Chapter 1: Doctoring individuation

Gregory House: Physician, detective or shaman?

Luke Hockley

Introduction

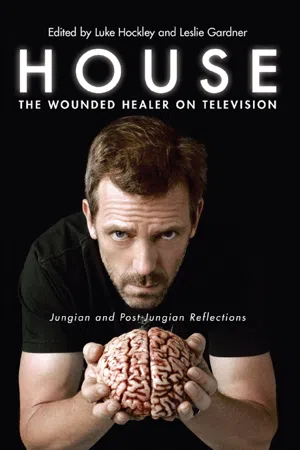

Gregory House (Hugh Laurie) is both a gifted diagnostician and an unpleasant human being. He is also curiously likeable. Indeed Hugh Laurie (despite the change in accent and the newly acquired walking stick) is now seemingly inseparable from his character in House. He has become a somewhat improbable heartthrob, at least so far as UK viewers are concerned, where he is better known as a comic actor from television series such as Jeeves and Wooster (1990) and Blackadder (1982/3).

Nonetheless, in 2005 the US publication TV Guide labelled him one of ‘TV's Sexiest Men’ (5 June 2005) and in 2008 he came second on the list of sexiest television doctors ever, just behind ER's Doug Ross (George Clooney). But not everyone is a fan of Gregory House, perhaps because he embodies contradictions. As this volume shows it is almost as though his internal divisions manifest themselves in the opinions of viewers and theorists alike.

This tension is encapsulated rather neatly in another headline from TV Guide: ‘House, the man you love to hate’ (17 April 2004). In the Jungian world opposites run into each other and unconscious projections run rife. House is a figure who embodies both the best and the worst aspects of being a doctor. Sometimes he saves lives, and at other times he is almost complicit in his patient's death. He is what is sometimes called a ‘wounded healer’ both literally and metaphorically. Indeed this chapter is going to suggest that to understand the complicated appeal of House we need to see him as a complicated character rooted in a range of different literary, filmic and anthropological traditions. As a doctor he is part detective and part shaman and it is this proximity to the shadow and the unconscious which is both appealing and frightening.

However, little is served by trying to come up with a ‘balanced’ view of Dr House. That enterprise would be thwarted by his contradictory nature and end up being merely an attempt to allay our own fears that something unconscious is at play. Instead I want to suggest that it is not that we are seeking to come to a reasoned interpretation of who this Dr House is, but that Dr House can more fully be understood as someone who experiences life as an individuated person. Not perfect, but whole. Not pleasant, but the person he is. As the subject of analysis, he does not need to be reined in or pinned down with the appropriate archetypal tag, such as ‘wounded healer'. It is precisely because there are unpalatable forces at work that temptation to neuter the unconscious with neat archetypal terms should be resisted. Instead we, along with the 16 million American viewers that this show attracts each week, are better off savouring the contradictions.

What is individuation?

One of the many distinctive contributions to the psychology of the individual made by Jung is the idea of ‘individuation'. Jung positions himself quite differently to Freud who came to the view that psychological disturbances in adult life were always the result of unresolved difficulties from childhood. Jung thought this was at best partial and at worst inaccurate. Instead, Jung wanted to re-orientate the psyche and rather than constantly looking back to childhood he thought it was important to examine the current situation. Why look into the past when there is every possibility that the current situation will contain enough material to tell the therapist what is happening for the client? Jung thought that there was no need to overly complicate the matter.

Along with this emphasis on the present moment, Jung's view was that the psyche was teleological, which is to say that it has a goal. He suggests that the aim of every human is to live to their fullest potential and to become completely the person they are. This is not an easy undertaking as family, friends and society all have views about how we should behave. So at its simplest, individuation involves just aging and letting the body grow old and eventually die. However, the complexity arrives when we try to understand what it means for us to live in a personal and unique manner within this context, since it makes the contradictions between our individual psychology and collective expectations explicit.

Individuation is also a psychosomatic concept, linking the unconscious with the body. This link is important since it is a theme that we are going to return to as we consider both House, the television series, and Gregory House, the man. Jung puts it as follows:

In so far as this process [individuation], as a rule, runs its course unconsciously as it has from time immemorial, it means no more than that the acorn becomes and oak, the calf a cow, and the child an adult. But if the individuation process is made conscious, consciousness must confront the unconscious and a balance between the opposites must be found. As this is not possible through logic, one is dependent on symbols which make the irrational union of opposites possible.

