- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Children and Material Culture

About this book

This is the first book to focus entirely on children and material culture. The contributors ask:

* what is the relationship between children and the material world?

* how does the material culture of children vary across time and space?

* how can we access the actions and identities of children in the material record?

The collection spans the Palaeolithic to the late twentieth century, and uses data from across Europe, Scandinavia, the Americas and Asia. The international contributors are from a wide range of disciplines including archaeology, cultural and biological anthropology, psychology and museum studies. All skilfully integrate theory and data to illustrate fully the significance and potential of studying children.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Children and Material Culture by Joanna Sofaer Derevenski in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Archaeology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I Theoretical perspectives

Chapter 1

Material culture shock Confronting expectations in the material culture of children

Joanna Sofaer Derevenski

CHILDREN AND CONTEXTUAL CONTINGENCY

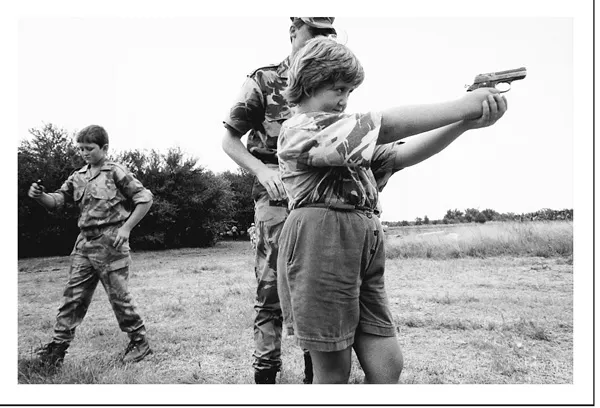

Figure 1.1 A week in the life of the ‘new’ South Africa Source: Photograph: Ian Berry, Magnum Photos

Sometime after the end of apartheid in South Africa, a photograph of a young girl dressed in an oversized camouflage shirt and shorts and holding a handgun appeared in the British press (Figure 1.1). Next to the picture, an accompanying article described how some Afrikaner children were being given military training. It also expressed shock and concern. The photograph and article provoked further comment in editorials and in the letters page. Why does the image and idea of a child with a gun have such a powerful effect upon the observer?

The photograph is a record of a real contemporary event, rather than the fiction of a book or film. The child is not playing; the gun is a lethal weapon, the girl is being trained to kill. The photograph creates a disjunction between the encultured expectations of the modern Western reader and material reality. Connections which we hold with concepts of ‘child’ (innocent, passive, protected, happy and young) and ‘weapon’ (worldly, aggressive, violent, suffering and adult) are mutually exclusive oppositions. The juxtaposition of a child with a lethal weapon creates incongruity; the material culture of the gun ought to be held in a different hand, the uniform of battle should be worn by another body. Further disruption is caused by a female holding the gun as weapons are deemed male objects (McKellar 1996). We conceive of children as apolitical, yet here the girl appears involved in adult intrigue. For all these reasons, conceptual associations between the child and the material culture do not match.

