- 384 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This incisive inter-disciplinary text provides a major contribution to the study of finance capital and the metropolis. It is the first authoritative account of the momentous changes in the organisation of finance capital that occurred in the 1980s. But it never contents itself with a mere record of events. Changes in finance are scrupulously and consistently related to changes in urban forms, notably metropolitan lifestyles and aesthetics.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Global Finance and Urban Living by Leslie Budd,Sam Whimster in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

GROWTH AND DYNAMICS OF FINANCIAL MARKETS

1

LONDON’S FINANCIAL MARKETS

Perspectives and prospects

In the summer of 1986 the City of London was an exciting place, where there was a very special feeling of newness, of adventure, of setting out into unknown territories. Opportunities were there to be seized and risks to be taken. The world seemed to be divided into those who possessed the knowledge, courage or sheer cheek to take the opportunities and to accept the risks and the others who were merely competent, diligent and dull. Energy and daring often seemed quite as important as financial expertise although that quality was present, too. A senior manager in a most respected British merchant bank told the writer that it was traders, barrow boys, that were needed, but he hired graduates. At another firm, where broker-dealers had been absorbed into a financial conglomerate, a distinguised senior partner from the former broking house expressed concern at the problem of dealer burn-out The City had become powerful, cruel and aware of the need to adapt and compete. Often, though, it did not fully understand the processes which were at work; it is learning to do so.

Financial markets absorb and respond to information but the most vital information concerns conjectures about the essentially unknowable future. Technically, financial markets are about responses to uncertainty. They are also about economic and political power. It is only by taking a view of the processes of change and the way in which they have evolved that the likelihood of future directions can be assessed.

THE PROCESS OF CHANGE

The deregulation of the London Stock Exchange, now known as the International Stock Exchange,1 was a late response to a process of internationalisation in financial markets which had been growing in power and force for a quarter of a century. In those years, City firms experienced a growing involvement with foreign banking houses, with international lending and with overseas securities markets. The traditional City had an unrivalled ability in the techniques of international banking and the finance of foreign trade. It also had a sound commercial infrastructure: competent and experienced accountancy firms, corporate and financial lawyers, excellent business communications and a reputation for probity. The City was, and is, well-positioned in relation to the international time-zones. In spite of these advantages, the City of the 1960s and 70s tended to be slow to react to change. Its institutions and markets were constrained by convention, by restrictive practices and, to an extent, by legislation. The calm and stability of this highly intelligent but essentially complacent world was upset by the arrival of an increasing number of enterprising and aggressively competitive overseas banks. These overseas, and particularly American, banks were attracted to London partly by the freedom from regulation enjoyed by foreign financial firms in the United Kingdom and partly by London’s advantages as a centre for the growing and profitable eurodollar markets. Neither the presence of foreign banks nor operations based on eurodeposits could, of themselves, have changed the ethos, institutions and practices of the City of London but both factors were greatly reinforced during the 1970s in ways that positioned London financial firms precisely to take advantage of the next decade’s even more significant developments.

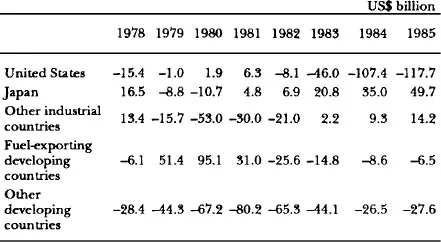

The growth of dollar deposits not located in the United States and of wholesale lending based on these funds was given impetus by the current account imbalances which emerged between major groups of countries in the world economy. Current account imbalances have, in the nature of things, capital claims and the transfer of financial assets as their counterparts. These give rise to international financial pressures which, because they have their origins in fundamental economic conditions, develop great power. The oil price rise of 1973 generated massive surpluses for the oil producers and threw importing countries into deficit. London was well-prepared to accept this OPEC business which, politically, could not go to the United States. With oil contracts denominated in dollars, however, the effect was to give a further, massive boost to the London eurodollar markets. The flow of dollar funds into London was lent-on to developing countries notably in Latin America but also to borrowers in Africa and to Poland. Dollar lending outside the USA was not constrained by reserve requirements and consequently the international flows were amplified by the eurodollar multiplier effect.2

