- 1,696 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Management, Quality and Economics in Building

About this book

This book presents the proceedings of an international symposium which aimed to establish at the highest level the best practice and research in three important scientific and technical themes within the domain of residential buildings across the European Community: quality management and liability building economics construction management. In addition the symposium will discuss the future evolution and development of each theme.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Management, Quality and Economics in Building by A. Bezelga,P.S. Brandon in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

MANAGEMENT

1

The client’s brief: a holistic view

P.BARRETT

AbstractThis paper considers the construction briefing process starting with the traditional perspective. Consideration is then extended by viewing briefing, respectively, as communication, leadership and teamwork. The issue of the “worldview” taken of the client is then treated.A holistic view of the briefing process is then presented and, within this context, a contingency approach suggested with the client’s level of knowledge as a major independent variable.Keywords: Briefing, Construction, Holistic View, Project Management, Facilities Management

1 Introduction

Establishing the client’s brief is, of course, a critical step in any construction project. By this means the client’s requirements are set down: time, quality and cost parameters are defined around the central issue of the physical artefact desired by the client. Although this sounds straightforward the process is, of course, complex and the result uncertain. This paper reviews the traditional approach to briefing and then moves on to more complex views.

2 Traditional Views

The Banwell Report stated strongly that clients:

…seldom spend enough time at the outset on making clear in their minds exactly what they want or the programme of events required in order to achieve their objective… (MPEW, 1964)

It recommended that greater effort should be made to establish the brief and further criticised professional advisers for not emphasising that this is ‘time well spent’. It is clear from this that the ideal brief was seen as a well defined input at the start of the construction project.

The way in which the client’s brief links into the construction process is very clearly defined in the RIBA Plan of Work (RIBA, 1967). Here the brief is developed from Stage A (Inception) through to Stage D (Sketch Design) via feasibility studies and outline proposals. It is then stated that the “brief should not be modified after this point”. That is, no change should occur as the scheme is designed in detail, production information prepared, or while the Works are tendered or executed. At the end of the process Stage M allows for ‘Feedback’.

The Plan of Work was criticised in a study by the Tavistock Institute for the “sequential finality” (Tavistock, 1966, p 45) implied by the step-by-step process. The need to adapt to the client’s changing needs and to new information as it comes to light are both stressed (p 47).

A further area of concern raised revolves around the oversimplified use of the term “client” which is often, in reality, an organisation with competing factions. Thus Tavistock use the term “client system” and suggest that there is a need:

…to be very much more aware and responsible in developing the brief through a more conscious understanding of the whole field of social forces they must work with. (p 40)

One reaction to this problem is provided in the Wood Report (NEDO, 1975) which focussed on public sector clients and suggested that:

- a senior officer of the user department should be appointed as the client’s representative for each project to coordinate requirements;

- for large or complex developments, a project manager should be appointed to assume overall responsibility;

Thus, a mechanism to orchestrate the requirements within the client organisation is proposed and the integrating role of the project manager is suggested, typically focussed on the construction team. An erosion of the traditional “linking pin” (Likert, 1967) role of the architect is implicit in the above developments and the need for clear communication between the principal parties is thereby made explicit.

The above reports generally put forward a view that the “traditional” approach to construction in the UK requires a full brief at the start and that this should not be changed thereafter. A dissenting view is provided by the work of the Tavistock Institute. From whichever angle it is viewed successful briefing relies critically on good communication.

3 Briefing as Communication

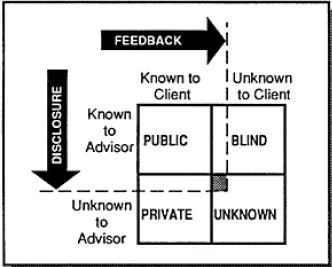

Bejder (1991) insightfully suggests the application of the Johari Window concept (Luft, 1970) to the briefing process. This assists in the analysis of the process of communication involved and highlights possible problem areas. The framework provided by the Johari Window (adapted to the subject analysis) is given in Fig. 1, below:

Fig. 1. Johari Window View of Briefing

From the diagram it is clear that there are four main situations to consider. The “public” area represents the client communicating without difficulty his requirements to the professional advisers. The “blind” area can be seen to be the needs of the client that are identified by the adviser through two-way discussion (feedback) even though the client cannot initially articulate these needs himself. The “private” area relates to the information that the client does not disclose, whether purposefully or not. The “unknown” area is not known to the adviser or the client, but through the twin processes of feedback and disclosure this last area can be revealed, at least in part.