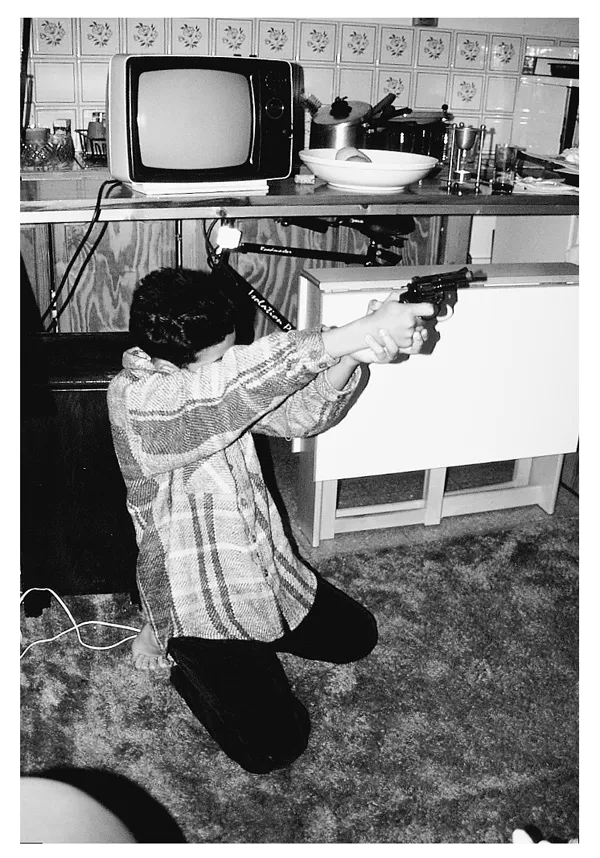

Figure 1.2 Child playing Source: Photograph: Joanna Sofaer Derevenski

Yet, ultimately this photograph conveys very little about the child as an individual person. No autobiography or description of her daily life is attached to the image. We know nothing of her personal history and will almost certainly never meet her face to face. Our perception of the child and her life is formed through the relationship between the child and the material culture in the photograph, itself a form of material expression. Our knowledge about the events leading up to the photograph and those that followed it is constructed through the accompanying text rather than through the image. In highlighting the gap between expectation and reality, this photograph confronts us with our own expectations regarding children and material culture and forces reconsideration of what it means to be a child.

Perceptions of children and the particular forms of material culture with which they may be observed are deeply affected by context and the wider material environment in which they are situated. Ostensibly similar forms of material culture to that used by the Afrikaner child in a military setting are readily provided for children in a domestic milieu (Figure 1.2). Guns sold in the local toy shop are often made of similar materials (metal and plastic) and are of comparable size to their deadly counterparts. Without detailed inspection of the object, the cellophane and cardboard packaging are often the primary clues that the former should be presented as toys. Yet, within the home, perceptions of the child and the material culture of the gun seem less disturbing. In this context the child conforms to our expectations: children, rather than adults, ought to use toys. The threat of genuine violence is removed. If a male holds the gun then gender expectations are confirmed. The child’s interaction with the object is classified as play, an activity to which no political motivation is attributed. The understanding of the material culture is closer to our own experience and conceptual associations between the child and the material world seem appropriate.

Children have often been sentimentalised (Cox 1996; James et al. 1998). Research like that of Opie and Opie (1959, 1969, 1993) on nursery rhymes and games has become the popular face of child life. In researching the material imagery of the life course in photographic libraries and archives, I found searches under the heading ‘children’ overwhelmingly yielded images of smiling children playing with dolls, blocks or other toys, children in parks or naturalistic settings, children with pets, naked children, gurgling babies or humorous pictures of children posed growing in flowerpots or on the toilet. The classification of these pictures clearly draws on conceptualisations of the child as happy, innocent, natural, immature, uninhibited, amusing and sweet. Less pleasant images of children were often classified according to the country in which the photograph was taken. Thus, while a child may be the primary subject of a photograph, if the picture lacks ‘cute factor’ the child is reduced to an ethnographic curiosity.

Ennew (1986) argues that Western childhood has become a period in the life course characterised by social dependency, asexuality and the obligation to be happy, with children having the right to protection and training but not to social or personal autonomy. The corollary to this is that power relations are weighted in favour of adults (James et al. 1998; Qvortrup et al. 1994). Being a child is to have a particular place in the social order. To step outside those relational boundaries and be a child outside adult supervision is to be out of place (Connolly and Ennew 1996). The Afrikaner child appears to have reversed the social order, even to the extent of posing a threat to adults through the possession of a weapon. She has obtained power through the materiality of the gun.