(Jung 1952: para. 755, emphasis as original)

As a diagnostician Gregory House is concerned with the health of the body and in making sure that it can run its course. His medical interventions are designed to restore the body to a state of health and as such we conceive of him as someone who supports and assists in the biological aspects of individuation. However, as we will see, House's evolving personal psychology, or his process of individuation, gets mixed up with the treatment of his patients – indeed this unconscious aspect of his psyche is crucial in coming to a view about why he treats patients as he does, and how he interacts with both his immediate team and the hospital in general.

The interweaving of the personal and the social is significant for while individuation is a personal matter it also has broader collective and cultural aspects. Jung suggested that to undertake the work of individuation was to place the need for personal authenticity over and above cultural norms and expectations. There is a catch here. Jung seems to be suggesting that the only way to be fully the person you are is to reject the social conventions and etiquette of the day. Yet this interpretation of matters is only partly true. What Jung is really driving at is that individuation requires that we are conscious in broader contexts about the choices that we make. In making these choices we are inclined to privilege our inner preferences, even if they fly in the face of what society regards as ‘normal’ or acceptable behaviour. In so doing we opt for authenticity over social or cultural expectation and personal need over social conventions. The downside to this is that the comfort of the collective, the easy life of fitting in and going with the flow, is abandoned in favour of the personal struggle to be fully ourselves. For Jung, this call to individuation is a vocation. Indeed, Jung thought that when the individuation process was made conscious it took the form of quests, heroic tasks, labyrinths and other maze-like forms. He comments:

The words, ‘many are called, but few are chosen’ are singularly appropriate here, for the development of personality from the germ-state to full consciousness is at once a charisma and a curse, because its first fruit is the conscious and unavoidable segregation of the single individual from the undifferentiated and unconscious herd. This means isolation, and there is no more comforting word for it. Neither family nor society nor position can save him from this fate, nor yet the most successful adaptation to his environment, however smoothly he fits in. The development of the personality is a favour that must be paid for dearly.

(Jung 1934: para. 294)

Clearly Gregory House is not overly concerned with the niceties of everyday social interaction. His numerous ‘House-isms’ encapsulate his frustration with the demands of patients and colleagues alike to moderate his behaviour to a social norm: ‘Everybody lies,’ House opines (Pilot, 1: 1), and again, ‘Normal's not normal’ (Autopsy, 2: 2), and ‘Guilt is irrelevant’ (House Training, 3: 20) and ‘Lies are like children: they're hard work, but it's worth it because the future depends on them’ (It's a Wonderful Lie, 4: 10), to cite only a few examples.

The point is that individuation does not offer a model of personal perfection, rather it is more usefully thought of as an ongoing life process in which the challenge is to make conscious the unconscious as a particular individual is driven to do. Jung stressed that individuation was not about losing our imperfections, rather he thought it was about ‘wholeness’ which for him involved not eradication of imperfection but rather its acceptance. We can go further. Individuation does not offer a paradigm for psychological health, it is not about being free from complexes or fantasies. Rather it offers a way of being in the world, a way which others might find threatening, distasteful or bizarre. Put another way, the challenge of individuation is to find a personal myth, a way of understanding how we want to live in the world. Like it or not, it seems clear that Gregory House has found his personal myth.

The body – the unconscious and disease

Jung's model of the psyche is a psychosomatic one, making it a good fit for my proposal about House, i.e. that it is a drama about the interplay between medicine and personal psychology. Of course there are other narrative tropes and inflections at play. House is also partly about the institutional politics of a large hospital. It explores the role and power of individuations in such an organisation, from the Executive Board down. But sitting underneath all this, or we might say at the centre of all this, is Gregory House – it is his psyche, his way of thinking and behaving, which permeates the series.

As mentioned, individuation is the lifelong process of bringing unconscious contents closer to consciousness with a view to living a more authentic and fulfilling life. Jung hypothesised that underlying this process there were a series of psychological structures which regulated how individuation would unfold, and he called these ‘archetypes'. Archetypes can roughly be thought of as analogous to psychological genes. They are partly inherited and partly arise from the circumstances of our upbringing. Another way of thinking about them is to regard archetypes as a predisposition to behave and to conceptualise the world in certain ways.

Archetypes influence all aspects or our lives. For example, they impact on how we present ourselves and how we try to fit into society, what Jung called the ‘persona’ – the archetype of social adaptation. Similarly our gender identity arises from the interplay of the ‘contrasexual archetypes'. In essence this is the idea that our biological sex should not limit our access to ways of being which tend to be culturally prescribed in terms of femininity and masculinity. Contrasexuality suggests that everyone has access to a much fuller range of human gendered sexuality than culture generally allows. Jung outlines numerous other archetypal patterns, noting that often archetypes appear in clusters or groups with one prefiguring the other. This notion of underlying patterns is a useful consideration as it moves us away from thinking about individuation as a linear process predicated on a series of steps. Instead it is more productive to see individuation as something ‘messy’ with different archetypes and aggregates of archetypes coming into consciousness at different times over the course of an individual's life. The question of what might be going on ‘archetypally’ in House is something we will get to in a moment.

