- 400 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

A comprehensive and balanced volume which juxtaposes the views of statesmen with those of military leaders that fought the war.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Suez-Sinai Crisis by Moshe Shemesh,Selwyn Illan Troen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Middle Eastern History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

INTRODUCTION

1

The Suez-Sinai Campaign: Background

Chaim Herzog

THE POLITICAL BACKGROUND

During the seven years following the signing of the Armistice Agreements, instead of peace treaties being achieved as envisaged in the preambles to the agreements, the rift between Israel and the Arab states widened, and the relations along Israel’s borders (apart from that with Lebanon) deteriorated. The Arabs persisted in their policy of refusing to accept the fact that Israel existed as a sovereign state, a member of the international community and an independent entity. Whilst the War of Independence, as a war, had been fought and was, physically speaking, over, its causes and the motives behind the enmity of the Arab states against Israel continued to exist and to brew. Within months of the signing of the 1949 Armistice Agreements, border incursions, raids, economic warfare and other violations became the order of the day. By 1954, it was clear that the incursions of fidaiyyun murder groups were not isolated incidents, but, like the economic sanctions against Israeli commercial and maritime interests, were organized and implemented with the knowledge and co-operation of the Arab governments.

The major Arab defeat in 1948 exacerbated many of their internal problems, bringing to the fore the extreme elements and creating an atmosphere of unrest and near-revolution in many of the Arab countries. In July 1951, King Abdulla of Jordan, who had secretly initialled an agreement intended to lead to a peace accord with Israel, was assassinated, struck down by the agents of the Mufti of Jerusalem, Hajj Amin al-Husseini, on the steps of the al-Aqsa Mosque on the Temple Mount in Jerusalem. (His grandson Hussein, who was to be proclaimed King of Jordan a year later, was at his side.) In Egypt, the Egyptian Prime Minister, Nuqrashi Pasha, was assassinated in the aftermath of the war. The Syrian Government was overthrown by General Husni al-Za’im in 1949, and he in turn was overthrown in 1951; thereafter, Syria was to be torn by frequent military revolutions until the advent in 1970 of President Asad. In Egypt, a group of so-called ‘Free Officers’ led by Lieutenant-Colonel Gamal Abd al-Nasser seized control of the government on 23 July 1952 and sent King Farouq into exile. For a period, the officers appointed as their leader General Muhammad Naguib, who had emerged from the 1948 war as a popular figure, but he was soon deposed and full authority over the new republic was assumed by Nasser. (One of the leading members of the Free Officers group who participated in the revolution was Lieutenant-Colonel Anwar al-Sadat, later to be the President of Egypt and the first Arab leader to sign a peace treaty with Israel.) In Jordan, moves made by the British government to induce the Kingdom to join the Western Middle East alliance known as the Baghdad Pact provoked riots in December 1955. This extreme reaction was brought about by an anti-Western, pro-Nasser change of direction in the Jordanian government: Glubb Pasha and the British officers serving in the Arab Legion were dismissed summarily, and thereafter armed incursions from Jordan by fidaiyyun groups frequently attacked objectives in Israel.

The rise of Nasser to power in Egypt was welcomed at first by Israel. Indeed the aims of the revolution and initial contacts with Nasser’s regime inspired hope for the future. But Nasser’s mixture of radicalism and extreme Arab nationalism, coupled with an ambition to achieve leadership in the Arab world, pre-eminence in the world of Islam and primacy in the so-called non-aligned group of nations (which, with Presidents Tito and Nehru, he founded), gradually came to expression in a bitter, blind antagonism to Israel. It was to lead Egypt to tragedy.

In late 1955, a massive arms transaction between Egypt and Czechoslovakia was concluded, whereby Egypt received modem weapons. This, as Nasser declared, constituted a major step toward the decisive battle for the destruction of Israel. Egypt received 530 armoured vehicles (230 tanks, 200 armoured troop carriers and 100 self-propelled guns), some 500 artillery pieces, and up to 200 fighter, bomber and transport aircraft, plus destroyers, motor torpedo-boats and submarines. Thus was established the first major Soviet foothold in the Middle East. This arms agreement with the Eastern bloc was a major boost to Nasser’s ambitions. He was now establishing himself as the leading element hostile to ‘Western imperialism’ in the Middle East, and becoming a serious embarrass-ment to the British and French in the area. Besides supporting radical governments in Africa and backing the fidaiyyun raids on Israel, he was active in helping the FLN revolutionaries in Algeria against French rule. This, however, created a bond of common interest between Israel and France, as a result of which Shimon Peres (then the dynamic Director-General of Israel’s Ministry of Defence) was able to promote various areas of co-operation between the two countries. Israel now began to receive shipments of arms from France (although sufficient only to prevent Egypt’s superiority in weaponry from exceeding four to one on the eve of the Sinai Campaign).

