eBook - ePub

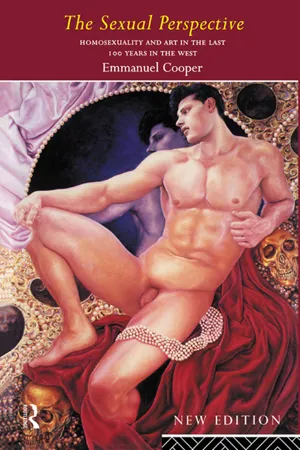

The Sexual Perspective

Homosexuality and Art in the Last 100 Years in the West

- 400 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

First published in 1986 to wide critical acclaim, The Sexual Perspective broke new ground by bringing together and discussing the painting, sculpture and photography of artists who were gay/lesbian/queer/bisexual. The lavishly illustrated new edition discusses the greater lesbian visibility within the visual arts and artist's responses to the AIDS epidemic. Emmanuel Cooper places the art in its artistic, social and legal contexts, making it a vital contribution to current debates about art, gender, identity and sexuality.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Sexual Perspective by Emmanuel Cooper in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & History of Art. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Mirror of the Soul

The great resurgence of interest in Greek art and thought that was a fundamental part of the Italian Renaissance took the perfect male nude as the ideal physical form, able to convey the finest qualities of strength, courage, vitality, nobility, energy and intelligence. While the female nude was descriptive of a particular form of sensuality, the male nude evoked the idea of the perfect society in which man could relate freely and possibly sexually. The perfect male form was considered the mirror of the soul. Conventionally, the male nude in art was thought to be as close to sexual neutrality as the human body could achieve, possessing noble proportions, ideal muscle formations, fine skin quality, well-modelled facial features and strong, alert posture.

If the Greeks aimed to achieve the perfect, sexually neutral body, this was rarely the intention of Renaissance artists who conveyed the all too human qualities of sexual desire by placing the figures in their work in specific situations. The depiction of the male nude was dominated by the expressive brilliance of Michelangelo Buonarroti and by the more scientific approach of Leonardo da Vinci. Other artists responded to their genius and were influenced by their work and ideas. In Northern Europe, the work of Albrecht Dürer had a similar powerful effect.

Within certain privileged sections of Renaissance society homosexuals could be relatively open about their sexual desires while artists could express homosexual subject matter through the use of myth, legend and religion. Dante gives some indication of the prevalence of homosexuality within mediaeval and Renaissance society in Italy when he described it as ‘the vice of Florence’.1 In Italy artists were not required to marry in order to achieve social and professional status as the examples of Leonardo and Michelangelo make clear. This is in marked contrast to Northern Europe where marriage was essential for social respectability. Dürer (1471–1528) married in 1494, very much against his will, and immediately left by himself for Italy.2

Despite the relatively liberal attitudes in Italy, many artists were brought before the courts charged with having committed homosexual acts. It was not possible to live a completely free and open homosexual life. But the structure of society and the general liberal attitude did permit homosexual activities and relationships to a degree. The system of young apprentices working in the artists’ studios provided opportunities for sexual friendships to develop without attracting public attention.

In Northern Europe there was generally less tolerance of homosexual behaviour and even successful and famed artists were persecuted with the full force of the strict law. In 1654 the internationally known Belgian sculptor and engraver Jérôme Dusquesnoy (1602–1654) was accused of having abused two boys in the Chapel of Ghent. After several periods of interrogation he was sentenced to death. Despite pleas from royal and religious patrons, he was lashed to the stake, strangled and burned in the City Grain Market.

Many artists found great inspiration in neoplatonist philosophies and particularly in the ideas of Marsiglio Ficino who had translated Plato’s writings. Neoplatonism sought to reconcile and combine the philosophy of the ancient Greeks and the beliefs of the Christian church. In neoplatonist circles there was also great emphasis placed on the importance of the subjective expression of the individual artist. This was very different from the mediaeval tradition in which the emphasis had been on the expression of objective Christian truth when the artist was more often than not an anonymous artisan. It was a philosophy which regarded beauty, particularly that of the male body, as the visible evidence of the Divine, and it followed that it was possible to express solemn and even religious sentiments through classical themes.