If the brief is to accurately and fully represent the client’s requirements then the importance of advisers encouraging clear disclosure and providing feedback information to the client is apparent. This argues for close and freeflowing discussion possibly over a considerable period. This need not of necessity be limited to the early stages of the project.

The communication process is that much more complicated if the “client” is in fact a group of people or an organisation. In this case the communications must be multistranded both in terms of disclosure and feedback.

In the above briefing is viewed in global terms. Recent work by Gameson (1991) has analysed, at a detailed level, the process of communication between clients and professionals in the initial stages of brief formation. This was achieved by recording the discussions and breaking down the content into categories. The predominant types of interaction were: “giving orientation” (information) and “giving opinions” with, to a lesser extent, “agreeing”. Thus, disclosure and feedback are key areas as anticipated.

A very interesting finding was that the inputs from the parties varied considerably from one case to another depending on the client’s prior experience of construction. For instance, with an experienced client the architect only spoke for 36% of the time, whilst the client made a 64% input. In contrast, taking a case where the client had no previous experience of construction, the comparable percentages were 76% and 24%. A complete reversal.

It is clear from this work that the briefing process will be quite different depending on the experience the client brings with him. This argues strongly for a contingency approach to briefing. The objective is to identify the appropriate approach to briefing in particular circumstances. One independent variable is clearly the project relevant knowledge-base of the client. Are there others?

4 Briefing As Leadership

A fuller view of clients can be obtained by viewing the briefing situation in terms of situational leadership theory. In this literature the distinction is made between the task-related needs of the follower and the sociometric dimension (Hersey and Blanchard, 1982).

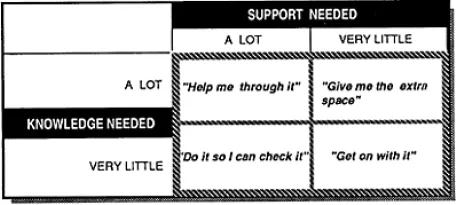

Clients want their professional advisers to do something they cannot, or do not want to, do themselves. The relationship is founded on the adviser giving the client something he lacks. In all commissions the client will expect the professional to “get the job done”, but the actual contribution made may differ considerably, especially at the early briefing stage as shown in Gameson’s work, described above. This work did not however distinguish the two dimensions drawn from leadership theory. Taking these dimensions together a matrix can be formed as shown in Fig. 2, below.

Fig. 2. Typology of Clients Based on Their Needs

The professional is generally leading, providing varying degrees of knowledge and support to the client depending on the client’s particular needs, however, in the case of a very knowledgable, confident client the roles may be reversed with the client taking the lead (influencing). The client types given in the grid can be typified as follows:

Table 1: Suggested Typical Client Types

Although the above model is crude, the message is clear: advisers must diagnose their client’s individual needs if the appropriate input is to be provided to the briefing process.

5 Briefing As Teamwork

The briefing process can be viewed as a team effort between the various parties. There are many categorisations of the various types of team members to be found in a team, however, to be effective such groupings should ideally have complementary abilities, but compatible underlying norms (eg Handy, 1985).

Based on his work in this area Powell (1991) argues that clients should:

- “…understand their own needs first and then… secure a design/build team who will reflect their own view of the world.”

- choose a design team which displays a full range of functional roles and team roles by bringing together a group of complementary individuals thus releasing latent synergy. The functional skills has been discussed above in terms of the knowledge requirements of the project. At an individual level psychosocial factors have also been considered in terms of leadership. Powell’s perspective extends consideration to include the group dynamics necessary for the team to achieve its objectives.

A central point in Powell’s analysis is that:

“the skills required to produce truly user responsive buildings can no longer exist in any one designer/builder”

Thus, the issue of effective groups is inescapable. This is very sweeping and, although undoubtly resonant with a strong trend, it is possible to imagine a private individual with straightforward needs who would be manageable for a single designer.