In popular and academic circles, there is growing concern that children are losing their childhood (Scraton 1997a; Cox 1996; Winn 1984). High-profile cases of paedophilia or the murder of children by other children, such as the murder of 2 year old James Bulger by two 10 year old boys in Britain, and a spate of school shootings in the United States, have dismayed and bewildered (Hay 1995; Egan 1998). How could adults do such repellent things to defenceless children? How could children commit such crimes? There is at once a need to protect children yet simultaneously to demonise them (Davis and Bourhill 1997). Thus, being a child is not simply defined by age and power relations, but is also experiential.

Experience is also defined by materiality (Cole et al. 1971; Sofaer Derevenski 1994, 1997a). Recent research on the impact of the war in the former Yugoslavia in which children were invited to write life-history essays (Povrzanovic 1997) reveals within the repeated theme of loss of childhood an acute awareness of how being a child is affected by the material environment. Similarly, an 11 year old caught up in the siege of Sarajevo wrote in her diary of her fear, loss of innocence and despair, and of her life without school, fun, games, friends, nature and sweets (Filipovic 1994). These she perceived to be the material ingredients of childhood (Cunningham 1995). Deprived of them she and her friends can’t be children (Filipovic 1994; Cunningham 1995). For her, ‘a child was not simply someone aged between, say, birth and fourteen; a child could be a real child only if he or she had a “childhood” ’ (Cunningham 1995: 1). In the case of Croatian children, the material culture of war was employed in the reproduction of their lived realities, providing a form of catharsis (Povrzanovic 1997; Korkiakangas 1992).

If being a child is constructed through material experience then, returning to the image of the Afrikaner child with a gun, one is suddenly faced with a series of questions: She looks physiologically like a child, but is she a child? Are her experiences those of a child? Does she have a childhood? Is she a child because she has no control over her actions and is being indoctrinated or manipulated? The social and moral issues raised by this picture are paralleled by important questions from an archaeological point of view: Given that the gun is clearly being used by the child and is part of her material reality, is it then a material culture of children? If so, does it also form part of a material culture of childhood or does the weapon represent its loss? Is a toy gun the real material culture of children? Is it the material culture of childhood? Is there more than one way of being a child and more than one childhood, each of which are equally as valid, if perhaps not as pleasurable, as another?

CHILDREN AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL CONTINGENCY

Given the importance of context in constructing the materiality of children’s lives and in determining the ways in which children and material culture are perceived, how are arte-facts and more particularly weapons, interpreted when found with children in the past? The clearest examples of associations between children and weapons are in mortuary contexts. Furthermore, some of the boldest and most influential statements concerning the interpretation of children and material culture have been made regarding these settings.

Weapons are frequently identified as symbols of power and masculinity (Bradley 1990; Treherne 1995). In cases where such artefacts are deposited with both selected children and adults, or where they are given similar forms of burial, this is construed as strong evidence for inherited status and wealth (e.g. Peebles and Kus 1977; Whittle 1996; Lillie 1997; Welinder 1998); ‘it is usually suggested that as the children died too young to have actually earned the right to the objects on their own merit, the objects must have been placed there by the parents whose positions the children would have inherited had they lived’ (Pader 1982: 57 cited in Crawford 1991: 18). Brown (1981) identified the mortuary treatment of children as a key indicator of the relationship between social and demographic variables; ‘as the hierarchical aspects increase, children will be accorded more elaborate attention in proportion to the decline in the opportunity for replacement of the following generation’ (ibid.: 29). In cases where children are exclusively buried with particular artefacts, or conversely, are the only individuals deposited without them, this is understood in terms of horizontal differentiation and the construction of difference between age groups (Chapman and Randsborg 1981; O’Shea 1984; Richards 1987; Morris 1992).