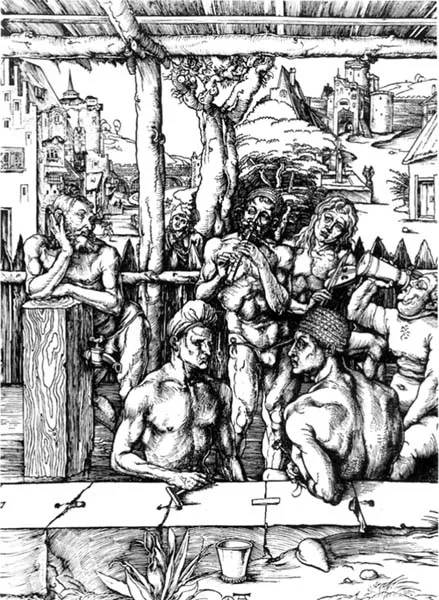

For many, admiration for the classical Greeks and their way of life implied an acceptance of homosexual relationships. In the eighteenth century, when interest in the ancient civilisations intensified, Winckelmann’s admiring studies of Greek culture recognised that homosexual relationships were common and accepted within it. Other artists and writers looked back at the society of ancient Greece as a ‘Golden Age’, free from guilt, when the male body in all its unadorned splendour could be freely admired as an object of sexual desire and beauty. Such open expression is unusual in Western culture. At other times various codes and other means have been developed through which homosexual themes can be expressed. One of the more obvious situations in which homosexual sentiments could be expressed acceptably was in the male bath house. Michelangelo included such a scene in the background of the Doni Tondo and Caravaggio set The Martyrdom of St Matthew in a bath house. In Northern Europe, Dürer’s engraving Men’s Bath introduced specific erotic allusions with penis-shaped taps and tree trunks and so on making the sexual content explicit.

In Italy, Donatello (1384–1460) and Botticelli (1445–1510) were two of the first artists to explore the possibilities opened up by the new found freedoms of the Renaissance. Stories and gossip about Donatello’s homosexual relationships with his assistants abounded. Born Donato di Niccolo Donatello, he became one of the most influential artists of the fifteenth century, giving his prophets and saints a sinewy vitality and a particularised character which implied first-hand study from life.

The most specifically sexual example of his sculpture, David c. 1430–32 (Bargello, Florence), is one of his most homoerotic. The bronze David is a youthful figure standing some five feet high, one foot resting on Goliath’s helmet. The feather from the wing on the helmet curves gracefully up the side of his leg and gently tickles his crotch, a studied rather than an accidental placing. The David originally stood in the garden of the Medici Palace and would have been seen and admired by Michelangelo.

Botticelli (1445–1510) was born Alessandro di Mariano Filipepi in Florence. He studied in Filippo Lippi’s workshop, getting his first commission around 1470. Intellectually he was stimulated by the new philosophies, although often torn between solemn religious beliefs and pagan ideas. Commissioned by Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de’ Medici, a wealthy Florentine with interests in Platonic philosophy, he painted some of his most famous mythological paintings including The Birth of Venus c. 1481 (Uffizi Gallery, Florence). Much of his work has a delicate if melancholic sentimental grace, with an emphasis on the flowing quality of linear movement. In his portrayal of women, whom he often painted nude, he conveys a modest sensuality while giving them a feeling of unreality. It was these women who were the great inspiration for the English Pre-Raphaelite painters in the nineteenth century.

In contrast, the males in Botticelli’s paintings, in particular the angels in the religious pictures, explore a wider range of ‘types’. Traditionally angels were minor characters, taking secondary roles. They were asexual since theologically they were neither male nor female. For the homosexual, this offered a particular means of identification which could be used to suggest a ‘third sex’. Hence Botticelli’s angels are given an ambiguous sexuality. In the Mystic Nativity c. 1500 (National Gallery, London) angels surround the byre with the infant Jesus. They embrace and gesticulate, generally animating the central scene. In this later painting, the angels are more flamboyant and feminine than in the Madonna of the Magnificat c. 1480 (Uffizi Gallery, Florence). The group of four wingless angels is almost totally self-absorbed. Rather than attending to the infant and the Madonna, with their flowing locks and smooth cheeks they direct their tender, adoring concern at each other. The look of innocence and of sensual pleasure of these angels contrasts with the more worldly, knowing glances of the group in the Madonna of the Pomegranate c. 1490 (Uffizi Gallery, Florence). Though they carry such items as a garland of red roses and lilies, symbolising Mary’s purity and love, they show no interest in the mother and child and are more concerned with gossiping or gazing directly out of the picture.

1.1 Albrecht Dürer (1471–1525) The Bathhouse (detail). Wood engraving. Homoerotic allusions abound, for instance in the shape and position of the water spout, in the form of the tree trunk, the plants, rocks and so on

1.2 Donatello (1386–1466) David (c. 1430). Bronze. Height 158 cm (62 in) (Museo Nazionale, Florence)

An altarpiece of much the same date Virgin and Child with Saints (Sta Barnaba, Florence) demonstrates Botticelli’s skills in handling a large composition as well as his sensitive delineation of individual character. Despite their sweet looks, the angels are worldly and knowing. The three saints who stand on the right, St John the Baptist, St Ignatius and the Archangel Michael, are almost life size and each has a distinct and dramatic presence. St John is taut and anguished, St Ignatius, known as ‘the beloved of Christ’, is old and sagacious, while the youthful, smoothfaced Archangel Michael wears his armour lightly, with a peaceful, almost languid pose which suggests that it is highly improbable that he should be involved in war.

