1

COMMUNICATION STUDIES SOME BACKGROUND

A first communication model

Some communication terms

Audience, medium and message

Examinations and skills

Summarizing texts

How to write press releases

Audience: the traditional literary view

Communication studies and the tigers

A first communication model

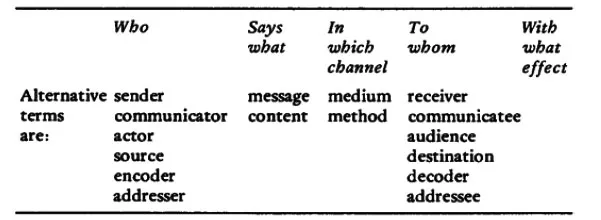

A simplified linear method of representing what happens in the mass communication process was proposed by Harold Lasswell (1948). His model suggests that we ask the following basic questions of each act of mass communication (e.g. on television and radio or in the press):

It will be useful to ask these questions of forms of communication other than mass.

Berlo (1960) defines ‘encoder’ and ‘decoder’ thus: ‘The communication encoder is responsible for taking the ideas of the source and putting them into a code, expressing the source’s purpose in the form of a message…. Just as a source needs an encoder…the receiver needs a decoder to retranslate, to decode the message and put it into a form that the receiver can use.’

Some communication terms

The use of alternative terms by writers on communication indicates how new the subject is in comparison with others. As study deepens, greater precision in the use of terms is called for: ‘channel’ and ‘medium’, for example, have been further distinguished in this way. A channel is a physical means of transmitting a signal, including therefore radio, light and sound waves, telephone cables and the body’s nervous system. A medium consists of the technology or physical method by which the content or message is changed into a signal that can be sent along the channel. Thus television and radio sets are media; they cannot transmit messages (programmes) to us without the use of the channels of light, sound and radio waves; the telephone is the medium, the telephone cable the channel. One medium may carry to the receiver messages originally sent in another medium. The telephone carries a voice—a medium which is dependent on the physical channels of the nervous system and sound waves. The television set carries a second medium when it shows a feature film made originally for the cinema.

A code includes (a) physical signs that represent things other than themselves (e.g. verbal signs: words and signs based upon verbal signs such as semaphore, braille and morse code); and (b) the rules for using these representational signs, and the conventions which decide how, when and where these signs may be meaningfully used to convey messages. People who share a common culture, or sub-groups within the culture, use codes. The physical properties of a channel will thus determine the type of code that can be used in that channel. Since the physical channel of the telephone medium excludes visual signs, the telephone is restricted to the use of words and their emphasis through volume, stress, intonation, etc.

There are two types of ‘noise’ that can interfere with communication and thus severely affect the meaning that is intended: ‘channel’ and ‘semantic’. Channel noise includes any type of noise that affects the accuracy of the physical transmission of the message. Examples from the mass media include smudged ink in the newspaper due to a fault in the printing process, or interference on a television picture from unsuppressed motor vehicles. Examples from interpersonal communication include somebody speaking over another during a conversation; and from medio communication, a crossed line on a telephone. (For an elaboration of the main types of communication, see chapter 2.) Semantic noise occurs where there is distortion because of the way in which codes are used by the encoder and the decoder, rather than because of the physical nature of interference. The interpretation of the message is therefore not what the sender (encoder) intended.

The message sent to the receiver can also be affected by feedback, as the receiver ‘feeds’ his/her reaction to the message back to the sender. If the person sending the message is a sensitive communicator, s/he will take account of the information s/he gets from the receiver in order to modify aspects of the message as necessary.

Having introduced some basic communication terms and a model, this first chapter includes relatively little by way of communication theory. Most of it is taken up with documents that are the basis for assignments for you to attempt. Your immediate involvement with communication tasks will provide the best basis on which to reflect on the communication process taking place, and thus build your later understanding of communication principles, concepts and models.

