1

Empiricism and theoretical discourse

Scientific theories posit a number of unobservable entities and employ theoretical terms—e.g. ‘electron’, ‘proton’, ‘electromagnetic field’, ‘DNA molecules’, etc. (henceforth, t-terms). How is this theoretical discourse, the discourse involving t-terms, to be understood? There are two broad philosophical traditions—an empiricist and a realist tradition—each with an answer to this question. Broadly speaking, the empiricist tradition aims to show that theoretical discourse may be so construed that it does not commit to the existence of unobservable entities. The realist tradition, on the other hand, aims to show that a full and just explication of theoretical discourse in science requires commitment to the existence of unobservable entities. The dialectic of the debate between the two traditions which will be explored throughout Part I will show how forceful the realist position is.

The empiricist tradition is actually multi-faceted. Concept empiricists have always tied meaningful discourse to the possibility of some sort or another of experiential verification. According to the verification criterion of meaning, assertions are meaningful if and only if they can be verified. Some empiricists suggest that observational terms, such as ‘is red’, ‘is square’, ‘is heavier than’, get their meaning directly from experience: the conditions under which assertions involving them are verified coincide with the conditions under which they are true. But when it comes to t-terms things are different. Assertions involving them cannot be verified. This seems to create a problem. Are theoretical terms meaningless? Are theoretical assertions (henceforth, t-assertions), then, not genuine assertions?

Reductive empiricists argue that they need not be. But, they note, insofar as tassertions have meaning, it is because they are really assertions about observable entities (henceforth, o-entities): they are just disguised talk about o-entities.1 How can that be? Reductive empiricists think that semantics might be able to cover for metaphysics. An assertion which prima facie commits one to some undesirable entity, e.g. a t-entity, need not be so committing. For the truth-conditions of such an assertion might be specifiable in a language which commits one only to one’s preferred ontology, in this case o-entities. If so, what would make a t-assertion truth-valued would be a truth-condition couched in observational language. (Let us call it an o-condition.) O-conditions are, for reductive empiricists, verification conditions. So, t-assertions might be provided with verification conditions, hence become meaningful and, if these conditions obtain, even true. Such has been the big promise of the project of translatability. provide verification conditions for t-assertions without inflating one’s ontology beyond o-entities and logico-mathematical entities.

Failures of verificationism

The early Rudolf Carnap has been probably the only philosopher to take seriously the challenge of examining whether theoretical terms and predicates can be explicitly defined by virtue of observational terms and predicates. The failure of this project, as we are about to see in some detail, shows the implausibility of reductive empiricism: the meaning of theoretical terms cannot be completely defined by virtue of the meaning of observational terms.

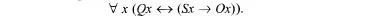

An explicit verbal definition of a (the definiendum) in terms of b and c (the definiens) has the following two virtues. First, the meaning of a is fully specified by the meaning of b and c; hence, if the definiens are meaningful so is the definiendum. Second, given a’s explicit definition, a can be systematically replaced, without loss, by its definiens in any (extensional) context. It then becomes obviously appealing to an empiricist to attempt to show that t-terms can be explicitly defined in a vocabulary which involves only observational, and hence antecedently meaningful, terms. An explicit definition of the t-term Q has the following form:

(D) states that the theoretical term Q applies to an object (or a set of space-time points) x if and only if, when x satisfies the test conditions S, x shows the observable response O. So, for instance, an explicit definition of the theoretical term ‘temperature’ would be like this. An object a has temperature of c degrees centigrade if and only if the following condition is satisfied: if a is put in contact with a thermometer, then the thermometer shows c degrees on its scale. The conditional (S → O) is what Carnap once called a ‘scientific indicator’. Scientific indicators express observable states of affairs which are used as the definiens in the introduction of a term. Early on, Carnap asserted that ‘in principle there are indicators for all scientific states of affairs’ (1928: §49).2 This already presupposes a commitment to the verification criterion of meaning. Carnap’s thought is that all theoretical terms introduced in the language of science should be meaningful, their meaningfulness being guaranteed by the availability, in principle, of scientific indicators appropriate to the definition of each and every legitimate theoretical term. But such an assertion is nothing but a hypothesis, the credibility of which depends on the verification criterion of meaning. Without the latter, there is no ground to require each and every t-term to be definable by scientific indicators. Instead, as we shall see in detail momentarily, empiricists can leave happily with the idea that t-terms are meaningful, even though they are not explicitly definable.

An unwelcome consequence of the process of explicit definitions is that if theoretical concepts are defined operationally, then we end up with a multiplicity of concepts, defined by virtue of some specific experimental set-up. So, instead of a single concept of temperature, we would end up with a great number of such concepts, depending on whether temperature is measured by an air thermometer, or by an alcohol thermometer, or by a mercury thermometer, or what have you. On an operational understanding of theoretical concepts, there is no reason to think that all these concepts correspond to the same physical magnitude since, on this account, what makes a concept what it is is an operational procedure. Different operational procedures define different concepts. After all, how can one establish purely operationally that all these definitions pick out the same physical magnitude, unless one is already committed to the view that there is such a common physical magnitude? Some radical operationalists (e.g. Bridgman 1927) chose to live with this consequence: there is not just one magnitude of, say, temperature, and merely different ways to measure it or to apply it to experiential situations. On Bridgman’s view, there is a multiplicity of different magnitudes which we wrongly characterise by a single concept: temperature. This move, however, is in conflict with sound scientific practice. It does much more justice to such practice to accept that what all these operations have in common is that they measure one and the same physical theoretical magnitude (cf. Hempel 1965). It then follows that this single magnitude is irreducible to any of those operational procedures. Nor is it reducible to a disjunction of known experimental procedures, since we should allow that hitherto unknown procedures may be devised which can be used to measure this very magnitude.