The principal generator of the overload on the traditional designer is the need to accommodate a wide variety of perspectives within the client system if buildings are to be created that satisfy the wide range of demands. Thus, it can be seen that a fuller appreciation of the client’s requirements leads to the need for a more elaborated construction team. And it is inevitable that the issues of communication and leadership discussed above will be of critical importance within the design team as well as between the client and the “team”.

There is also the question of the contractor’s early involvement which seldom occurs in the traditional approach to construction in the UK. This has long been criticised and various newer approaches are allowing the beneficial inputs possible, such as Design and Build. This radically changes the roles of those involved in construction and other forms such as Design Led and Build are emerging where architects are acting as lead consultants and contractors (Nicholson, 1991). There is not space here to pursue this area, but the issue is clear—the range of factors and involvement is variable on the building team side in just the same way as within the client system.

The above considerations are inextricably linked to the issue of a project management role drawing together the participants within the construction system and focussing them towards the client’s objectives (eg Walker, 1984).

A key factor implicit in all steps of the discussion so far is that the starting point for any analysis should be the choice of view taken of the “client” and the level of complexity thus admitted.

6 Views of the Client

The Lancaster School of Management (eg Wilson, 1984) stresses the importance of the “worldview” (“W” for Weltanschuung) taken of any problem that is being analysed. Solutions found will be inextricably bound up in the orientation of the decision-maker. Ask an architect and you will get a design-biased answer, ask a quantity surveyor and you will get a financially-biased answer, ask an engineer and you will get a technology-biased answer and so on. Over simplified, yes, but broadly true.

Apply this to the question of briefing and it is clear that if an adviser’s “W” of his “client” is of someone who has funds and is looking for a quick return then the briefing process will be quite different in substance and style from an adviser whose “W” includes, say, longer-term issues, the user and society at large.

Obviously the “W” adopted will be conditioned by the client to a great extent, but there are many other forces at work such as education and professional conditioning and simply an awareness of the possibilities.

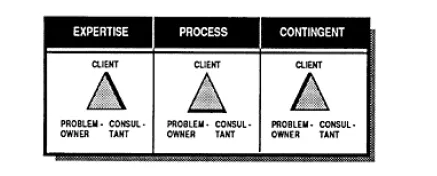

Drawing from his observation of trends in management consultancy (Garrett, 1981) suggests that the consultant will often have to deal with the client and the “problem-owner” (who is often not the client, for example tenants) and that this has led to three different styles of consulting becoming evident. These are shown in Fig. 3, below.

Fig, 3. Garrett’s Alternative Consulting Styles

Expertise consulting is the traditional approach. Process consulting is where the consultant works predominantly with the problem-owner, but this can unsettle the client. Garrett favours contingency consulting which is where the consultant draws out a solution from the client system including both client and problem-owner. This assumes that “…most of the experiences needed to solve a client’s problems are already in the organisation.”

Research by Bejder (1991) in Denmark focussed on University buildings confirms the importance of involving in the briefing process all parties whose needs should ultimately be satisfied. In the study cited the views of students, administrative staff, cleaners, maintenance workers, funders, designers and others were included. Comparing two building phases of the same University it was found that the appropriateness of the involvement in each phase did correlate with the differences found in the quality of the buildings against a range of criteria.

This broadening of perspective when viewing the client system is consonant with recent developments in the field of facilities management (eg Becker, 1990, pp 123–151).

7 Summary

The question of the client’s brief has been approached from a variety of directions. In mapping out the range of factors, and therefore actors, who should be involved it has become clear that the formal, or traditional, view of the process is greatly over-simplified and excludes many factors that can be crucial. This coarsening of the analysis occurs both in the worldview (“W”) taken of the client system and the “W” of the building team. Generally the architect and the particular part of the client system that has the need (the “instigator”) are the focus for the analysis. Fig. 4 shows the parallel trends (Bertalanffy, 1971) within the two systems towards a broader view, symbolised by the project manager in the construction system and the facilities manager within the client system.

Taken together these trends suggest a more holistic view developing which is bound to influence th...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- Part One: Management

- Part Two: Quality

- Part Three: Economics

- Part Four: Information Technology

- Part Five: Policy