Egypt meanwhile blocked the passage of Israeli vessels in the international waterways of the area in violation both of the 1949 Armistice Agreement and of international law. In order to reach the Red Sea and maintain commercial and maritime contacts with the Far East and Africa, Israeli vessels had to navigate through the Straits of Tiran, which Egypt had blocked by installing a coastal artillery battery at Ras Nasrani. Egypt had also barred all passage by Israeli vessels through the Suez Canal—despite a resolution of the United Nations Security Council in 1951 censuring Egypt’s policy on this issue. But, even after this resolution, Egypt, aided politically by the Soviet Union, extended the maritime limitations, impounding Israeli vessels, cargo and crews.

In the course of negotiations with Great Britain, Nasser negotiated the withdrawal of British troops from the Suez Canal zone, where they had been stationed for over 80 years by treaty. He was also negotiating with the United States government and with the British government for a loan from the International Bank for reconstruction and development to finance the construction of a dam on the river Nile above Aswan. This would supply electricity, control the Nile floods and by irrigation increase considerably the area of arable land in Egypt. At the same time, he conducted parallel negotiations on this project with the Soviet Union. But his attempt to play off West against East on this issue aroused the wrath of the United States Secretary of State, John Foster Dulles, who in July 1956 withdrew the American offer to finance the dam. Infuriated, Nasser nationalized the Suez on 26 July 1956 by seizing control from the Suez Canal Company, in which the British government held a majority share, and abrogating the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty. Seeing the seizure of the canal as a threat to their strategic interests—including their oil-supply routes—the British and French began to prepare contingency plans. Forces were moved to Malta and Cyprus in the Mediterranean in preparation for the seizure of the Canal Zone and, indirectly, to bring about Nasser’s downfall. Such a campaign, whilst objectively independent of the local Arab-Israeli problems, naturally had its implications—a factor that undoubtedly contributed to the decision-making process prior to the start of the campaign.

By this time, the Israeli leadership had reached the conclusion that Nasser was heading for an all-out war against Israel. This could be the only explanation for the joint military command established in October 1955 between Egypt and Syria (to be expanded in 1956 to include Jordan). The blockade of the Suez Canal and the Gulf of Aqaba was part of an all-out economic war against Israel, while the fidaiyyun incursions into Israel were becoming more frequent and exacting greater numbers of casualties—some 260 Israeli citizens being killed or wounded by the fidaiyyun in 1955. The Egyptians would very rapidly absorb the weapons supplied by the Soviet bloc. It was clear that Israel could not allow Nasser to develop his plans with impunity. Accordingly, in July 1956, David Ben-Gurion decided that he had no option but to take a pre-emptive move, and gave instructions to the Israeli General Staff to plan for war in the course of 1956, concentrating initially on the opening of the Straits of Tiran.

Israel meanwhile mounted diplomatic efforts to expedite the supply of arms from France. According to Moshe Dayan, the Chief of Staff at the time, the Israeli Military Attaché in Paris cabled on 1 September 1956, advising him of the Anglo-French plans against the Suez Canal and informing him that Admiral Pierre Barjot, who was to be Deputy Commander of the Combined Allied Forces, was of the opinion that Israel should be invited to take part in the operation. Ben-Gurion’s instructions were to reply that in principle Israel was ready to co-operate. An exploratory meeting took place six days later between the Israeli Chief of Operations and French military representatives, while Shimon Peres continued talks in Paris with the French Minister of Defence, Maurice Bourgès-Maunoury. At the end of the month, an Israeli mission headed by Foreign Minister Golda Meir, and including Peres and Dayan, met a French mission that included the French Defence Minister and the French Foreign Minister, Christian Pineau. As the preparations were set afoot to strike at Egypt, Franco-Israeli meetings became more frequent. Then, on 21 October, at the invitation of the French, Ben-Gurion flew to Sèvres in France, accompanied by Shimon Peres and Moshe Dayan. At these negotiations, in which the French Prime Minister, Guy Mollet, participated, they were joined by a British mission consisting of the British Foreign Minister Selwyn Lloyd and one senior official. After much discussion, during which Ben-Gurion was very hesitant because of his innate lack of trust in the British, the plan was arranged in such a way that Israel’s first moves would not be interpreted as an invasion, and its forces could be withdrawn should the British and French allies not fulfil their part of the agreement.

