- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Realist Novel

About this book

This book guides the student through the fundamentals of this enduring literary form. By using carefully selected novels and discussing a wide range of authors including Emily Dickinson and John Kincaid, the authors provide a lively examination of the particular themes and modes of realist novels of the period. This is the only book currently available to provide such a wide range of primary and secondary material and is the prefect resource for a literature degree.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Realist Novel by Dennis Walder in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

Chapter One

The genre approach

by Dennis Walder

Introduction

Approaching literature through study of its genres has been fundamental to literary criticism in the European languages since Aristotle’s Poetics in the fourth century BC. What Aristotle did was, first, to gather as many examples of a given literary phenomenon as possible and then, by observing resemblances, differences and alliances, to extract from these examples a few general descriptive principles. This is the approach he used, for instance, when preparing to analyse tragedy. Tragedy, he said, was a serious, dramatic representation of an important human action, arousing pity and fear so as to purge those emotions. Tragedies had unity (beginning, middle and end), plots and characters. The hero was a person of significance who was flawed…and so the analysis proceeded.

This way of defining a type of literary work on the basis of its characteristic features has been employed throughout the history of western literature from Greece and Rome through the Middle Ages to the Renaissance and then to our own time. It is an approach that has always had its followers, although it has varied in impact and acceptance.

In eighteenth-century Europe, for instance, it was common to think of literature as being modelled on the ‘classical’ genres of Greece and Rome, such as tragedy or epic. ‘Imitating’ earlier works was considered a high endeavour. There was a hierarchy of literary forms, and the best way of expressing yourself was to find the one most suitable for what you had to say. This view was summed up in what was called ‘decorum’. Towards the end of the eighteenth century a contrary view developed, stressing the original and individual in creative works rather than their closeness to earlier models. Nowadays most people would probably say that what is most important is the individual encounter with a particular work, rather than its classification. Nevertheless, literary works are still classified for particular purposes, by or on academic syllabuses, and there have always been people who believe in approaching works of literature (or art) in terms of their shared features.

In his widely influential Anatomy of Criticism (1957) the critic Northrop Frye set out to establish a comprehensive and systematic account of all literature in terms of what he called genre archetypes. Other critics, such as Wayne Booth (in The Rhetoric of Fiction, 1961), have applied this approach to a single genre, analysing its typical features in great detail. More recently, a general interest in genre has reasserted itself as a way of understanding the generation of meaning through the way one literary text is like or relates to others. Those who use the term nowadays usually do so to indicate that in literature broad forms of expression can be identified, and that it is worth looking at particular works in relation to these broad forms, and each other.

All this can appear rather complicated, but two trends in thinking about literary genres may be distinguished.

- The idea that literary genres are fixed or transcendent types which stay the same, and to which individual works may or should correspond.

- The idea that literary genres change through time, and are the product of particular social and historical processes.

In this book, the authors will be referring to both of these trends, but we believe that it is only of limited use to classify a given text without also considering the process by which it came into being. For us, literary genres are not timeless essences, but emerge through the circulation of ideas and practices within a specific culture. Taking into account genre is one important way of thinking about the meaning and interest of literary texts.

The genre we consider here is realist prose fiction, which may be said to have become the dominant literary form in Europe in the first half of the nineteenth century. The examples chosen to focus on all come from that place and time, and have been carefully selected to demonstrate just how helpful it can be to read them in terms of their defining features. Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice (1813) and Charles Dickens’s Great Expectations (1860–1) are well-known, ‘classic’ examples of realist prose fiction; Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818) offers a challenge to what may appear to define the form; and Ivan Turgenev’s Fathers and Sons (1862) shows how far the realist ‘aesthetic’ or artistic approach became the dominant mode beyond the merely English employment of its conventions. The point of examining these texts closely is to ensure that our generalizations are always well grounded. Far too much of the study of literature nowadays has moved onto a plane that excludes the works themselves, in all their complexity and seductive particularity.

Rules and expectations

First, as you may already have protested, who apart from professional critics and other specialists classifies literary texts? The immediate answer is that most, if not all, of us do on some level, and for good reason too.

To allow me to prove this to you, please try the following exercise. What kind of literature would you say the passage below belongs to?

