1

Introduction

On 12 March 2010, the Times Education Supplement (TES) in London screamed: ‘Fraught heads spend half-term in data hell’. It is one of many recent articles in the media reflecting the growing view of many in the profession that teaching and school management in England have become overloaded with impenetrable data from such a wide variety of sources that practitioners cannot keep track of what is available, never mind use it to effect the change for which it was produced. At system level, education in England is characterised by an almost manic obsession with tinkering (and acronyms), which over the last couple of decades has reached operatic proportions, and data measures have not been immune. Many government policies, driven (critics would say) by the hubris of politicians who lack the conceptual apparatus to discern the difference, have confused improvement with change and left many in the teaching profession foundering in the wake of ever-increasing complexity: data is collected centrally but at a significant time-cost locally to schools; it is analysed prescriptively by third parties who are perceived to lack empathy with teachers; it is interpreted by a priesthood of expertise that alienates practitioners; and it is generally underutilised in classrooms by those charged with improving educational outcomes. Accountability has likewise been abandoned to the fetish of the market as authorities sidestep the norms of robustness1 to elevate performance to a level that defies analysis by befuddled professionals. It is not a situation unique to education, of course – health service provision has similarly suffered – but it reflects the desire of successive governments to put data into the hands of stakeholders across a wide range of public services to inform choice about quality and access.

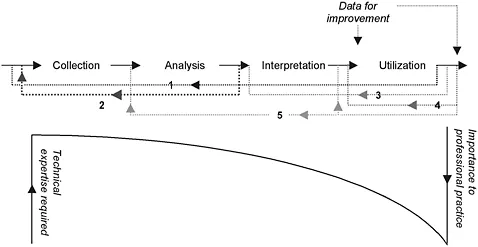

Yet despite these shortcomings – or perhaps because of them – the UK is now a major player – if not the major player – globally in terms of school and student data. Its collection and analysis, not to mention the opportunities it provides to academics to carry out good-quality school effectiveness research, has become the template of choice for policy-makers from countries as far afield as Australia (Downes and Vindurampulle 2007) and Poland (Jakubowski 2008). Over the past decade, various measures for gauging pupil attainment and progress in schools have been introduced: from simple threshold measures of raw academic attainment (such as the percentage of pupils obtaining a particular set of examination grades) to the latest complex contextual value-added (or ‘intake adjusted’) models that take account of a wide range of factors outside the control of schools. These developments have, by and large, been greeted favourably by teachers, and rightly so, though they have sometimes been made to serve two masters simultaneously: to inform school improvement through target setting and to facilitate the government’s accountability agenda through the publication of performance data. However, there are obstacles to extending the use of data even within a profession that welcomes it, one of which is the fact that the terminology used carries with it a context-specific lexicon whose terms and cognates, while straightforward to those familiar with their provenance, have different shades of meaning in everyday life. To a modest extent, this book seeks to prise open that ‘black box’ and explain the concepts, terminology and processes behind the collection, analysis, interpretation and utilisation of data in schools: from measures of attainment and progress, to non-cognitive metrics for social and emotional aspects of learning and staff responsibility. It is an ambition best served (we think) by considering in depth the English system, which leads the field, rather than describing in lesser detail many systems from different countries, though of course all data systems share some common features. For one thing, there is an obvious ‘flow’ to data processes, from collection through analysis and interpretation to utilisation (see Figure 1.1), and it is a simple matter to represent in each system the typical learning feedback cycles within that flow: systemic practice learning (1) when the experience of utilisation is fed back to those who decide what data to collect; systemic technical learning (2) when the experience of analysis is fed

back; professional learning (3) when the experience of utilisation informs new interpretative approaches; personal learning (4) when utilisation leads to better utilisation; and institutional learning (5) when the experience of utilisation leads schools to new ways of analysing the data passed to them by outside agencies. Additionally, most systems share the fact that the collection and analysis of data both require high levels of technical expertise, and engagement with the interpretation and utilisation of data (where it can most effectively be used for improvement) requires higher levels of professional expertise (see Figure 1.1).

