![]()

1

Dorothea Lange and Turn-of-the-Century America, 1895–1912

Dorothea Lange had two childhoods. The first childhood was a sheltered one, with two parents, in a seemingly loving household. Her family circle included a younger brother, a grandmother, aunts, and uncles. She enjoyed school, and her parents introduced her to theater and music. Her second childhood was one of loss. Polio disabled her when she was seven; five years later, her father abandoned the family. Her mother struggled as a single parent to raise her children. Lange became unanchored. Out of these two childhoods Lange made herself.

Lange’s first years resembled the lives of many middle-class girls at the turn of the century. Lange was second-generation American, her parents both children of German immigrants who had arrived around the time of the Civil War. They lived in Hoboken, New Jersey, across the Hudson River from New York City. In the 1890s when Lange was born, the U.S. brimmed with immigrants. In major cities such as Boston, Chicago, and New York, four out of five people had at least one foreign-born parent, but in the inhospitable plains of Nebraska or Minnesota, and in small mill and mining towns, immigrants were a substantial, sometimes predominant presence. Unlike many immigrant children, however, Lange’s early years were comfortable, even privileged.1

Lange’s maternal family had arrived in steerage, which guaranteed a berth, but not food for the transatlantic journey. They remained shamed by their lowly circumstances, but were soon conveyed to economic stability and middle-class status through their trades. Lange’s paternal grandparents, the Nutzhorns, were grocers and property owners. Lange’s paternal grandfather was a man of substance who sat on local church and trade boards. Because Hoboken was the terminus for German shipping lines, the majority of residents shared her family’s ethnicity.

Lange’s parents met in this thriving immigrant city, and their lives prospered in tandem with it. Lange’s mother, Johanna (Joan), had a lovely voice and sang soprano in a church choir well enough to command payment for her services. Before her marriage Joan Lange worked as a library clerk, suggesting a degree of independence for a woman of that era. Lange’s father, Heinrich (Henry) Nutzhorn, attended a liberal arts college in Wisconsin at a time when just one percent of the population received a college education. He soon practiced the law, and was admitted to the New Jersey bar at twenty-three years of age.2 Joan and Henry married in 1894, and Dorothea Margaretta Nutzhorn was born one year later. The Nutzhorns lived in a fine brownstone. Soon after Lange’s birth, the family moved to nearby Weehawken. Perched on the Hudson River Palisades, Weehawken provided panoramic views of Manhattan, the nation’s metropolis. Lange’s mother quit her job to care for her daughter and maintain their home, though the family also enjoyed a maid. In 1901 Lange’s brother, Henry Martin, or Martin as he would be called, was born. Six years his senior, Lange identified as her brother’s keeper throughout her life.

Despite her immigrant roots, Lange perceived herself as American. During her childhood, many leading figures recoiled at the new immigrants surrounding them, believing them a threat to their Anglo-American nation. Novelist Henry James visited Ellis Island and left shaken at having to share his “American consciousness and patriotism” with the “inconceivable aliens” he saw there. Many Americans gave credence to ideas of race and racial hierarchy, which appeared natural to them. The “white race” was divided into higher and lower orders. Anglo-Saxons from Great Britain or Germany such as the Langes sat at the top of such hierarchies. Southern Europeans, Italians and Greeks, and the Jews and Slavs of Eastern Europe, who emigrated in great numbers at the turn of the century, were decidedly lower. Such racial and ethnic thinking saturated public culture. Writing for the middle-class readership of the journal Century, a top political economist stated, “Slavs are immune to certain kinds of dirt. They can stand what would kill a white man.” Businessmen shared tips on “Americanizing” their immigrant workforce by teaching them how to chew food and brush their teeth. Even Progressive President Theodore Roosevelt implored native white women to bear children to protect “Old Stock” Anglo Americans. Women’s refusal would result in “race suicide.”3 As an adult, Lange fought for an egalitarian nation that rejected racism, but she retained a belief in ethnic difference.

Immigrants, whether privileged like Lange’s family, or desperately seeking new prospects like so many others, were drawn to the U.S. because of its economy, which flourished after the Civil War. Mammoth industries, such as steel and oil, made the nation an economic powerhouse. Other industries grew apace. Southern blacks and Eastern European immigrants filled jobs in Chicago’s meatpacking industry; Italians quarried granite in the hills of Vermont; Welsh and Scots pulled coal from the earth in Illinois and Pennsylvania; Irish and Greeks mined in Montana and Colorado; and Europeans and South and East Asians worked the West Coast canning industries. Across the river from Lange’s home, in nearby New York City, the garment trades were well established by 1900, along with other light industry such as umbrella manufacturing, food production, and publishing. Hoboken boasted shipbuilding as its primary industry, but there were also makers of wooden pencils and Hostess baked goods. Jobs were plentiful in this industrial economy, though employment was insecure; layoffs were frequent, wages grossly inadequate, and accidents common.

