1

Speaking up in a public space

The strange case of Rachel Whiteread’s House

Introduction

Competing theories of social interaction have privileged either its textual aspects or its nature as practice (recent theories of “media events” being a hybrid case). But how do we understand what happens when multiple textual and other practices confront each other in a public space that is also a site in media narratives? What gives rise, suddenly, to the “sense of an event”? When media space and public space overlap, the answers must lie beyond media-centred theories – but where? These questions, not readily answered yet, are fundamental to an account of the media’s role in society. Recent practice in public art offers an important and insufficiently studied means of approaching these questions. This chapter seeks to open up this territory by examining the controversy that raged around House, a public sculpture displayed in London’s East End, late in 1993.

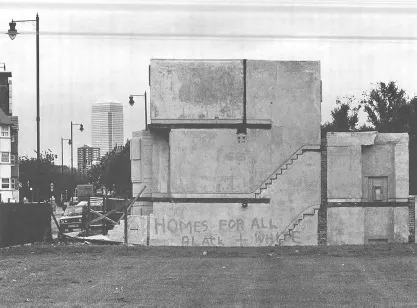

Rachel Whiteread’s House was in Bow: the concrete cast of a house’s inside, left exposed when the last of a Victorian terrace was demolished to extend parkland. House was also an event – or rather, many events (private and public), focused, through the media, on the sculpture, its reception, and ultimate demolition. I attempt to make sense of those events.

I am not trying to expound House’s meaning nor to judge its value as art. By “making sense”, I intend more the unravelling of the different processes which generated meanings in relation to House. A broad canvas is necessary, stretching beyond art discourse. Here, Sharon Zukin’s work is exemplary – especially her book-length study of the New York loft scene.1 Zukin’s insistence on grasping the loft scene as “a space, a symbol, and a site under contention by major social forces” remains an essential guide.2 Her analysis, however, tends to reduce the intentions and messages of artists to underlying social patterns of appropriation. This closes off a possibility which I will leave open: that art itself is a strand in debates about those very social conditions.

Another broad context of this chapter is the continuing debate on the public sphere which has evolved from Habermas’ original critique of liberal models to a notion of the public sphere as one or more spaces in which identities and values are developed in a process of “discursive will formation”.3 In its wake has come fascinating work on the “new social movements”, which have recently developed in the face of the “information society”.4 These movements, while largely submerged in civil society, are capable of “temporary mobilisations” in the public sphere.5 Their mode of action fuses “public and private roles … instrumental and expressive behaviour”.6 Indeed, through “the defining power of media publicity”, the media emerges as a central “site” for this new “sub-politics”.7 This is useful background for understanding House (with its strange alchemy of public and private space, its structure as media event, and latent political content).

There is, however, little specific precedent for investigating a work such as House. Dick Hebdige’s recent pioneering study of Krystof Wodiczko’s Homeless Vehicle Project is therefore this chapter’s third and indispensable context.8 Hebdige, through an impassioned analysis of how Wodiczko’s work addresses its viewers, develops the important notion of “witnessing” as a form of social awareness. A weakness is that Hebdige conceives “witnessing” entirely within the frame of the act of reading the artwork itself. In a typical passage, he comments: “What makes it so difficult to dismiss this project out of hand is the challenge it issues to all those who enter into dialogue with it to improve upon Wodiczko’s own ‘modest proposals’ ‘to help the homeless’ ”.9 The qualification is crucial. For it is precisely behind the cover of that qualification that we must investigate: who enters into dialogue, how, in what context, and on whose terms?

Figure 1.1 Rachel Whiteread’s House seen against the background of London’s Docklands

A certain scepticism is necessary. Like Baudrillard, we should question whether a work of art “speaks to us” directly, let alone “confronts reality”.10 I aim to be less a “witness” of what House “revealed”, still less an explicator of the work’s “inside”, more an investigator of its outside(s), conceiving art, like the book in Deleuze and Guattari’s formulation, to “exist only through the outside and on the outside”, the outside(s), that is, of public space and the public sphere themselves.11

Background

Like most houses in Bow, 193 Grove Road, the site or rather frame of House, was terraced.

Bow is a “neighbourhood” of Tower Hamlets (an administrative division of the Borough introduced in the 1980s). Tower Hamlets (due east of London’s financial centre, “The City” and having as its southernmost region Docklands, where a new business centre famously failed in the 1980s) is one of London’s poorest boroughs, with high unemployment and severe housing problems. Bow is not one of the poorest neighbourhoods but shares many of Tower Hamlets’ general characteristics: 57 per cent of its housing is council provided, less than one per cent. is detached or semi-detached and almost 60 per cent. of its households lack a car.12

Housing is a central political issue locally. Claims of “bias” in favour of ethnic minorities in the Council home waiting list characterised the campaign of a British National Party candidate elected in Docklands in September 1993. Nor is the public environment a neutral issue: the extension of the park which required 193 Grove Road’s demolition conformed to a general Council policy of improving the look of the area: “old-style” lampposts, ornamental park gates, plaques marking the “Bow Heritage Trail”. Some councillors hoped a bold, new public sculpture would benefit the neighbourhood’s image.

