1

THE GAZE REVISITED, OR REVIEWING QUEER VIEWING

Caroline Evans and Lorraine Gamman

INTRODUCTION

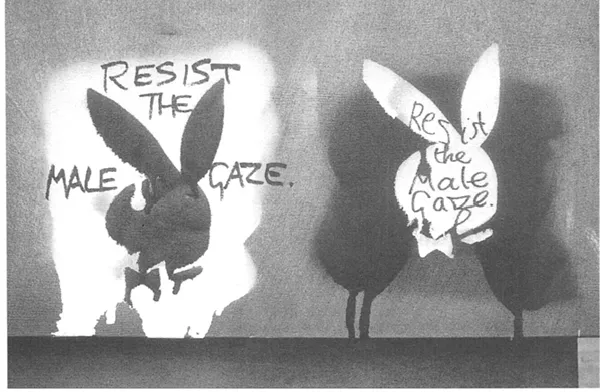

Over the last ten years or so many critical reflections on what has been called ‘the gaze’ have been published and we are not the only writers who have grappled with the complexity of the theory.1 Many debates about the gaze have been dogged by factionalism, theoretical impasse, and a kind of orthodoxy which this article hopes to review and challenge. It is our feeling that many writers have demanded too much of the gaze, and that it has almost become a cliché. Often when individuals use the term the ‘male gaze’ they mean nothing more complex than the way men look at women or, worse, they refer to the male gaze as a metaphor for ‘patriarchy’. For example, in Figure 1, the graffiti slogan ‘resist the male gaze’ is coupled with a playboy motif. We liked the graffiti but we felt the ideas underlying it were a troubling sign of something else. Such usage undermines complex argument and produces crass and essentialist models of social relationships. Primary texts about the gaze were originally much more sophisticated. But even they have proved inadequate as a tool for analysing the complex ways in which individuals look at, and identify with a range of contemporary images, beyond cinema, from art to ads, fashion mags to pop promos.

In this article we want to shift the course of the debate about the gaze by engaging with what Constantine Giannaris has described as ‘genderfuck’.2 By importing some queer notions into the world of critical theory it may be possible to begin to acknowledge many perverse but enjoyable relations of looking. Our reasoning is not only that today’s complex visual iconography requires the sort of theory that can comprehend it, but that previous models of the gaze have produced some very one-dimensional accounts of viewing relations.

This article is therefore written in two sections. The first section reviews gaze theory, including important work which has addressedgay and lesbian spectators, but argues that even this work is flawed by the essentialism of the terms that frame the debate. The second section explains why ‘adding on’ or including the experiences of gay and lesbian spectators is not enough. Instead, we should be problematising the very categories of identity themselves. We go on to locate ideas about queer looks with reference to an anti-essentialist model of gender (and other) identifications.

1 Playboy graffiti (Séan O’Mara)

The first section implicitly draws on the work of two theorists often thought incompatible, Michel Foucault and Jacques Lacan. Instead of making a choice between the two we have opted to act like smash and grab artists and help ourselves to concepts from both. In the second section we have also helped ourselves to the ideas of Roland Barthes. Rather than trying to negotiate a monogamous relationship between Foucault and Lacan, we thought instead a ménage àtrois might be productive and that promiscuous relations, even group sex, with Barthes might show the way forward. It is not that this orgy of theory produces any single cohesive model but that none of the models are adequate on their own. We see the only position to take theoretically is to oscillate between all the theories, to be eclectic and make the best of the recognition that the new grand narratives are no better than the old ones in explaining everything.

GAZE THEORY REVISITED

The gaze: two models, some preliminary observations

‘The gaze’ has been theorised primarily in two ways and to some extent both models deal with questions raised about objectification. First, Michel Foucault has discussed the ‘panopticon’, the perfect prison, where the controlling gaze is used at all times as surveillance. This model posits a relationship between power and knowledge.3 Second, film theorists have used psychoanalysis to formulate a cinematic gaze in terms of gender which functions on the level of representation, rather than in terms of other types of cultural practice.4 Here, film theorists have raised questions about the viewer’s identificatory experiences in relation to what is seen/read. They argue the viewer’s identificatory experiences are constituted exclusively by the visual text in question. One of the things this section tries to do is to challenge this ‘exclusivity’ of definition by the visual text through looking at context (although in the second section we do return to issues about the way texts produce meanings).

Cinematic theories have been applied to many types of visual representation, from high art to popular culture, even though Laura Mulvey’s influential writing on the gaze never claimed to explain more than spectatorship of ‘classic narrative cinema’.5

In this convergence the distinction was lost between cultural activities (such as cruising, cottaging and even market place shopping) which may involve a reciprocal exchange of looks, and cinematic viewing which does not. Most of the theory conceptualises the gaze in relation to representations of people and not inanimate or ‘natural’ things. Hence it is posited as constitutive of social or psychic relations. Neither model (the Foucauldian or the film theorists’) posits the gaze as a mutual one. Of course the cinematic image is an object and therefore cannot look back, so obviously we need to distinguish questions of representation from other cultural practices. But in some writing this distinction has been elided. When individuals cruise each other on the street, or in clubs, the mutual exchange of glances is sexualised and often reciprocal; of course this mutuality is not the case with cinematic viewing.

