1 Lilliputians or leviathans?

NGOs as advocates

Barbara Rugendyke

The Global Call to Action against Poverty can take its place as a public movement alongside the movement to abolish slavery and the international solidarity against apartheid. . . . Like slavery and apartheid, poverty is manmade and it can be overcome and eradicated by the actions of human beings.

(Nelson Mandela, 3 February 2005, at the launch of the

Make Poverty History campaign in Trafalgar Square, London)

What did my 15-year-old daughter have in common with Prime Minister Tony Blair, Nicole Kidman, Kate Moss, the rapper P. Diddy and Nelson Mandela in 2005? They all wore white ‘Make Poverty History’ wristbands, as did all of her schoolmates at the secondary school she attended in Oxford in that year. The wristbands were so ‘cool’ that peer pressure to have one was intense. Being publicly seen to be a supporter of a non-government organisation (NGO) or of a campaign supported by NGOs has become trendy in parts of the Western world, whether you are a prime minister, model, rock star or school student, or one of the world’s greatest human rights activists. While wearing a bit of plastic may seem to be tokenism, the advocacy work of non-government organisations has become an increasingly important global phenomenon. So important is it that former US president Bill Clinton recently ranked the influence of NGOs, along with the extension of democracy and the internet, as one of the three global changes since the demise of the Cold World which give ordinary people the capacity to effect change in the world:

There will always be problems in the world. . . . But because of the rise of non-government organisations in a world that is more democratic, in a world where the internet gives people more access to information, we don’t have the excuse that we can’t do anything about the problems we care about because the people we voted for in the last election didn’t win.

(Clinton 2006: 13)

Representing local, regional and national constituencies in Western nations, NGOs historically acted primarily at the local scale in ‘developing’ or Southern nations as they sought to improve the quality of life of people in disadvantaged communities. However, in little more than a decade, there has been a major shift in NGO practice; where once NGOs concentrated their work on establishing projects to do things like build water supplies or encourage income generation, the same NGOs have increasingly devoted resources to advocacy campaigns directed at global actors such as the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, the World Trade Organization and multinational corporations. In so doing, and facilitated by advances in communications technologies, NGOs have themselves globalised, forming new strategic alliances in order to maximise their impact.

Simultaneously, the growing cooperation of NGOs in global advocacy campaigns has resulted in such groundbreaking and highly successful campaigns as Jubilee 2000, which mobilised 24 million people internationally under the slogan ‘Drop the Debt’. When 24 million people from over 60 countries sign a petition, politicians take notice (Mayo 2005: 174). After people lobbied the G7 meeting in 1998, world leaders at the Cologne G8 summit in 1999 agreed to cancel $100 billion of debts owed by the poorest nations (Bedell 2005). The continuing Make Poverty History campaign is a UK-based national movement which is part of a worldwide movement – the Global Call to Action against Poverty (GCAP) – which not only targets those wielding political and financial might, but also strengthens NGOs to build broad-based public support for their causes. In 2005, the Make Poverty History campaign had 540 member organisations in the United Kingdom alone committed to it, including charities, development NGOs, trade unions and faith communities. Only six months after its launch, 87 per cent of the United Kingdom’s population was aware of the campaign and 8 million people in the UK wore its white wristband (makepovertyhistory 2006). The Global Call to Action against Poverty coalition involves organisations in over 100 countries around the world and claims to have mobilised 53.5 million people to take action in support of its aims to tackle global poverty by lobbying for trade justice, more and better aid and further debt cancellation (GCAP 2006).

The effects of the Make Poverty History campaign were abundantly obvious in the United Kingdom during 2005. The Make Trade Fair component resulted in supermarkets vying to sell fair trade products, county councils producing brochures to tell the public where they could obtain fair trade produce, churches advertising themselves as ‘fair trade’ churches and displaying ‘Make Poverty History’ banners, and fair trade fashion parades and fair trade markets being held. In April 2005, 250,000 people took part in an overnight vigil for trade justice in Westminster. In Fair Trade Week, the public were barraged with publicity about the importance of trade justice, from human ‘bananas’ parading the streets, to street stalls and a concerted media campaign. Some muesli packets described where every ingredient was sourced, who had produced it, and how the purchase of the pack had directly assisted producers in Africa. Consumers could not only feel it doing them good, but feel they were doing the world good by eating the product! Sainsbury’s supermarket chain in Britain reported a 70 per cent increase in fair trade sales over a 12-month period, fair trade turnover has been growing by 20 per cent a year in Europe since 2000, and sales are projected to grow by 50 per cent per annum in Australia (Phillips 2006). Fair trade seems to be catching on, perhaps because responding to this focus of NGO advocacy gives ordinary people a sense of ‘belonging’, or of responsibility and direct involvement – their consumption, they hope, will result in direct benefits to poor producers.

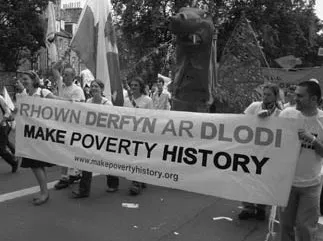

Figure 1.1 Welsh campaigners on the Make Poverty History march, 2 July 2005, Edinburgh

That poverty in Africa was a major UK general election issue in 2005, to which the media gave much air time and column space, resulted from persistent pressure from the NGOs. That it was on the agenda at the Gleneagles G8 meeting was also largely a result of concerted lobbying by the NGO community, assisted by the associated Live 8 concert at Gleneagles (Gosch 2005): a ‘bizarre confluence of politics and populism within the UK’ (Geldof 2005: xxviii). An estimated 250,000 people took to the street in Edinburgh to demand world leaders take action to make poverty history (makepovertyhistory 2006). Although reactions by NGOs to the G8’s decisions related to debt relief were mixed – ‘the people have roared but the G8 has whispered’ – that debt relief was so firmly on the agenda at all is widely attributed to the Make Poverty History campaign (Button 2005; Elliott 2005; Hodkinson 2005: 15). Thus NGO attempts to influence public opinion in order to influence national and global leaders to undertake policy changes are clearly having an impact and seem to be realising Clark’s early speculation about the growing concentration by NGOs on advocacy: ‘If it were possible to assess the value to the poor of all such reforms they might be worth more than all the financial contributions made by NGOs’ (1991: 150).