A further factor affecting considerations was the way in which both the United States and the Soviet Union were preoccupied in such a manner (or so it was estimated) as to limit their freedom of action at the time. The United States was in the throes of a Presidential election, during which it was assumed that President Eisenhower would not take any vital international decision that might prejudice his chances of re-election. Similarly, the Soviet Union was busy during the three months prior to the campaign, quelling the national urge for liberalization that had begun to come to expression in Poland and Hungary.

By October 1956, the Egyptian threat to Israel had taken on an increasingly active form. Fidaiyyun raids reached an all-time high, in both intensity and violence, and the Israeli reprisal policy did not supply any final, secure or convincing answer. This and the prevailing global situation placed Israel in a position in which it had to take advantage of the circumstances in order to break the Egyptian stranglehold on its commercial sea routes and along its border areas. The aims were to be threefold: to remove the threat, wholly or partially, of the Egyptian Army in the Sinai; to destroy the framework of the fidaiyyun; and to secure the freedom of navigation through the Straits of Tiran. Only thus would Israel place itself in a comfortable bargaining position for the political struggle that would undoubtedly ensue.

The Israeli command had succeeded in creating an artificial tension with Jordan thus giving the impression that Israel’s mobilization—as and when it would be noticed, as doubtless it would be—was in preparation for action against the Jordanians. Following the murder of two Israeli farm workers an attack was launched on 10 October on the frontier town of Qalqilia, and King Hussein invoked the Anglo-Jordanian Defence Treaty against Israel. This operation, costly to Israel, did however concentrate the area of tension along the Jordanian border and not Sinai.

THE MILITARY BACKGROUND

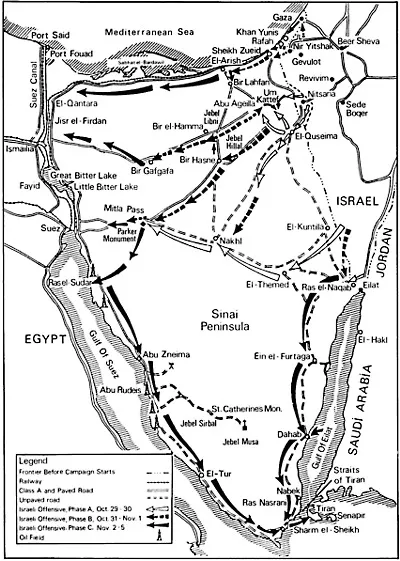

The Sinai Peninsula is a parched desert area in the form of an inverted triangle, serving as both a connecting corridor and a dividing barrier between Egypt and Israel. It provides either side with an ideal jumping-off ground in an attack against the other. The northern side, on the Mediterranean coast, is 134 miles long; its western side, along the banks of the Suez Canal and the Gulf of Suez, is 311 miles long; and its eastern side, along the Gulf of Aqaba, is 155 miles long. Topography in the northern half ranges from undulating sand dunes and ridges, palm groves and salt flats along the coastal plain, to a central hilly area with a vertical range of ridges reaching heights of up to 3,500 feet. Here there are but limited axes for passage, through which Egypt had constructed main roads, utilizing the negotiable passes between the high ridges and the deep, powdery-sandy wadis. The lower half of the peninsula represents the most extreme forms of desert topography—steep, saw-tooth mountain ranges, deep powdery wadis devoid of water, greenery and negotiable roads. The only passable road built in this area by the Egyptians had been, in fact, the coastal road connecting Suez, Ras el-Sudar, el-Tur and Sharm el-Sheikh along the coast of the Gulf of Suez.

The nature of the territory dictated over the centuries the course of the warfare in the Sinai, a form of warfare concentrated on the negotiable routes and on the critically strategic ridges overlooking such routes. In the Sinai, there are no rivers, forests or jungles: the conflict is predetermined by the demands of the desert, and this in fact is clear from the battles waged there in 1956.

On 29 October 1956, at 1700 hours, an Israeli parachute battalion under command of Lieutenant-Colonel Rafael (‘Raful’) Eitan, who was many years later to be Chief of Staff of the Israel Defence Forces, and part of the 202 Parachute Brigade commanded by Colonel Ariel Sharon, dropped in central Sinai at the eastern entrance to the Mitla Pass 156 miles from Israel and 45 miles from the Suez Canal. Two hours before the parachuting of the forces at the Mitla Pass, four Israeli piston-engined P-51 Mustang fighters carried out a hair-raising operation. Descending to 12 feet above the ground, they cut with their propellers and wings all the overhead telephone lines in the Sinai connecting the various Egyptian head-quarters and units. The nature of this attack kept the Egyptians guessing for some 24 hours as to the real purpose of the operation. At the same time the remainder of the brigade, commanded by Colonel Ariel (‘Arik’) Sharon moved out of its concentration area near the Jordanian border, crossed the Negev Desert and developed its drive across the Sinai, passing Kuntilla, Themed and Nakhl. Heavy fighting soon developed at the Mitla Pass.

