- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Reflecting On School Management

About this book

The reorganisation of the education system within Britain has vastly increased the managerial responsibilities of those working in schools, although the staff generally have received little management training. In this book, the various issues related to management are teased out and a selection of ideas and pragmatic solutions informing good practice are examined.

Trusted by 375,005 students

Access to over 1 million titles for a fair monthly price.

Study more efficiently using our study tools.

Information

Topic

EducationSubtopic

Education GeneralChapter 1

Philosophy and Values in Education

Management

This chapter introduces some ideas and questions which give strength and support to explorations of school management by setting them within an ethical dimension. Throughout the chapter, there is a comparative and international perspective that we would like to introduce as a sub-theme throughout the book.

Key issues for managers:

- The importance of the articulation of underlying principles;

- The need for an ethical approach to management in education;

- Issues of democracy, choice, power and equal opportunities;

- Managing current contexts according these principles.

Educational Principles and Values

The Collins English Dictionary (1990) defines ‘ethical’ as:

adj. 1. of or based on a system of moral beliefs about right and wrong. 2. in accordance with principles of professional conduct.

These two definitions link an understanding of right and wrong with notions of professionalism. Teachers are sometimes uncomfortable about the use of the term ‘professional’ in relation to their work. For some, it signifies a depth of reflection and understanding about taking responsibility for the activities of learning and teaching which is underpinned by years of involvement in and commitment to education. In other words for them, each action taken and all decisions made about every aspect of learning and teaching are based on a clearly articulated set of ethically based beliefs and understandings about the purpose of education.

Other teachers remember with discomfort what Grace (1987) calls ‘the legitimated professionalism which emerged in the 1930s’. This professionalism

involved an understanding that organised teachers would keep to their proper sphere of activity within the classroom and the educational system and the state, for its part, would grant them a measure of trust, a measure of material reward and occupational security, and a measure of professional dignity. (p. 208)

For these teachers, a mistrust of the term ‘professional’ comes from what they see as a historical narrowing and limiting of their sphere of action. For many years after the 1930s, this narrowness seemed to disappear to reflect more the first definition of professionalism. But the Education Reform Act of 1988 was initially so prescriptive that it made teachers begin to question once again British society’s expectations about their autonomy and professionalism. Does a truly professional body work to such clearly externally prescribed guidelines? It remains to be seen where the British government and British society of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries position teachers. Who will continue to decide what is taught in British schools and how it will be taught? Whose values and ethics will teachers be working with in schools?

At present, the Department for Education and Employment (DfEE) expects that schools will include a statement about their educational values in their documentation. They may call it their mission statement, or the school’s vision of education, their values statement, their beliefs about education, their school’s statement of purpose or their school aims. However they describe it, it is that which makes each school different from any other, but only if it is put into operation within and around the school. In other words, the managers of a school have a responsibility to see that the values stated are implicit in every activity that takes place in the school. For example, many schools include in their statement such phrases as ‘enriching’ or ‘achieve potential’ or ‘recognizing and celebrating differences’. Are these values communicated clearly to a visitor or a stranger walking round the school? Chapter 2 explores this issue in more detail, and follows on to show how the school’s declared purpose will be agreed and clearly articulated, so that the published purpose informs the culture of the school. Here, however, it is important to note that a statement of principles or values from each school is expected by law.

In what way are these values ethical? What is the connection between values and ethics, and why must those who manage schools ensure that their management decisions have an ethical basis? Robert J.Starratt (1996) writes:

While it includes conversations with individual teachers, the larger work of administration involves calling all the teachers to the building of an ethical school. This involvement provides the administrator and the teachers with a large moral task, one that will never be finished, but one that will enable them to integrate many of the specific moral and professional components of teaching into a larger, meaningful whole. One might benignly interpret all or much that teachers presently do as tacitly involved with nurturing an ethical school. In the best of schools that may certainly be true. I suggest that they do this work more intentionally, discussing explicitly the fundamental components of the task and seeking through explicit programmatic elements to offer an intentional environment for moral learning. (p. 156)

Starratt builds up his argument by explaining that ethics is the study of moral practice, and as a scholarly inquiry ‘ethics tends to dissect human actions, thinking, and choices in order to understand when they are ethical or unethical’. Thus, those who are involved in ethical school management, and the management of ethical schools, must ensure that there are spaces for reflection, for conversations and for planning during the school day. These spaces will offer teachers the opportunity to ‘study’ and think about practice, in order to plan consciously for ethical interactions.

There is a danger in schools that those working in them take for granted that there is only one true set of values. Bottery (1992) writes:

values may be contested within an organization, and values not necessarily in accord with those passed down the hierarchy may be adopted and practised by those within the organization. Values, then, cannot be simply held as objectively correct, but are adopted for particular purposes by particular people or groups, and are therefore contestable. (pp. 180-181)

This quotation raises an interesting management question: a principled school manager may believe that those who work in the school should have space to develop and work with their own educational values. But the same manager is committed to embedding the school’s published purpose in all that happens there—how might the different sets of values be mediated? Or indeed, is there room for different sets of values in one educational organization?

It might be helpful here to think about the values underpinning the organization in which you are working. The following set of questions could be answered in conjunction with the questionnaire in Chapter 2, in which it is suggested that the school ethos reflects the values of the school.

Activity

Tracking the Values System within a School

First attempt to answer the following questions alone, and then, if appropriate, compare your answers with those of a colleague within your school with whom you believe you share values.

- Without reference to any school literature or publications, write down what you remember of the school statement of values.