The bodies were discovered at eight forty-five on the morning of Wednesday 18 September by Miss Emily Wharton, a 65-year-old spinster of the parish of St Matthew’s in Paddington, London, and Darren Wilkes, aged 10, of no particular parish as far as he knew or cared. This unlikely pair of companions had left Miss Wharton’s flat in Crowhurst Gardens just before half past eight to walk the half-mile stretch of the Grand Union Canal to St Matthew’s church. Here Miss Wharton, as was her custom each Wednesday and Friday, would weed out the dead flowers from the vase in front of the statue of the Virgin, scrape the wax and candle stubs from the brass holders, dust the two rows of chairs in the Lady Chapel, which would be adequate for the small congregation expected at that morning’s early Mass, and make everything ready for the arrival at nine twenty of Father Barnes.

Discussion

If you guessed that this extract is from a detective novel, you were right. You might also have said ‘crime novel’ or ‘mystery novel’, with which it shares many features, although if you had been able to read on to the start of the next chapter, you would have had ‘detective novel’ confirmed: ‘As soon as he had left the Commissioner’s office and was back in his own room Commander Adam Dalgliesh rang Chief Inspector John Massingham.’ The passage is, in fact, the opening paragraph of A Taste for Death (1986) by the well-known writer of detective fiction, P.D.James. Detective novels are one of the most popular kinds or genres of literature that you are likely to encounter today, and it is precisely (although not exclusively) the features that are indispensable to the genre that have made it so popular. Readers know what to expect and want more of what they read. ■

Indispensable to the detective genre are such features as: a crime, usually murder; a plausible setting, including a detailed and specific account of time and place; and, of course, a detective, often a professional, who has special intuitive and/or deductive powers. Did you perhaps notice that the passage begins like an official report—‘Miss Emily Wharton, a 65-year-old spinster of the parish of St Matthew’s in Paddington, London’—and then makes a joke of this, with ‘Darren Wilkes…of no particular parish as far as he knew or cared’? This sort of playfulness is characteristic of the writing of P.D.James, and is more common to English than American detective novels. It is not necessary to the genre; it is a variation that adds to its appeal. Many English detective novels also have a religious setting—aptly enough, since they deal with death and the defeat of evil. An even more common feature is suggested by the ‘unlikely pair of companions’, Emily Wharton and Darren Wilkes: the crime and its resolution tend to bring into contact people from widely different classes or areas of society.

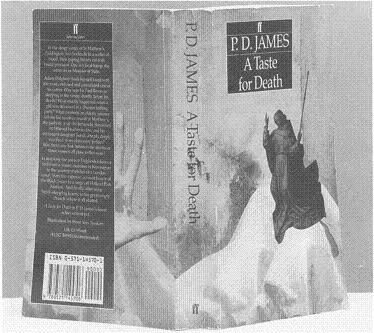

Of course, if you had first picked up the book in question, the cover and format would have told you what kind of literature to expect. The cover (Figure 1) depicts a little statue of a monk or saint floating above a bloodstained sheet over what appears to be a body, and the ‘blurb’ on the back offers a summary of the plot without giving away ‘whodunit’. You might have found it in the ‘detective fiction’ or ‘crime’ section of a library or bookshop, while looking for an enticing title by an author you had heard of, or seen reviewed. The cover, the ‘blurb’, the library or bookshop classification are all what are known as cultural indicators of the book’s genre. Nevertheless, it is important to realize that there are also clues in the way a book is written that suggest the genre to expect.

Why is this important? On one level, it does not seem to matter at all and on another, it matters a lot. It does not seem to matter because reading is so much a private, unreflecting process, especially reading a story of this kind, which we are likely to want to read fairly fast in order to find out what happens next. This already begins to show why it does matter that we ‘know’ what kind of text we are dealing with. (I have placed the word ‘know’ in quotes, because I do not mean to say that we can fully articulate what it is that we know in this case.) It matters because we would not want to read any further if we did not expect to discover who has been killed, how they were killed, why they are in the church, what the connection is between the 65-year-old spinster and the boy, and so on.

We read literary works with certain expectations, and it is a crucial part of the reason we read, and the pleasure we obtain, that those expectations are satisfied. The detective novel demonstrates this fact very clearly, because it is a relatively strict literary genre. By strict I mean that it can be seen to have clear and definable rules. Some of the most famous practitioners have themselves defined these rules. The American writer Raymond Chandler, creator of the private detective Philip Marlowe, listed ‘ten commandments for the detective novel’ as follows.