These principles have often been key to the analysis of children and material culture in archaeological contexts. For example, O’Shea (1981) studied the distribution of artefacts in two Arikara sites in the central plains of North America – the mid-eighteenth century Larson cemetery and the early nineteenth century Leavenworth cemetery. Along with other artefacts, the occurrence of gun parts in the graves of sub-adults at Larson was identified as evidence for the ritual expression of social differentiation between adults and sub-adults, as well as ranking within the sub-adult category. By contrast, at Leavenworth the distribution of gun parts was less restricted. This change in artefact distribution was understood in terms of a temporal de-ritualisation of mortuary practice with a shift towards increased emphasis on individual and family economic power (ibid.). In this case, weapons with children are first understood as mediators of ritual and then as an index of the wealth of older individuals who, by association, transfer their power to younger ones. Simply by virtue of being ‘children’, the young cannot be identified as powerful in their own right. Objects in child graves are interpreted in a fundamentally different way to the same arte-facts with adults.

The graves of Anglo-Saxon ‘warrior children’ (Gilchrist 1997: 47) contain weapons including arrowheads, spearheads, swords and shields. However, not all Anglo-Saxon children were buried with such artefacts; in a sample of forty-seven fifth to seventh century English cemeteries, Härke (1992a: 183, figure 33) found that only sixty out of 382 graves classified as neonates, infants I or II and juveniles on the basis of skeletal immaturity were weapon burials. A far higher proportion of adults were buried with weapons; 231 out of a total of 511 graves. The frequency of child graves containing weapons, the number and type of weapon deposited, and the length of spears and knives appear to be related to age at death (Härke 1992a, 1989). The data derived from the study of the children’s graves forms an important strand of evidence in Härke’s interpretation of Anglo-Saxon mortuary practice. He suggests that the deposition of weapons in both child and adult burials was primarily a symbolic act which recognised the social or ideological hereditary ‘warrior status’ of an individual, independent of the experience or ability to fight (Härke 1990, 1992a, 1992b; Gilchrist 1997). The inclusion of arms in the burial may have been partly dependent on the completion of rites of passage (Härke 1992a; Pader 1982). Crawford (1991) points out that 10 years was the legal age of adult responsibility in the seventh century. However, Härke (1990, 1992a) suggests that the primary determinant of weapon burial was descent and ethnicity. Thus, the graves of children with weapons are used to explore the broader social structure of the Anglo-Saxon period.

Such far-reaching interpretations of children and material culture often seem to dissolve when small or miniature weapons are found with children. For example, the miniature spearhead found in the grave of an infant at the La Tene I site of Vrigny, France (Champion 1994) has been interpreted as a toy (Chossenot et al. 1981). Similarly, a sword, spear and frying-pan from a Vendel grave in Leirol, Norway (Selboe 1965; Linderoth 1990), and miniature daggers and a spearhead from Birka (Gräslund 1973) have been reported as toys. Indeed, in cases when osteological analysis cannot be carried out, small objects are sometimes used to infer the presence of a child (Gräslund 1973; Hodson 1977).

These interpretations are based on the assumption that since children are by definition smaller than adults, only children interact with small objects. Furthermore, in modern Western society, children are implicitly regarded as passive; people who play rather than contribute socially or economically to society. Hence the archaeological value ascribed to a miniature object is minimised and its identification as a toy relegates the significance of the artefact to the level of curiosity. The identification of an object as a toy is rarely related to social significance or meaning. It is rather a morphological description constructed on the basis of the artefact’s size and material (Lillehammer 1989) which presupposes the same cultural values as those held in our society. However, the functional identification of an object as a purpose-built toy is a complex task (ibid.; Egan 1996). We often forge...

Table of contents

- COVER PAGE

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT PAGE

- CHILDREN AND MATERIAL CULTURE

- ILLUSTRATIONS

- CONTRIBUTORS

- PREFACE

- PART I: THEORETICAL PERSPECTIVES

- PART II: REPRESENTING AND PERCEIVING CHILDREN

- PART III: THE TRANSMISSION OF KNOWLEDGE

- PART IV: CHILDHOOD LIVES

- PART V: CHILDREN AND RELATIONSHIPS

- PART VI: GEOGRAPHIES OF CHILDREN

- PART VII: CHILDREN AND VALUE

- PART VIII: DEMOGRAPHY AND GROWTH OF CHILDREN