Suppose, however, that the foregoing problem is set aside. Still, if the conditional (S →O) featuring in the explicit definition is understood as material implication, then one can easily see that (S → O) is true even if the test conditions S do not occur. So, explicit definitions turn out to be empty. Their intended connection with antecedently ascertainable test conditions is undercut. For instance, suppose that we never put the object a in contact with a thermometer. Since the antecedent S of (S → O) is false, the conditional is true. It then follows from the explicit definition of ‘temperature’ that the concept ‘temperature of c degrees centigrade’ applies to a (whatever the numerical value c may be). In order to avoid this problem, the conditional (S →O) must be understood not as material implication but rather as strict implication, i.e. as asserting that the conditional is true only if the antecedent obtains. But, even so, there is another serious problem. The suggested reading of (S →O) as strict implication makes it inevitable that attribution of physical magnitudes is meaningful only when the test conditions S obtain. Yet, in scientific practice, an object is not supposed to have a property only when the test conditions S actually occur. For instance, bodies are taken to have masses, charges, temperatures and the like, even when these magnitudes are not being measured.

In order to avoid this conflict with sound scientific practice, the conditional (S →O) must be understood counter-factually, or subjunctively. Then the explicit definition of Q is understood as saying that the object a has the property Q if and only if, were a to be subjected to test conditions S, then a would manifest the characteristic response O. Theoretical terms should then have to be understood to be on a par with dispositional terms.

However, the introduction of dispositional terms, such as ‘is soluble’, ‘is fragile’ and the like, faces another bunch of problems. Their essence is that a counter-factual introduction of dispositional terms requires a prior understanding of the ‘logic’ of counter-factual conditionals, in particular of what exactly makes a counter-factual conditional true. Now that all theoretical terms have to be understood to be ultimately on a par with dispositional terms, the problem in hand intensifies. A natural way to deal with this problem is to appeal to nomological statements in order to subsume subjunctives such as ‘if a were submerged in water, a would dissolve’ under the jurisdiction of general laws such as ‘For all x, if x is put in water, then x dissolves’ and of certain initial conditions. Such a move would provide prima facie truth-conditions to counterfactual conditionals and a basis for introducing dispositional terms in general (cf. Goodman 1946). It is well known that this account of counter-factuals faces some interesting problems of its own (see Horwich 1987). But, for the issue of the explicit definability of t-terms, what it is relevant to stress is that nomological statements express laws of nature. Not only are laws of nature not observable, but also nomological statements are not explicitly definable in terms of observables (at least for non-molecular languages). Nor can the meaning of nomological statements consist in their conditions of verification, precisely because they typically range over an infinite domain. So, insofar as the project is to define t-terms in a vocabulary that involves observable terms and predicates, the counter-factual reading of explicit definitions cannot get off the ground.

Even if all of the foregoing problems concerning explicit definition were tractable, it is not at all certain that all of the theoretical terms which scientists consider perfectly meaningful can be given explicit definition. Terms such as ‘magnetic field vector’, ‘world-line’, ‘gravitational potential’, ‘intelligence’, etc. cannot be defined effectively in terms of (D), even were (D) to be unproblematic.

The futility of the project of explicit definition was asserted by Carnap as early as 1936, in his magnificent ‘Testability and Meaning’. This failure marks the end of strict reductive empiricism. If theoretical terms are not explicitly definable, then they cannot be dispensed with by semantic means. Well, one may say, so much the worse for them, since they thereby end up meaningless. Not quite so, however. Suppose one were to accept the view that theoretical terms end up meaningless because assertions involving them cannot be fully translated into assertions involving observational terms and predicates, which, one might think, can be fully verified. The problem with this supposition is that, strictly speaking, even assertions involving only observational terms and predicates cannot be verified. Hence, if verification is a guide to meaningfulness, then neither t-terms nor o-terms end up meaningful. This is the real problem with the verification theory of meaning: that even singular statements about observables are not, strictly speaking, verifiable.

When it comes to nomological statements, radical empiricists can happily accept that they are, strictly speaking, meaningless because they are unverifiable. They might choose to retreat to the inference-ticket account of law-like statements: strictly speaking, law-like statements are meaningless, but they provide the major premiss in arguments whose minor premiss and conclusion are verifiable. So, for instance, ‘All Ravens are Black’ might end up being meaningless, but we can use it as a rule of inference to infer that ‘a is Black’ from ‘a is a Raven’. Moritz Schlick toyed with this idea for quite some time.3 But even were one willing to adopt this view, verificationism still would not be home and dry. As noted above, even singular statements about observables are not, strictly speaking, verifiable. Take the statement ‘A black raven sits in the garden’. No amount of evidence will logically entail that statement. (Just consider a case of hallucination.) In other words, all evidence is perfectly consistent with the negation of the statement. Verification can never be conclusive. Hence if meaning(fulness) rests on verification conditions, then all o-assertions might well end up being meaningless too, undermining the very foundations of reductive empiricism. Carnap (1936, 1937) recognised this problem early on, and abandoned verification in favour of confirmation.

Liberalisation

What follows from the analysis thus far is that the empiricists’ criterion of meaning should be weakened. This, as we are about to see, has significant implications for the empiricists’ attitude to theore...