared and continue to do so at a rate of 30,000-37,000 sq. miles every year, with a similar area suffering from gross degradation (Myers 1986a, p.9); 6 million hectares are added to the world’s deserts each year, with an area larger than Africa and inhabited by 1 billion people now at risk; topsoil is being lost at an estimated 25 billion tons per year, roughly the amount covering Australia’s wheatlands (MacNeill et at. 1989, p.5); and Norman Myers has estimated that, at present rates, hundreds of thousands of species will be extinguished over the next twenty years from only 400,000 sq. miles of prime tropical forest (Myers 1986a, p.12). Theability of the biosphere to sustain such damage into the future without major climatic or other upheavals is to be doubted.

THE DENIAL OF HUMAN RIGHTS

Amnesty International (AI) reported that in 1988 it investigated or adopted people as Prisoners of Conscience (those imprisoned solely because of their belief, sex, ethnic origin, language or religion and who have neither used or advocated violence) in eighty-four countries (Amnesty International 1989, p. 17). In the same year AI brought to the attention of the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture cases from forty-three countries (ibid. p.23). Ruth Leger Sivard’s research indicates that there are sixty-four military regimes in the Third World (Sivard 1989, p.21).

There are no simple reasons for human repression on this scale just as there are no simple solutions to it. Certainly the situation is exacerbated by the three problems discussed earlier—war and the arms race, poverty and maldevelopment, and environmental destruction—and by the streams of refugees to which each of these problems give rise. But equally it can be said that there has been a massive failure on behalf of the most democratic nations of the world to give practical effect abroad to their widely professed rhetoric in support of human rights, especially...

Table of contents

- COVER PAGE

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT PAGE

- FOREWORD

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- INTRODUCTION

- 1: THE GLOBAL PROBLEMATIQUE

- 2: THE NEED FOR APPROACHES

- 3: PEACE THROUGH PUBLIC PRESSURE AND REAL SECURITY

- 4: IN DEFENCE HUMAN RIGHTS

- 5: CONTRASTS IN DEVELOPMENT

- 6: DEVELOPMENT BY PEOPLE

- 7: ENVIRONMENTAL REGENERATION

- 8: FURTHER ASPECTS OF HUMAN DEVELOPMENT

- 9: CONCLUSION

- APPENDIX 1: THE RIGHT LIVELIHOOD AWARD AND ITS RECIPIENTS, 1980–90

- APPENDIX 2: ADDRESSES OF PRINCIPAL ORGANISATIONS MENTIONED

- BIBLIOGRAPHY