What was the background to the artistic conception of House? The history of art in public spaces is complex, but two points are crucial. First, in the 20th century, many ideas influenced public art apart from its long-term antecedents in monuments and architecture: the search for art’s wider public function; increasing dissatisfaction with the limitations of the painting frame and gallery space; and a critique through artistic intervention of conventions of public space and architecture.13

Secondly, a break in this history occurred in the late 1970s and early 1980s when new questions about how art interacts with its public became central. Many factors came together: feminist critiques of art institutions, Joseph Beuys’ notion of “social sculpture”, the practice of art in community programmes, critiques of the implication of earlier public art with corporate interests. This new public art emphasised not just process but the particular active process of making art with the public. It could envisage public art as a discursive space, “a community meeting place” (Vito Acconci).14 It often favoured public sculpture, which avoided claims to permanence, yet was politically engaged.15

House was intended as temporary and to have relevance to issues of local significance. It belongs therefore to this new phase of public art.

The sequence of events

Early in 1993, Artangel (who commissioned House) agreed with Bow Neighbourhood to sign a temporary lease of 193 Grove Road after researching widely for a suitable location for Rachel Whiteread’s projected piece. Substantial audiences and media coverage for House were expected; the proposal was endorsed by prominent art bodies and sponsored by Beck’s Beer.

Delays in starting the casting process meant the sculpture was not unveiled until 25 October (leaving less time than planned for viewing before the lease expired at the end of November). Sidney Gale, the house’s occupant, was rehoused by the Council over the summer. After the opening, there was an explosion of praise from the national broadsheets. Opposition to the sculpture (from local people and critics) was already newsworthy.16 Soon people were reported as travelling long distances to see House.17

A crucial factor in this public and media interest was the context of the Turner Prize, given annually by the Tate Gallery to a young British artist for an outstanding exhibition in the last 12 months. The prize’s alleged “bias” toward “neoconceptual art” had been controversial for years, but with Whiteread as one of the four prize nominees, House became a principal focus of attention in the often-hostile coverage of the Prize. Interest was intensified by the K Foundation (a front of the former pop group the KLF), who advertised an award of double the Turner Prize money for the “worst” artist, to be nominated by the public from the Turner nominees.

On Tuesday, 23 November, the Turner Prizegiving was to be televised live on Channel 4. The K Foundation had booked an advertising slot in the programme to announce the result of their counter-prize. Earlier that evening, a Councillors’ meeting to consider Artangel’s request for extension of the lease (already publicly rejected by Eric Flounders, Bow Neighbourhood’s Chair) was scheduled.

Within a few hours, Whiteread was awarded the Turner Prize and the K Foundation’s prize (in the form of almost £40,000 in cash nailed to a frame and chained to the Tate Gallery’s railings) and the Neighbourhood (on a split vote) rejected extension. Debate about House intensified. The Neighbourhood received more than a hundred letters overwhelmingly supporting extension, the Bow Neighbourhood Forum voted similarly, and the local Labour MP obtained House of Commons support to put down a motion calling for a local referendum on House’s life. The next weekend, the surrounding parkland was full of people viewing, arguing, and being lobbied by different sides. Substantial petitions for and against House’s removal were collected.

Delays in arranging demolition ensured that House survived beyond 30 November, the reprieve becoming official when “benefactors” including Channel 4 and Beck’s paid to extend the lease until the New Year.

By the eventual demolition on 11 January 1994, Artangel claimed 100,000 visitors to the site. Demolition occurred in front of television cameras, Rachel Whiteread and Sidney Gale looking on. By then, the press had already billed the episode as an example of “the eternal struggle between art and authority”, a dispute “In the House of the Philistines”, or “one of the most enjoyable cultural squabbles for years”.18

Media coverage

UK media attention was extensive: 20 reviews, 3 editorials, almost 50 news and comment items, 32 items in letter columns and more than 10 cartoons and other humorous references. There was regular coverage in the East London Advertiser and, at key points, coverage in many regional newspapers across Britain. There was also considerable interest in weekly magazines in addition to television and the international press coverage.

The storyline House emerged against the background of well-established storylines about modern art and the “follies” of the Turner Prize in particular. In addition, House quickly became a convenient reference point for other issues: the standing of a controversial critic who opposed House (Brian Sewell), the adequacy of government arts funding and the value of business sponsorship.

Clear patterns emerge. There was universal and exceptional acclaim for House from the arts correspondents in the broadsheets. House was typically read as some kind of statement: for example, “a stark comment on social realities” or “as commemorating a century of domestic life even as it insists on the impossibility of recovering the lost lives spent within it”.19 As the controversy heightened, positions became increasingly rhetorical, with calls (more appropriate to debates on earlier permanent public art) for House to be preserved.20

Hostility to House took three forms: (i) reviews by arts correspondents of some conservative tabloids; (ii) comments by non-art columnists in both those tab...