The second major battle was that to neutralize the main concentration of Egyptian forces in the Sinai, the defended localities of Quseima/Abu Ageilla and Um Kattef, and to overrun the central axis from Quseima to Ismailia. This front blocked the main central axis that, if opened, would ensure the success of the campaign, as it would open up an alternative transport and supply route from Israel to Sharon’s brigade at the Mitla Pass. The task was entrusted to the 38th Divisional Group commanded by Colonel Yehuda Wallach, and comprising the 4th and 10th Infantry Brigades and the 7th Armoured Brigade commanded by Colonel Uri Ben Ari. At a certain point G-o-C Southern Command Major-General Assaf Simhoni advanced the entry of the crack 7th Armoured Brigade into the battle.

By the morning of 2 November the Israelis had completed the assault on the Abu Ageilla/Um Kattef system of defence, thus opening up a good-quality supply route to the forces at the Mitla Pass and along the central axis, and cut off the Egyptian garrison in the Gaza Strip. A divisional task force under Brigadier-General Haim Laskov, comprising the 1st Golani Infantry Brigade under Colonel Benjamin Gibli, and the 27th Armoured Brigade under Colonel Haim Bar-Lev, broke through the Rafah camp area and the area of the Rafah junction in order to open up the route to el-Arish and northern Gaza. One of the battalions was commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Meir Pa’il.

The Sinai Campaign 29.10–5.11.1956

A major battle took place here, and on 2 November the 27th Armoured Brigade entered el-Arish and continued westward. Meanwhile the Israeli 11th Brigade under Colonel Aharon Doron was dealing with the 10,000 Egyptian troops, particularly the Palestinian 8th Division, in the Gaza Strip. By 3 November the area had been mopped up.

Perhaps one of the more dramatic moves was that of the 9th Infantry Brigade, commanded by Colonel Avraham Yoffe, which advanced along the rough west coast of the Gulf of Aqaba and negotiated a desert and mountain route nothing more than a camel route, over which no motorized unit had ever moved. The brigade negotiated the distance to Sharm el-Sheikh with 200 vehicles and 1800 men against sporadic resistance, but almost impossible physical ground conditions.

In the meantime the paratroopers had moved down from the north to Sharm el-Sheik, and on the morning of 5 November the 9th Brigade took control of the locality which was blocking the Straits of Tiran, and met up with units of Sharon’s parachute brigade which had moved down along the Gulf of Suez.

In the initial air battles Israeli superiority was achieved in some 164 air encounters. Later, as French and British aircraft began to bomb Egypt, Egyptian air activity was reduced to a minimum. Thus by the morning of 5 November the Israeli forces had reached the Suez Canal and had opened the Straits of Tiran at Sharm el-Sheikh.

Meanwhile, the allied forces had planned an operation that obviously envisaged heavy opposition on the part of the Egyptians, and indicated their adherence to the set-piece type of battle they apparently anticipated. Consequently, the allied task force set sail only on 1 November from Valetta Harbour in Malta. There is no doubt that the results would have been completely different had the British Prime Minister, Anthony Eden, taken the advice of General Sir Charles Keightley and Lieutenant-General Sir Hugh Stockwell (who had command of British forces in Haifa in 1948 and was now commander of the Allied Land Forces) to effect the landing on 1 November as was originally planned. This would have changed the entire pattern of developments and would have avoided many of the subsequent political issues.

The British forces at sea included an infantry division, a parachute brigade group and a Royal Marine commando brigade, while the French forces included a parachute division, a parachute battalion and a light mechanized regiment. There were also the naval forces of both countries and air forces operating from the British and French aircraft carriers and from Cyprus. As this force was making its way slowly across the Mediterranean, to be joined en route by French units from Algeria and British units from Cyprus, political pressure from the Russians and in the United Nations increased, and the political limitations imposed on the British and French forces grew. They were hampered by a growing degree of hesitation on the part of the political leadership, particularly in Britai...

Table of contents

- COVER PAGE

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT PAGE

- MAPS AND ILLUSTRATIONS

- PREFACE

- PART I: INTRODUCTION

- PART II: THE BELLIGERENTS

- PART III: THE SUPERPOWERS

- PART IV: PARTICIPANTS RECORD THE EVENTS

- APPENDIX