Industrial expansion fed urban growth in Lange’s Hoboken and nationally. In a twenty-year period surrounding Lange’s birth, from 1889 to 1909, Hoboken’s population of manufacturing workers tripled. In a circular process, cities and their growing populations further developed the local and national economy. Five years before Lange was born, about one-third of the nation’s population lived in cities, the other two-thirds in rural areas. Five years after her birth, in 1900, two out of five lived in cities, and in 1920, by the time she was a young adult, the nation had become a nation of towns and cities rather than farms. Joining immigrants, such as the Langes and Nutzhorns, were native-born Americans, who fled farms and rural towns for urban opportunities.4

Urban growth made American cities combustible. Cities lacked the complex structures of governance required to meet the needs of exploding populations. Public health programs, municipal sanitation, and welfare support for the poor, the disabled, and the unemployed were limited. There was not enough housing, and growing tenement districts repelled middle class and elites, who feared to enter them. Political corruption was endemic, a reality best encapsulated by one New York City official who described his own graft as “I seen my opportunities and I took ’em.”5

Lange’s father entered this tumult. He was ambitious, and served as a “freeholder” or Hudson County board member. At twenty-seven, he was elected a Republican representative to New Jersey’s state legislature. He ran as a Progressive, fighting the excesses of unregulated capitalism and urban political “machines” that managed, often for their own benefit, industrialism’s turbulence.

The Nutzhorns’ class status cushioned Lange; her early childhood seemed tranquil. Her parents cared for her material well-being, and her extended family indulged her youthful interests. While immigrant urbanites were building a whole new commercial culture of dance halls, vaudeville, amusement parks, and nickelodeons, the Nutzhorns immersed themselves in a classical “high culture.” On both sides of the Atlantic, elite and bourgeois Americans and Europeans enjoyed operas by Verdi, symphonies by Mozart and Beethoven, novels by Austen and Tolstoy, and Shakespeare’s poetry and plays. Lange remembers her parents laughing at her youthful attempts to read the bard’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and her father lifting her atop his shoulders to enjoy an outdoor performance of the play. Her mother brought her to classical concerts in fine Manhattan churches, and filled their home with books and music.

Lange’s family also raised her to appreciate craftsmanship. Her maternal great-uncles were lithographers or printers. In interviews as an adult, Lange reminisced about her uncle’s lithographers’ stones; the stones’ purity, she said, spoke to her. Lange also recollected her grandmother, Sophie Lange, a hard woman, who drank too much and had an acid tongue. But her grandmother was a skilled dressmaker, and the wooden table in her home was filled with the pricks made by her pattern cutting wheel. Lange found this beautiful. She admired the table’s utility, which helped bring the wonderful silk garments her grandmother designed into the world. Lange also loved the scarred table, like her uncles’ lithographers’ stones, for its sheer abstract presence. Lange believed her grandmother understood her fixation with beauty long before she herself did. She remembered her grandmother saying, when Lange was only six or seven years old, that she had “line in her head.” Lange thought her grandmother recognized her absorption in “cool, clean,” uncorrupted things. They shared a commitment to that which was “finer,” that which had been worked with attention to detail.

This childhood idyll ended when Lange was seven; her second childhood began. Lange’s parents thought she came down with a cold or the flu. She recovered, then suddenly could not move her legs, and finally became entirely paralyzed. Poliomyelitis (polio) was the culprit. The disease most often hit children, typically with stealth, as it did with Lange. This enteric disease enters through the mouth, breeds in the small intestines, and then attacks the central nervous system, destroying the motor neurons that contract muscles. Before the 1920s, the most unfortunate died, as the diaphragm ceases to maintain lung functioning. In addition to paralysis, polio also causes unbearable pain. When Franklin Delano Roosevelt contracted it in 1921, he could not bear to have the breeze blow over his legs, it hurt so much.6 Immobilization was then the most common treatment. Physicians were unaware that robbing the patient of the use of their working muscles often worsened their condition. Lange was lucky; she regained the use of her limbs. The illness nonetheless marked Lange physically and psychologically. Her right foot became twisted—it was constantly flexed downward and inward and could no longer be lifted, a condition called drop foot. For some period, she wore special shoes with attached metal braces that reached to her upper thighs to keep her from falling. Local children called her “Limpy.” Decades later, her son claimed not to notice her limp, but a friend believed she wore it like her silver bracelets and her beret. Her limp formed part of Lange, but it did not obtrude. Lange complained little, and her vigor astounded others, but polio shaped her self-identity. As she said in an oral history six decades after the disease struck: “[N]o one who hasn’t lived the life of a semi-cripple knows how much that means. I think it was perhaps the most important thing that happened to me, and formed me, guided me, instructed me, helped me and humiliated me… I have never gotten over … the force and power of it.”