- Check what you have written with the statement published in literature about the school.

- What do you think a senior manager in your school might write if asked the same question?

- What do you think a very new teacher might write if asked the same question?

- What do you think a pupil would answer?

- What might a parent say?

- What would a member of support staff in your school say?

- And what might a visitor to the school say after spending half an hour on the premises?

If the values in a school are clearly shared and articulated, then most of the answers to the above questions would be the same. All the constituencies with a stake in the educational organization will have had an input into the formation of the statement, and will have contributed to its regular review, or will have made a conscious choice to be involved in the organization because the statement matches their own values.

If, however, they are not shared, the answers may be very different. And does this matter? If, as Bottery (1992) writes, values may be contested within an organization, how might different contexts affect their articulation of values in one organization?

Ethical Dimensions to School Management

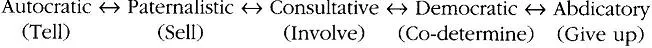

One arena in which values are clearly affected by different contexts is the management or leadership style employed by the headteacher and other managers. This is examined in greater detail in Chapter 3, but in order to begin to explore the links between leadership and values, here is a very simple summary of a continuum of leadership styles. Based on the ethical beliefs of the headteacher, it might encompass the following ways of managing:

In order to help make sense of this continuum, you might think about your own management style and about your response to the management styles of others.

Activity

After thinking about your own understanding of management values, place yourself on the continuum above, then answer the following questions:

- Which style(s) do you respond to?

- Which style encourages teamwork?

- Which style is nearest to your own dominant styles?

- Are leaders always consistent in their styles? If not, why not?

The answer to the fourth question left will probably include such circumstances as:

- it depends on the task to be managed;

- it depends on who is to be managed;

- it depends on the understanding and commitment to the task of those who are to be managed;

- it depends on the resources;

- it depends on external demands;

- it depends on the time allowed to manage the task and

- it depends on the educational and management principles of the manager.

It is probably true, however, that apart from the times when autocratic management is imperative (such as in times of immediate danger, when commands are non-negotiable), most leaders hover around one point on the continuum whatever answers they come to. They may waver depending on the answers above, and may at times feel driven towards managing in an alien style, but their fundamental beliefs about the purpose of education will inform the basic choice of leadership style. For example, a leader who believes absolutely in democracy and empowerment in education will work as often as possible in a democratic way with other teachers and members of the school, encouraging them, perhaps, to develop and use an informed voice in decision-making.

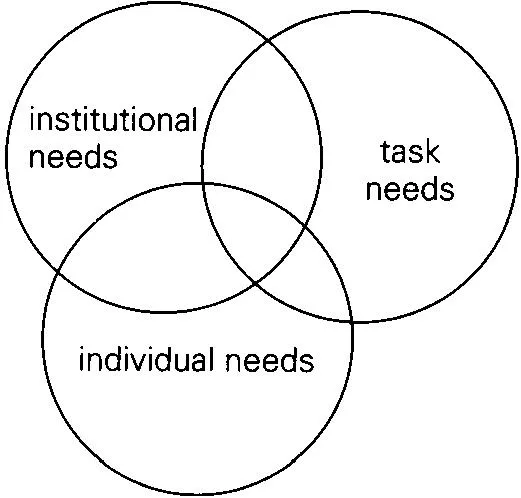

In this way, a headteacher who believes that all needs in the school community should be balanced as carefully as possible will base management decisions on the diagram introduced by John Adair (1986) (Figure 1.1) in which he shows that teams work best when attention is paid equally to three sets of needs:

Figure 1.1: Effective teambuilding

Source: ADAIR, J. (1986) Effective Teambu ilding, Reading: Pan

Should one set of needs—say an individual teacher’s need—overpower the needs of the institution or the task, the task of education within the school will not easily be achieved. Should the demands of the task overshadow the needs of individuals within the school, there will be depression, stress and general disquiet. And should the needs of the institution take precedence over the needs of the individual and the task, unhappy teachers will not be able to ensure that the young people in the school are receiving the education that the school has stated as its purpose. The initial recognition of the necessity to balance the needs, and then the definition or measure of the different balances will all depend on the headteacher’s educational and management values, and therefore the management choices made. To what extent does the definition of balance—the power to encourage such decisions about a school and its values—reside with the headteacher?

Leadership, Power and Values

Hodgkinson (1991) argues that although a leader has structural or executive power coming from the formal legal structure, ‘power in another sense always rests ultimately with the individual components of that structure’ (p. 80). He goes on to say that those people who are managed can find ways of refusing to do what their manager wishes them to do—they can always quit, walk away or sabotage. And he writes that part of a leader’s skill is to be able to persuade followers to follow. These leadership skills are the ones he sees as political skills:

The intimate connection between power, political power (itself a value), and the resolution of common problems emphasizes the necessity for the educational leader to have political skills and to be, in part at least, a politician. This in itself, of course, entails no guarantee of ethical responsibility; it only recogniz...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- List of Figures and Tables

- Series Editor’s Preface

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Philosophy and Values In Education Management

- Chapter 2: What Is Management In Education?

- Chapter 3: Management and Leadership Styles

- Chapter 4: Working With People, Part One— Management Skills

- Chapter 5: Working With People, Part Two Developing Staff

- Chapter 6: Managing In the Market Place

- Chapter 7: Managing Finance and Resources

- Chapter 8: Managing Across the Boundaries

- Chapter 9: Curriculum Management

- Chapter 10: Managing In Turbulent Times

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Reflecting On School Management by Jennifer Evans,Anne Gold in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.