The introduction of complex data systems in England, as elsewhere, is the culmination of years of sustained public argument about how best to measure pupil performance in a way that takes context into account, and sheds light on progress as well as on standards. This book explores the limitations of current arrangements in light of these arguments, and explores the potential of various measures to guide student and teacher self-evaluation, to set targets for pupils, teachers, schools and local authorities,2 to target resources, to hold schools publicly responsible for underperformance, to evaluate the efficacy of remedial initiatives, to identify good practice, to assess and reward responsibility, and to inform policy in relation to emerging issues like school choice, equality of opportunity and post-compulsory progression. Of course, all school data systems suffer from the disadvantage of being processed mechanistically by the algorithms of the chosen model, so they cannot operate obliquely to answer the all-important question of how best to educate young people and deploy staff so that no one is disadvantaged, nor can they use differently prioritised metrics to capture the diverse ambiguity of school life. They can cope directly and technologically with one aspect at a time, but it requires the human touch to put them all together and interpret the results as a way of guiding practice. So we have included chapters on developing metrics for social and emotional learning and assessing staff responsibility, to take account (respectively) of how pupils feel about their own learning and what teachers and managers think about their work and how it is rewarded.

We have written Using Effectiveness Data for School Improvement with a wide readership in mind:

• School practitioners: not just those with responsibility for interpreting and using school effectiveness data as part of their leadership roles within schools – head teachers, school data managers, heads of department and the like – but more widely among classroom practitioners, to reflect the growing importance of data in official professional standards. For them, we hope the book will facilitate a more critical engagement with data at every level of practice.

• Those working for local government, and commercial and third-sector organisations offering services to schools as school improvement partners and professional development providers. For them, we hope the book will provide material to stimulate more informed, effective and innovative uses of data, and make a significant contribution to the crucial process of self-evaluation in schools.

• Those individuals and groups who are motivated to contribute to new systemic initiatives like Charter Schools, Academies, ‘Free’ Schools and Voucher Schemes, and those who hold schools to account for their impact on the academic outcomes of young people: members of school governing bodies, school inspectors, and politicians at local and national level. We hope the book will provide them with food for thought about the insights that attainment data can provide and the limitations inherent in using such data to draw conclusions about the effectiveness of schools and teachers.

• Academics engaged in educational research, specifically in the fields of educational effectiveness, school improvement and school leadership.

There are many ways in which the contents of a book like this can be organised. We have settled on a chronological sequence and the chapters are sectioned in three parts: ‘The past: why data is used’, in which we consider the research and policy background from which effectiveness measures emerged; ‘The present: how data is interpreted’, in which we explore the technical aspects of the two most widely used models for school effectiveness data in England; and ‘The future: why data is important’, in which we use the principles of school effectiveness measures and a range of school improvement techniques to illustrate the way new metrics can be developed, employed and managed.

In the ‘Past’ section, Chapter 2 discusses, in research terms, the historical journey from raw-threshold to refined-contextual measures of school effectiveness, and Chapter 3 is a review of research and policy on pupil attainment and value-added data. In the ‘Present’ section, Chapter 4 describes and examines UK government models, Chapter 5 deals similarly with Fischer Family Trust models, Chapter 6 debates issues relating to differential effectiveness and the interpretation of data, and Chapter 7 explores how best to blend data from different sources. The final ‘Future’ section suggests some new metrics in Chapter 10 for dealing with social and emotional aspects of learning and in Chapter 11 for assessing staff responsibility for data-related tasks, and discusses ways of managing data for school improvement (Chapter 8) and understanding professional attitudes to it (Chapter 9). The book finishes (Chapter 12) by challenging the complexity of some current measures and the extent to which they are fit for purpose.

While the chronological framework is our way of structuring the book’s wide-ranging content, for some readers who are already familiar with the technical aspects of effectiveness measures, the ‘Future’ section will be a place to engage with stimuli to current practice and organisation. For those readers wanting to deepen their technical understanding around the issues and contradictions of effectiveness data, the ‘Present’ section will provide the insights they are seeking. For most, the ‘historical’ first section, charting as it does the development of the tools described in the middle and final parts, will serve as a guide through the maze of literature in the field. Overall, we hope the book makes a contribution to school improvement; specifically, to the role that effectiveness data can play in informing classroom practice and management. We feel that teachers need the confidence to look beyond the superficial acceptance of data as analysed and interpreted by others. It is the essence of being a professional to be conscious of this need, even when it is accompanied by a fear of the consequences. Myth, no matter how beguiling, is the most treacherous of all sources of evidence – it becomes the thing it pretends to be – but it cannot sustain professional practice in any meaningful way for any length of time, so teachers and school leaders must be able to look real evidence steadfastly in the eye and if necessary abandon that which was previously secure. The analysis and interpretation of data is the mechanism by which the truth about performance of (and in) schools is acquired, as long as the technical mechanisms and shortcomings are understood to the extent that they can challenge the unproven certainties of convention. While local context shapes the perception of effectiveness, the demand for it is universal. We suggest that the knowledgeable utilisation of data in schools can go some way to meeting that demand.

Footnotes