Lange’s bout with polio nurtured her independent streak and generated an antipathy toward her mother on whom she was utterly dependent. During the illness’s acute phase, Lange’s mother would have had to meet all of her needs: to feed her, turn her over, help her onto a bedpan, and bathe her. Such dependence would feed despair or even the dislike of her mother that she articulated. Lange later explained that her disdain stemmed from her mother’s insistence that Lange “walk as well as you can” around others. Lange felt diminished by her mother’s obsequiousness around doctors, and thought her mother shamed her to save face.

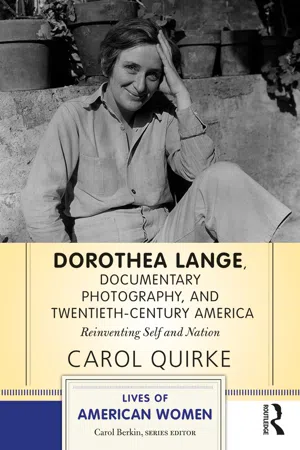

Photos can tell us much, but they can equally veil the truth. A cameo portrait of Lange when she was eight or nine years old shows a girl with her hair pulled back in a large bow, a tight smile, and bright piercing eyes looking directly at the viewer. Her brother stands in front of her, his head canted toward his sister. Both are bedecked in their Sunday best. Martin Nutzhorn wears a suit coat with a sailor collar, and Lange a gathered frock, perhaps of silk or bombazine, with a lace collar. They look contented and cared for; no mark of Lange’s ailment asserts itself. This projected image was rent just a few years later when Henry Nutzhorn abandoned his wife, twelve-year-old daughter, and six-year-old son in 1907. Scholars believe he embezzled his clients’ money, but details are hazy as his crime was never prosecuted. Authorities never found him, as Nutzhorn changed his name and crossed the Hudson and East Rivers, landing in a Brooklyn neighborhood. Desertion was then a crime, so Nutzhorn could have been imprisoned for leaving his family, as well as for financial misdeeds.

Nutzhorn fled when public awareness of what were called “poor man’s divorces” was on the rise.7 Uncommon before the Civil War, the divorce rate nearly doubled in the late nineteenth century. But divorce was expensive. Economic dislocations and greater geographic mobility led those without means to just leave marriages. Desertion became the focus of a whole new field, social work, which developed in part to address growing poverty rates in post-Civil War America. While some economists, social workers, and Progressive reformers believed that laissez-faire capitalism’s low wages, particularly for widows, and unemployment caused poverty, others were convinced that poverty had individual causes, such as male desertion. To control the morally lax, “shiftless” men who refused to support their children, these reformers promoted tough criminal sanctions.

Lange’s family was torn apart by her father’s disappearance just as Lange reached early adolescence, a time when individuals are highly sensitive to social disapproval, in an era when that censure was a matter of intense public discussion. This must have intensified her pain. Further eroding Lange’s equilibrium was her relationship with her mother. Joan Nutzhorn periodically met with her husband for many years. Nutzhorn never told her daughter about her continued connection to Lange’s father until she became an adult, but family silences can communicate as strongly as words. Lange must have sensed an ambiguity, an unspoken reality, which contributed to her sense of her mother’s weakness. Lange only set eyes on her father when she was nineteen. Subsequently, she only saw him episodically, then lost all contact when she was twenty-three years old. This loss was grievous. With loved ones she spoke sparingly of her bout with polio, but she never discussed her father’s abandonment. Her second husband and children did not even know his name.

Nutzhorn’s desertion set off a cascade of consequences for Lange’s family. Evicted from their Weehawken home for non-payment of rent, the family moved to Lange’s grandmother’s home. Her grandmother had an outsized personality, in equal parts “temperamental” and “talented,” and she had begun to drink more. Verbally and physically abusive, her grandmother made Lange a target for her wrath. Lange believed her mother buckled under her grandmother’s will, and she failed to protect her daughter, further corroding relations between mother and daughter. Lange also blamed herself, seeing her younger brother as easygoing and herself as “quarrelsome.” At an age when children assert their independence, the twelve-year-old Lange was plunged into a new environment, with an economically, spatially, and psychologically constricted space.

Lange could not acknowledge her mother’s strengths, but Joan Nutzhorn kept the family together. She found a position as a librarian paying far higher wages than was typical for a woman. Her work lessened the family’s financial dependence on Lange’s grandmother, aunts...