The net size of the eurocurrency markets, which to some extent involved other currencies than dollars, grew from US$11 billion in 1965 to US$661 billion by 1981. Eurodollar lending looked very profitable to the international banking community; the rates charged to borrowers were linked to LIBOR (the London Interbank Offer Rate) and the risks seemed small since the borrowers were usually the governments of sovereign states. Moreover, with interest rate risk reduced by linking the rates charged to borrowers to LIBOR and country risk compensated for by the size of the spread (with less credit-worthy borrowers paying higher rates) and reduced by diversification, eurocurrency lending seemed to make very good sense. Syndicating the loans over a large number of banks enabled the international banking system to handle the enormous sums which were coming onto the market and to achieve the aim of distributing risks widely. The ability to manipulate funds on such a scale, to assess the risks, to assemble the syndicates, some of which involved the cooperation and commitment of scores of banking houses, and to devise appropriate financial mechanisms required great ingenuity in terms of procedures, communications and funds transmission.

London’s experience as the centre of eurodollar lending enhanced its banking skills, widened its network of international relationships and gave a new boost to the already impressive rate of technological change in the electronic transmission of funds. At the end of the 1970s the financial kaleidoscope was given a further shake by the second oil price quantum-rise of 1979. This brought the oil exporting countries, who had been drifting into deficit, back into surplus. But in the succeeding years the supply side of the market for crude oil responded to higher prices and the surplus had disappeared by 1982. In the meantime, though, another equally significant factor had become apparent. This was the growth of Japanese trading and manufacturing strength which with its counterpart, the United States deficit, set the scene for much of the decade which followed and provided the thrust for the changes which swept through the financial world.

The pattern of current account balances which developed is shown in Table 1.1.

Behind the trends exhibited by the figures lay not only Japanese economic efficiency and vigour, but also the United States’ combination of tight monetary policy with a loose fiscal stance. This was a product of the pressures on the US government and the independent attempts by the Federal Reserve Bank to counter the inflationary consequences of government policy. The results were the dual deficits—budgetary and payments—and a tendency towards higher interest rates that inevitably spilled over to other Western economies.

Table 1.1 Current account balances, 1978 to 1985

Japan’s economy was characterised not only by a determined efficiency in the exporting industries but by a very high savings ratio, that is the ratio of saving to income. Japan, therefore, produced a flow of funds seeking opportunities for investment while America had an urgent need to finance her deficit. With Japanese funds playing a more important and sometimes a dominant role in financial markets, the outlines of the modern system began to emerge. The United States was not alone in pursuing more stringent monetary policies; monetarism was the fashion in many western economies and in consequence inflationary pressures diminished. With interest rates tending to rise but inflation diminishing, real interest rates rose. One estimate (Cline 1983) is that average real interest rates, that is nominal rates less the rate of inflation, stood at a negative figure of −0.8 per cent during the 1970s but that the real rate had risen to 7.5 per cent by 1981 and to 11 per cent by 1982. The negative rates had made borrowing attractive for the developing countries in the earlier period but the strongly positive rates of the early 1980s made their position untenable, with large debtors seeking rescheduling or threatening default London banks moved away from syndicated eurodollar loans which now seemed decidedly fragile. In their place they were able to apply their knowledge, experience and financial resources to the issuing of medium term notes and bonds. By 1984, the value of eurobond issues, that is of bonds denominated in currencies other than those of the countries in which they were sold, equalled that of eurodeposit loans with new business in both markets running at £100 billion a year. Soon, syndicated loan business was confined to renewals and reschedulings.

The shift in the balance of activity altered the relative influence of investment and commercial banks in the euromarkets and prompted fresh innovations in the design of the financial instruments employed. It also brought large corporate borrowers into the euromarkets and so opened up new and very large sources of finance to industrial and commercial companies in the major economies.