Our reasons for writing this article stem from mutual discussions about gaze theory and its relevance in teaching critical theory and visual culture to art students. We both found that these ideas about the gaze didn’t help us very much to think about the complex ways images resonate in contemporary culture. This is because when people use the term the ‘male gaze’ they often mean nothing more complex than the way men look at women, and notions about the ubiquitous male gaze often go unquestioned and unspecified.6 Student essays frequently use the term ‘the male gaze’ as shorthand both for the voyeurism implicit in spectatorship (for example, when looking at paintings) and for the idea that women are objectified in Western culture (advertising and porn are often used as examples). It seems as if these ideas about the gaze have entered academic language without students necessarily having read the primary texts which engendered the terms. Also most students seem unable to comprehend from their reading the distinction between looking and gazing. This is not surprising, because the theoretical material on the ‘gaze’ also fails frequently to distinguish between the look (associated with the eye) and the gaze (associated with the phallus). Indeed, there is much conflation in discussion about ‘the look’ and ‘the gaze’. To clarify the differences between the terms, requires a ‘return to Lacan’. Lacan posits the gaze as a transcendental ideal—omniscient and omnipresent —whereas he suggests the eye (and the look) can never achieve this status (although it may aspire to do so).7 Indeed, Carol J.Clover argues that ‘the best the look can hope for is to pass itself off as the gaze, and to judge from film theory’s concern with the “male gaze”…it sometimes succeeds’.8 Elizabeth Grosz has argued:

Many feminists…have conflated the look with the gaze, mistaking a perceptual mode with a mode of desire. When they state baldly that “vision” is male, the look is masculine, or the visual is a phallocentric mode of perception, these feminists confuse a perceptual facility open to both sexes…with sexually coded positions of desire within visual (or any other perceptual) functions…vision is not, cannot be, masculine…rather, certain ways of using vision (for example, to objectify) may confirm and help produce patriarchal power relations.9

One of the reasons students may be confused is because gaze theory is so difficult and it has been applied differently by different academic writers. Therefore we felt it necessary, in the next few sections, to go back and review those texts which have been influential, directly or indirectly, in conceptualising the gaze, starting with the male gaze.

Both in and out of college the phrase ‘the objectifying male gaze’ has become a cliché used to identify the way men look at women, almost as a metaphor of patriarchal relations. Within such clichés there is no space to conceptualise queer relations of looking, or to explain changes in some contexts where women’s experience is not completely defined by patriarchal discourse. Nor is there any space to talk about the implications of a fashion system which encourages women to take pleasure from images of other women, or an advertising system which uses eroticised images of men to sell products to both sexes.

But advertising cannot be construed simply as a ‘determining’ discourse because there is always resistance to consumer marketing. At the time of writing this article graffiti appeared all over a British advertising campaign for Vauxhall Corsa cars in which supermodels were photographed, supposedly with irony, draped glamorously over cars in the classic ‘woman-as-object’ pose. At the same time a piece of spray-canned graffiti appeared on the wall opposite the London college in which we work which said ‘resist the male gaze’ over a Bunny Club/Playboy motif (see Figure 1). Whether this graffiti was ‘real’ or a spoof slogan was unclear. Certainly, in a college where young female students often say ‘I’m not a feminist but…’ it was heartening to read a feminist slogan imprinted on the masonry. Yet there is a negative implication to this graffiti if it means, as we suspect it does, that ill-formed ideas about ‘the male gaze’ have simply replaced the radical feminist model of ‘patriarchy’.10

Woman as object—feminist critiques

The most familiar article which refers to ideas about ‘the male gaze’ is without question Laura Mulvey’s ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’ (1975).11 But even before she wrote it, many similar ideas about the way women are objectified in Western culture had been raised by feminist critics. Simone de Beauvoir in The Second Sex12 is perhaps the first feminist writer to use the idea of woman as ‘other’.13 De Beauvoir describes at length how she learned to appraise her adolescent self through male eyes during the processes of adornment. As Jane Gaines has pointed out, in de Beauvoir’s writings on this subject ‘there is a premonition of the theory of female representation as directed towards the male surveyor-owner.’14 Later texts from the second wave Women’s Movement, such as Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique (1963),15 Sheila Rowbotham’s Woman’s Consciousness, Mans World (1973)16 and the anthology of feminist writings from the 1970s edited by Robin Morgan, Sisterhood is Powerful,17 all in some way make the association between women’s appearance via fashion, cosmetics and body shape and women’s social inequality and oppression. These books have in common not only an anti-consumer strategy but also the notion that there is some place outside the fashion system for women—a point many subsequent feminist critics have rejected.18 However, the vast majority of feminists do hold on to the idea that women are objectified and this is connected with the experience of being looked at.

John Berger

John Berger’s collaborative book and four TV programmes, Ways of Seeing, which appeared in 1972, were very influential in introducing similar ideas about women’s oppression through objectification to the debate.19 Although Berger does not use the phrase ‘the male gaze’ or psychoanalytic concepts, his analysis has much in common with Laura Mulvey’s subsequent attempt to raise questions about the objectification of women. We start with him because in Ways of Seeing he was strongly influenced by feminism in his discussion of women’s objectification through representation. Berger, like Mulvey, cites representation as a basis for political struggle and cultural intervention and suggests that the perspective of cultural forms like art are not free of social ideologies.

In Ways of Seeing B...