This chapter also attempts to give you a general picture of some of the background to the relatively new field of communication studies by presenting material that focuses on why and how things are changing in language, literature and communication studies in our schools and colleges. The material included concerns developments that have given rise to the sort of communication studies course you are likely to be following. It is drawn from a variety of sources that use a variety of channels, codes and media to produce messages aimed at a variety of audiences. While undertaking case-study and project work you will be involved in a much greater range of channels, codes and media than are employed in this book, whose message is inevitably determined to a certain extent by the limitations of its medium: print.

DOCUMENT 1

Extracts from a survey that investigated reasons why students are taking communication studies courses

We shall begin by taking a sample of more than a hundred students in the first year of their course (AEB ‘A’-level in communication studies) and asking what they hoped for and wanted from it. Their perceptions at this stage offer another guide to the aims in the process of realization.

‘I wanted to do something new.’ ‘lt is a challenge.’ Not every student will be prepared at 16-plus to opt for what may look like a totally new subject. For those who do, that sense of breaking new ground (and knowing that your teachers are doing so too) may itself be a stimulus. In communication studies the territory is not altogether unfamiliar, but the idea of studying it systematically is an extension beyond any previous course. ‘I thought it would open up as wide and varied a field as possible.’ ‘Many ‘A’-level subjects are specializing in one particular area…. I chose this course because of its broadness.’ ‘lt seemed a very wide subject, which I could later on choose one aspect of perhaps, because I’m not sure exactly what I want to do.’

We have already noted the major recommendation that courses at ‘A’-level, while allowing for early specialization in some cases, should also be providing for a delay in specialist choice. If communication studies combines a broad offering with the possibility of developing specialist interests later in the course, this is a major contribution to fulfilling such recommendations. The question is, how will teachers develop a course that meets the desire to ‘broaden my knowledge’ while at the same time ensuring that ‘a student can concentrate on those areas that interest him most’? In some ways this seems to call for new forms of group work or individual assignments.

There were other indications that students would differ both in what they might well contribute to the course and what they might be relating communication studies to in the rest of their work in college or school. ‘lt was an obvious choice with English literature and film studies’, wrote one student. Indeed in our sample, English literature is the ‘A’-level most likely to be taken in association with communication studies. But there are other and different possible associations. ‘Chosen to help further my knowledge of the background to art work, i.e. how we are affected by visuals.’ ‘Seemed to offer a practical supplementary study to my other subjects— sociology and political studies.’ ‘A useful subject to combine with my languages, French and German.’ In addition, though they were not represented in our sample, we have been working with one college where the majority of students were taking science ‘A’-levels. (Dixon, 1979, p. 71)

ASSIGNMENT A

(Document 1)

Communicator

1.Explain briefly, giving reasons, who you think the ‘we’ in the document is.

Audience

2. Explain briefly, giving reasons, at whom you think the document is aimed.

Context

3.Explain briefly, giving reasons, where you think the document was first published.

Content

4.Summarize in not more than 150 words the message contained in the document.

Layout

5.Given the audience at whom you believe the document is aimed, suggest possible ways of setting it out more clearly by changing punctuation, paragraphing and sentence order.

DOCUMENT 2

Main reasons for choosing the communication studies course

The following comments by students, made half way through their first year, offer some insights into their motivation and interests:

WHY?

‘A challenge, as I wanted something different from the ordinary courses available.’ ‘Different to all the previous subjects I had taken.’

‘Relevant to everyday life.’ ‘lt seemed a relevant subject in that it deals with the role of the media in our lives.’

‘Useful subject in any job.’

‘Fits in with other ‘A’-levels, e.g. social sciences, all of which inter-relate.’

‘Run in conjunction with psychology and sociology and is described as a “social behavioural course”.’

Greater understanding of the way in which society works.’

‘lt should mean that I can express my ideas clearly.’ ‘Helps me improve my own communications.’

‘Many ‘A’-level subjects are specializing in one particular area; the communication course covers such a wide area that a student can concentrate on the sections which interest him most.’ (From the Schools Council Survey, 1978)

DOCUMENT 3

What is communication studies—and why you s...