- It must be credibly motivated, both as to the original situation and the dénouement.

- It must be technically sound as to the methods of murder and detection.

- It must be realistic in character, setting, and atmosphere. It must be about real people in a real world.

- It must have a sound story value apart from the mystery element; i.e., the investigation itself must be an adventure worth reading.

- It must have enough essential simplicity to be explained easily when the time comes.

- It must baffle a reasonably intelligent reader.

- The solution must seem inevitable once revealed.

- It must not try to do everything at once. If it is a puzzle story operating in a rather cool, reasonable atmosphere, it cannot also be a violent adventure or passionate romance.

- It must punish the criminal in one way or another, not necessarily by operation of the law…if the detective fails to resolve the consequences of the crime, the story is an unresolved chord and leaves irritation behind it.

- It must be honest with the reader.

(Quoted in Parsons, The Book of Literary Lists, 1986, p.129)

Figure 1 Cover designed by Irene Von Treskow for the paperback edition of P.D.James, A Taste for Death, 1986 Reproduced by permission of Faber & Faber Ltd.

It is typical of the stricter literary genres (the sonnet is another) that they involve rules like this, which describe, or even prescribe, how they should be written. If you have read detective novels, you should be able to confirm that these are some of the essential ingredients. Indeed, you should be able to do so even if you have not read any such novels, but have seen film or television detective stories, such as Farewell, My Lovely (1975), based on Chandler’s novel (1940) of the same name, or the television versions of P.D.James’s novels.

Another way of expressing this is to say that we are familiar with the ‘tradition’ of the detective story. Like every genre, the detective novel has its own literary tradition, which has emerged over time. According to Nicholas Parsons, P.D.James’s choice of the ‘six greatest masters or mistresses of the detective genre’ is Wilkie Collins, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Dashiell Hammett, Agatha Christie, Dorothy L.Sayers and Margery Allingham, whose works span the nineteenth and twentieth centuries (ibid., pp.48–9). Each of us may have a different list. I would have mentioned Dickens, whose Inspector Bucket in Bleak House (1853) has to solve two murders, and who appears earlier than Wilkie Collins’s Sergeant Cuff, in The Moonstone (1868), although not before Edgar Allan Poe’s Auguste Dupin, in ‘The murders in the Rue Morgue’ (1841), probably the first modern detective story. Whether or not you are familiar with any of these works, you can read and enjoy P.D.James insofar as the expectations set up by her novels meet to a sufficient degree your own personal experience (including reading books and watching television) and attitudes. It will enrich your reading to read other examples of the genre, and if you were going to study the detective novel, you would have to read other examples in order to understand better what they set out to do, and how far they seem to you to achieve their ends.

I would like to turn again to Chandler’s ‘ten commandments’. Which are the most important elements for the reader of the detective novel? Are there elements that are important for novels in general?

Discussion

Chandler’s rules operate on two levels. First, there are the specific elements that seem important for the form of detective novels, that is, the crime-puzzle-solution elements. Secondly, there are the more general elements: credibility, being ‘realistic in character, setting, and atmosphere’, and having a ‘sound story value’. The emphasis upon uniformity, keeping to the rules of this genre and not straying into another, is itself typical of the detective novel, as I have already suggested. Overall, what strikes me as most important is Chandler’s stress upon the writer’s relationship with the reader.

This is really the key to the whole question of defining the genre of a literary work. It could be argued that we know what detective novels do, even if we have never read one, because they draw upon assumptions and expectations we have built up over a long time, going back to when we first learned to read, indeed learned our language. It is not by coming across all the possible uses of the language that we become fluent speakers of it, but by incorporating (nobody is quite sure how) its rules, as a result of experiencing a certain, limited amount of it. It is the same with the ‘languages’ of literary forms: on the basis of a certain experience of, say, novels, we learn what to expect when we pick up a particular book described as a novel. Just as being a fluent speaker of English does not mean being fluent in all the (geographically and historically) different varieties of English that exist, so being an experienced reader does not mean knowing all the different varieties of reading that exist. What we do, when encountering a new or unfamiliar variety of language use, is try to relate it to what we already know. The same process of ‘normalizing’, or ‘recuperation’ as it is sometimes called, applies to reading texts. The excitem...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- Part One

- Part Two

- Bibliography