With the emergence of the eurobond markets, the pace of financial change accelerated. The influx of American banks into London increased as United States banks, and particularly New York banks, prohibited from combining investment and deposit banking in the States and facing further problems as a result of legislation in 1980 and 1982, established investment banking subsidiaries in the City.3 It would have been surprising if the flow of Japanese capital coming into London and New York had not induced Japanese investment banks to follow. The trigger for full Japanese participation in the financial markets was probably the Yen-Dollar agreement of the summer of 1984. With the liberalisation of currency flows coinciding with the substantial Japanese trade surpluses, banking flows between the three major centres—New York, London and Tokyo—were bound to increase still further. The high savings ratio was a domestic feature of long standing in Japan and Japanese banking groups, rigidly defined by their functions in their home markets, were able to deploy capital resources which were much greater than those available to British clearing banks. In the almost unregulated freedom of the international capital markets, they were able to apply their financial muscle with flexibility, determination and an impressive clarity of intention.

By 1985 there were over four hundred foreign banks with major presences in London. These included not only American and Japanese, but also European, banks as continental Europe grew in prosperity. Competition from aggressive and innovative American and Japanese investment banks introduced a briskness of style and pace which induced British financial firms not merely to accept but to embrace with enthusiasm the changes which were taking place around them. The changes were structural, technological and institutional. They were responses to the forces generated by the disequilibria discussed above and together they amounted to the globalisation of financial markets.

The term ‘globalisation’ implies more than that financial markets were international; the suggestion is that delays in time and defects in information across the globe had diminished to the extent that trading was not significantly fragmented. For most markets, trading could produce a common price and for most financial products arbitrage was possible across the markets. Behind the global financial markets was the technology of globalisation: the technology of financial innovation and the technology of information and communication. When there were defects of information or delays in transacting, opportunities for profit tended to induce new practices and innovations. Technological developments made increased financial innovation possible but they also made it more necessary, so that a strong element of positive feedback was introduced into the process with the number of financial innovations increasing year by year. One respected observer recorded thirty-seven major innovations in 1985 alone (Kaufman 1986).

The use of computers and advanced information technology for transmitting, categorising and analysing market information was most developed in foreign exchange (FOREX) trading but it was closely paralleled in the bond and securities markets. The products devised and traded, as Nicholas Robinson describes in Chapter 3, crossed the conventional boundaries of these markets. With the increased volatility which followed more rapid trading and faster response to information as well as with the greater sums in play, there was an acute need to control exchange rate and interest rate risks. This applied not only to banks and financial firms but also to major trading and manufacturing companies, who were becoming increasingly aware of the necessity of managing their treasuries skilfully and profitably. Markets were technically more complex than they had ever been. They absorbed and transmitted vast funds and they were becoming interrelated with major transactions involving foreign exchange markets, bond markets and securities markets in a single deal.

In this situation the complementarities between the traditional City and the more forceful newcomers were apparent in terms of functions, since investment bankers needed access to the Stock Exchange, but the changes required were considerable and were at first resisted. Stock Exchange firms were undercapitalised and single capacity, the separation of agency broking from jobbing (market making) was the rule, and minimum commissions were fixed. The US commercial banks, Japanese banks and major British financial houses needed organisations of greater financial size to operate effectively in the new financial markets; they needed to trade in bonds, securities and currencies as well as offering financial services. There was a need for new, large multifunctional financial institutions. One way or another the financial tides released by the events and trends described would have transformed the institutions and practices of the City of London. Had the Stock Exchange not admitted outside financial firms after the Parkinson—Goodison accord of 1983, first to a limited extent and after March 1986 with full ownership, then other ways would have been found to conduct a London trade in UK and foreign equities and gilts, perhaps through NASDAQ4 or some alternative and specially devised electronic market No doubt there would have been defensive legal manoeuvres to delay this, but every attempt to evade the invasive consequences of the forces in play would have confirmed London’s status as an inward-looking, restrictive and declining financial backwater. There is no doubt that, before the injection of new money by the emerging financial conglomerates and the deregulation of October 1986, the London securities market was an exp...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- List of contributors

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Part I: Growth and dynamics of financial markets

- Part II: Patterns of culture, space and work

- Name index

- Subject index