Constructions of childhood and youth encompass both descriptive and normative elements: the characteristics attributed to young people of different ages and sexes, how they are treated, the ways they are expected to behave, how they are valued by society and what is considered desirable in a young person. Western ideas about childhood and youth have shaped policies and practices, not only in the West, but also in former European colonies, in the international arena and in development interventions. There is, however, no singular coherent Western conceptualisation of either childhood or youth, but rather a number of discourses that are often seemingly contradictory and have their origins in different historical contexts.

Childhood

Particular conceptualisations of childhood need to be understood in relation to the social conditions that gave rise to them (Heywood 2001). For instance, when many children died at an early age, less investment was made in young children, either economically or socially. Indeed, infant mortality was first calculated in the late nineteenth century, although the data this required had long been available (Aitken 2001). Older children were accorded greater value, in part for the economic contributions they made to impoverished households. In the minority world today, in contrast, ‘[c]hildren have become relatively worthless economically to their parents, but priceless in terms of their psychological worth’ (Scheper-Hughes and Sargent 1998, 12). Social conditions do not arise from a vacuum, however, but relate to wider economic and political processes. It has been argued that hardening of the child/adult dichotomy was central to the development of modern capitalism and modern nation states (Stephens 1995).

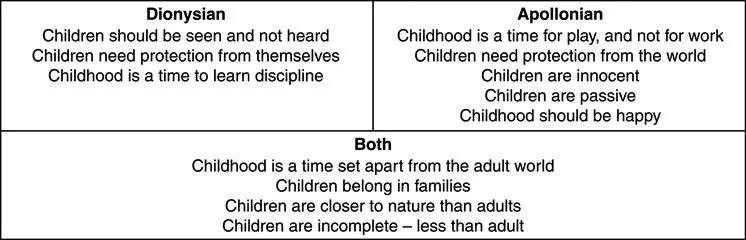

Figure 1.1 Western concepts of childhood: legacies of the Dionysian and Apollonian views

Although concepts of childhood may be related to prevailing conditions, there have long been ambiguities in the ways in which children are understood in Western thought. To a large extent, concepts persist beyond the conditions giving rise to them, and Heywood (2001, 20) has urged us to ‘think in terms of … competing conceptions of childhood in any given society’. Over the past four centuries in the West there have been two predominant yet contradictory images of children, characterised by Jenks (1996) as ‘Apollonian’ and ‘Dionysian’ views (Figure 1.1). Although both views have long roots, the Dionysian view is said to have dominated in the West prior to the twentieth century, but that increasingly the Apollonian image came to the fore, particularly influencing society’s views concerning younger children. Both are somewhat problematic (Holloway and Valentine 2000) and oversimplify sets of disparate ideas, but remain influential today.

The Dionysian view perceives children as ‘little devils’, born into the world with, according to Catholic doctrine, original sin, and in need of strict moral guidance (Jenks 1996). Children are seen as impish pleasure seekers who are easily corruptible and may be led into bad habits unless they are kept occupied and strictly disciplined. At a time of high infant mortality, discipline was needed to save children from themselves, to ensure their redemption and place in heaven (Holloway and Valentine 2000). From seventeenth-century Puritanism to the childhoods described by Dickens in the nineteenth century, the Dionysian view inspired injunctions not to ‘spare the rod and spoil the child’. Even today, the idea that children should be kept away from certain places and protected from ‘dysfunctional families’ is fed by the idea that such conditions may serve to liberate the demonic forces already present in the child (James et al. 1998). Allowing such evil forces to be unleashed would threaten not only children themselves, but also wider adult society (James et al. 1998). Fear of the ‘polluting’ effect of disruptive and anti-social children informed social policy in Victorian Britain (Boyden 1990), and arguably influences policy responses to majority world children today.

By contrast, the Apollonian view casts children as ‘little angels’, born innocent and untainted by the world. Rather than needing to be beaten into submission, the Apollonian child is naturally virtuous and needs encouragement and support (Jenks 1996). Children are viewed as special; needing protection, not from their own inner weakness, but because their intrinsic natural state is desirable and worth defending (James et al. 1998). While this perspective is apparent in the eighteenth-century writings of Rousseau, particularly Emile (James et al. 1998), its growing prevalence in the West is often characterised as a middle-class sentimentalisation of childhood, partly rooted in adult nostalgia (Boyden 1990). It too has had practical implications. The Apollonian view sees children as individuals, more than as a collective future adult society or an integral part of contemporary society, and has come to dominate Western ideas about how children should be treated, both by society in general, and within specific contexts of, for example, home and school (Jenks 1996).

These twin perspectives on children are apparent in many of the characteristics popularly attributed to childhood. The idea that childhood should be a time set apart from the adult world is rooted in an Apollonian notion of children as different and special. This idea began to emerge among the wealthy in eighteenth-century Europe (Ariès 1962), but in the nineteenth century many still believed children should be occupied in hard labour for their own good and that of society: that children’s natural idleness should be disciplined. The Western view that childhood should be happy, a time devoted to play and learning rather than work, is thus relatively recent.

While the Apollonian and Dionysian perspectives are clearly contradictory, they are not wholly unrelated. Both see children as closer to nature than adults: either as ‘savage’ and in need of taming, or as pure and in need of nurture (Jenks 1996). Both views consider children fundamentally different from adults. Ariès (1962) pointed to the increasing physical segregation of children from adults. Both Dionysian and Apollonian fears have led to children’s progressive removal from ‘adult’ public space, retreating to either designated children’s spaces or the home (Holloway and Valentine 2000). Equally, children are seldom accorded a public voice. The notion that children should be ‘seen and not heard’ illustrates adult society’s disregard for children’s opinions. Children came to be seen as incomplete – passive recipients of adult care and tuition, rather than agents in their own lives, let alone in wider society. They have belonged to families, with their families acting on their behalf and representing their interests.

Children in the West were described in 1975 as ‘being seen by older people as a mixture of expensive nuisance, slave, and super-pet’ (Holt 1975, cited in James et al. 1998). In the early twenty-first century, Western childhoods are described in predominantly Apollonian terms. Victorian childhoods are now regarded as excessively harsh and society is supposedly more child-centred. However, the media focus on children’s innocence and vulnerability bears little relation to the real lives and interests of young people, even in the West. Subject to an increasingly different set of rules from adults, ‘[c]hildren can no longer be routinely mistreated, but neither can they be left to their own devices’ (James et al. 1998, 14).

A series of discourses describing the needs and characteristics of children has become conventional wisdom. Significantly, these discourses ‘begin from a view of childhood outside of or uninformed by the social context within which the child resides’ (James et al. 1998, 10). Viewing childhood as a natural state has contributed to a tendency to universalise Western concepts (Jenks 1996), assuming they apply equally to non-Western contexts. However, the childhood characteristics that are common currency in the discourse of Western media and public policy only partially relate to Western childhoods as lived today (or even in the past). They deviate sharply from the experiences of many majority world children. As will be discussed further, they are nonetheless powerful in their impacts on development policy and practice, and their traces appear in media representations of majority world children (Burman 2008).