But first the perennial question about archetypes: if archetypes such as the contrasexual archetypes are invisible then how can their presence be deduced? Jung had two related answers to this problem. The first is that archetypal patterns manifest themselves in images. While the pattern may be fixed, the images that give expression to that pattern come from the interaction of the archetype with its social setting. For example the underdeveloped part of the psyche is what Jung termed the ‘shadow'. We are both attracted to and afraid of this part of ourselves, especially when it is not well understood, or to use a more psychological language, integrated into consciousness. The exact form the shadow takes will vary from person to person but typically it will induce a certain attraction combined with a sense of fear or unease. The vampire and the criminal are common images of this archetype. We are unaccountably fearful or drawn to these figures. As we shall see, in House disease expresses both House's fascination with his shadow and his frustration and anxiety when it eludes his conscious grasp – something that he is at different times more and less relaxed about.

Jung goes still further in suggesting that it is the interplay of archetypes and society which gives rise to the fundamental ideas on which cultures are founded. There is a sense in which again this can be thought of as the interplay between pattern and image, only this time the interaction is occurring in society as a whole rather than in the life of a particular individual.

The unconscious … is the source of the instinctual forces of the psyche and of the forms or categories that regulate them, namely the archetypes. All the most powerful ideas in history go back to archetypes. This is particularly true of religious ideas, but the central concepts of science, philosophy, and ethics are no exception to this rule. In their present form they are variants of archetypal ideas, created by consciously applying and adapting these ideas to reality. For it is the function of consciousness not only to recognise and assimilate the external world through the gateway of the sense, but to translate into visible reality the world within us.

(Jung 1931: para. 342)

It is easy to develop this point to realise that there is an archetypal component to our conception of what constitutes ‘health'. This is to see illness in psychosomatic terms. Jungian authors such as Maguire (2004) and Ramos (2004) have in their different ways explored this territory. Their approach is to see illness as a disruption of the body's healthy and balanced system of self-regulation. It follows that one way of conceptualising disease is that it is an image of disruption to the archetypal substrata of the psyche. While Ramos explores how the body may symbolise and express such disruption, Maguire concentrates on the archetypal dimension of skin, as the semi-permeable barrier between the inner self and the outer world that is breached by illness. It is also to conceptualise health in holistic terms which sees humans as body and psyche immersed in a social environment. (Lipowski 1984). This is also how House thinks. As he succinctly puts it, ‘Your mind controls your body. If it thinks you're sick it makes you sick.’ (Airborne, 3: 18).

This consideration of what constitutes health takes us to another understanding of how ‘health’ is considered. What ‘health’ is varies from person to person and changes over time. In Jungian terms, the archetypal view of health is that it is a state of being in which the body's energy is balanced and flowing freely. Jung calls this type of energy ‘libido’ and it is both activated and channelled via the archetypes. Importantly, to have a mind and body that are in balance with each other does not require adaptation to the social setting – indeed the social setting may be contributing to the imbalance in the first place. Again this corresponds to Gregory House's view of matters and is what underlies his constant berating of the management of Princeton-Plainsboro Teaching Hospital. House's work is largely mental, he works on solving why patients react in the way they do. His request to the management is not ever for more resources (House uses those available to him with abandon and as he sees fit) but rather for less interference to enable him to deduce why a given disease is taking the particular course it is. The problem with his actions is that they often involve complicated and sometimes life-threatening interventions.

The disease detective

This raises the question: why is House driven to such ends? Part of the answer to this lies in the association that the screenwriters have created between House and the filmic and literary genres of detective fiction. While House is a physician and a medical diagnostician, the way he approaches his job, and indeed the way that he opts to live his life, is more like that of his legal counterpart, the detective. Throughout the series the parallels between House and Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes are made clear and deliberate. (They are explored thoroughly elsewhere in this volume by Susan Rowland in her chapter House Not Ho(l)mes.) For our purposes it is enough to note the similarity in their names: House and Holmes. Both House and Holmes have close male colleagues: Holmes has Dr J Watson as his fidus Achates (faithful friend) and House has Dr J Wilson. Both House and Holmes are musical: Holmes played the violin and House's instruments of choice include the electric guitar, piano and harmonica. While Holmes used cocaine recreationally, House takes large amounts of Vicodin to relieve the pain of an infarction in his leg muscles (which also provides the narrative justification for House's cane). Finally, House lives at 221B (Hunting, 2: 07) and Holmes famously lived at the fictional address of 221B Ba...