1.3 Sandro Botticelli (1445–1510) Madonna of the Magnificat. Diameter 112 cm (44 in) (Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence)

In 1502 Botticelli was anonymously accused in the Uffiziali di Notte, the institution through which Florentine citizens were able to denounce each other for real or imagined crimes, of committing sodomy with one of his assistants. Such information gives weight to the analysis that Botticelli’s work was not merely about the formal relationship between Christianity and classicism, but also contains an expression of his own concerns. Interestingly, Botticelli never left the family home but lived and worked there until his death. Vasari3 relates that Botticelli came under the influence of Savonarola who particularly condemned ‘the love of beardless youths’ in 1494. He produced little work in his later years, although he did continue working for Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de’ Medici. His work may have been inhibited by an awareness that he had been eclipsed by other artists and his trial in 1502 may have had a profound psychological impact.

The struggle to find an acceptable voice with which to describe a forbidden sexuality is central to the work of Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo. They were very different in temperament and approach and both professionally and sexually they were rivals. So talented and able were they that in any other society the two men might have taken up other professions. In Renaissance Italy, art was the profession outside of the church which offered the freedom and scope for their brilliant abilities, energies and sexual interests.

While Leonardo (1452–1519), the elder of the two, was generally outgoing, gentle and without deep religious beliefs, Michelangelo (1475–1564) was more introverted, often withdrawing from society and friendships sometimes for years on end, and he was deeply religious. Both artists have become victims of a profusion of myths and labels around their lives and their work. Some writers ignore the question of sexuality, while others deny that the basis of both artists’ work is a great love and sexual desire for members of their own sex.

Leonardo da Vinci, the model of the ‘true renaissance man’, was learned in a wide range of sciences, art and invention. Vasari,4 the greatest source of information on Leonardo, describes him as having ‘a personal beauty (which) could not be exaggerated, whose every movement was grace itself’. Other writers also noted his handsome good looks and his ‘beautiful head of hair which he wore curled down to the middle of his neck’.5 Vasari describes Leonardo as ‘nearer to being a philosopher than a christian’. As a humanitarian he bought and released caged birds and he ate no meat because of his love of animals, yet he spent days dissecting decaying corpses or designing war machines.

At the age of twenty-four, Leonardo was implicated in an anonymous denunciation of homosexuality.6 The accusation involved a seventeen-year-old male prostitute, Jacopo Saltarelli, who was said to have had homosexual relations with several men including Leonardo and Leonardo’s teacher, Verrocchio. All were acquitted. Leonardo’s sexual interests centred on younger men, many of whom he took on as assistants. One of these was Salai (a nickname meaning ‘little devil’), ‘an attractive youth of unusual grace and good looks, with very beautiful hair which he wore in ringlets and which delighted his master’. Vasari’s description fits one of Leonardo’s favourite ‘types’ of men, the androgynous youth. Salai seems to have been hopelessly spoiled and indulged by Leonardo. In 1497 a bill for expensive clothes for Salai prompted Leonardo to write ‘This is really the last time, dear Salai, that I am giving you more money.’7 Nevertheless, he lived with Salai for eighteen more years. Other close friendships were formed with his assistants who were as likely to be selected for their beauty as for their talent. It is worth noting that none of his assistants gained a reputation as an artist. Francesco Metzi lived with Leonardo until his death and inherited much of his estate which included clothes, books, notebooks, drawings and portraits. Part of his garden was left to his servant Batista de Villani and the rest went to Salai.

In 1472 at the age of twenty, Leonardo was taken on as an apprentice in Verrocchio’s studio and he may have posed for Verrocchio’s statue of David (Bargello, Florence) which was made around this time. Leonardo established one of his most significant types, the androgyne, in his first surviving figure painting, an angel in Verrocchio’s Baptism of Christ by St John (Uffizi Gallery, Florence). The angel’s face is rounded, the cheeks fruit-like, the hair abundant and delicate. The type persists throughout Leonardo’s work. Similar characteristics occur in his last picture, the St John in the Louvre. The androgynous figure of the saint conveys a beatific mystery in the sensual, rounded flesh and ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Introduction to Second Edition

- 1 The Mirror of the Soul

- 2 Free from the Itch of Desire

- 3 Genius has no Sex

- 4 Sexual Aesthetes

- 5 The Soul Identified with the Flesh

- 6 The Sexual Code

- 7 Breaking Out: Private Faces in Public Places

- 8 The New Woman

- 9 The Divided Subject

- 10 Veiling the Image

- 11 Lesbians Who Make Art

- 12 There I Am

- 13 Shouting and Singing

- Notes

- Biographies and General Reference

- Index