Much has been written about the increasing emphasis placed on advocacy by NGOs and the ways in which communications technologies have enabled NGOs or other activist organisations to build new strategic alliances to assist them to advocate for change (Wiseberg 2001; Leipold 2002; Clark 2003; McCaughey and Ayers 2003; Meikle 2003; Rolfe 2005). Media reports about the effectiveness or otherwise of global campaigns abound (Button 2005; Hodkinson 2005; Nason and Lewis 2005). However, few detailed studies have been undertaken as a basis for gauging the extent to which NGOs ‘going global’ with their advocacy work has contributed to poverty alleviation: ‘since advocacy . . . is relatively new and has evolved into a very dynamic process, there is not a lot of empirical data available on the extent of advocacy within NGOs’ (Lindenberg and Bryant 2001: 205). Some authors have recently called for research to ‘improve our understanding of NGOs as both subjects of development research and as actors in development processes, since these are inextricably linked’ (Lewis and Opoku-Mensah 2006: 674). Some writings about NGOs have been justly criticised because ‘More often than not they [NGOs] escape scrutiny and are simply posited as alternative signs of hope against dominant development discourse’ or because comparative studies designed to reach a wide readership ‘can only scratch the surface of each of the cases’ (Hilhorst 2003: 2–3). To date, there is little empirical research to use as a basis for answering the question: just how effective is NGO advocacy in achieving changes which contribute to improved quality of life for poor communities in the world’s poorer nations? Hence this volume. While it cannot address that larger question in its entirety, it brings together empirical work about the extension and the impacts of the advocacy efforts of development NGOs, which is largely previously unpublished and which ‘better reflects empirical realities of the world of NGOs’ (Lewis and Opoku-Mensah 2006: 673). This book presents evidence for the growing effectiveness of NGOs in harnessing greater public support for their goal of achieving greater equity, and in influencing the policies and practices of global institutions. It also describes the complexities of the resulting relationships. In doing so, it explains a vitally important global trend for in this NGO activity, according to the NGOs (and to world leaders like Nelson Mandela and Bill Clinton), lies the potential for civil society to impact on the global and national institutions and associated structures and systems which perpetuate poverty by determining access to resources and power.

Within this volume, the NGOs referred to are those which are not for profit, are usually based within ‘Northern’ nations and are not self-serving. Although many now receive some funding from government sources, their management is independent of government and those which are the focus of this book, as their primary mandate, seek ‘to relieve suffering and promote development in poor areas, especially Southern countries’ (Sogge 1996a: 3). Such NGOs not only transfer materials and resources to the South, but they also transfer information and, increasingly, engage in lobbying and campaigning work in pursuit of their broad objectives of poverty alleviation.

NGOs’ influence enlarged

NGOs have increased in popularity as a means of seeking to improve quality of life for those for whom poverty and disadvantage are a daily reality. Their diversity, the formation of new organisations, and the demise or change in name or focus of others, along with their dispersed nature, make it extremely difficult to collect accurate data about their numbers and size. However, many commentators have recorded growing numbers of NGOs across the globe. During the 1980s, the number of NGOs registered in OECD countries increased from 1,700 in 1981 to 4,000 in 1988 (Porter 1990). Northern NGO spending increased from US$2.8 billion in 1980 to US$5.7 billion by 1993 (Edwards and Hulme 1995). Moreover, in 2001, the grants distributed by international and Northern NGOs from OECD member countries were estimated to be US$10.4 billion (OECD 2002). By 2000, at least 35,000 NGOs were believed to be working internationally (Edwards 2002). As they have grown in number, they have grown in size. Lewis and Opoku-Mensah (2006) reported that a Newsweek article in September 2005, based on data from a Johns Hopkins University study, emphasised that NGOs have become ‘big business’ and, by 2002 and across 37 nations, their total estimated operating expenditure was US$1.6 trillion.

Active NGOs have also proliferated throughout the developing world, with a large number of new organisations formed to work in service delivery and, increasingly, to engage in campaigning. In 1990, over 10,000 NGOs were registered as development organisations in Bangladesh alone (Williams 1990). An increase of 60 per cent in numbers of indigenous NGOs was reported in Botswana between 1985 and 1999 and there was a 115 per cent increase in local NGOs in Kenya between 1978 and 1987 (Fowler 1991). Similarly, the number of registered NGOs in Nepal increased from 220 in 1990 to 1,210 in 1993 and in Tunisia from 1,886 in 1988 to 5,186 in 1991 (Edwards 2004: 21). It has even been suggested that India has at least 2 million active NGOs (Wikipedia 2006a). It goes almost without saying that, with increasing numbers of NGOs operating throughout the globe and increased funds being distributed by them, NGOs have been increasingly influential. But why have NGOs increased so in popularity and influence?

NGOs have a number of claimed advantages: they are able to be more flexible and innovative and respond to need more quickly than bilateral and multilateral donors; they can implement and administer projects and programmes at lower cost than other aid delivery bodies; they are more likely to work with and through local institutions; they are more likely to emphasise processes of change and skills learnt rather than provision of quantifiable tangible goods (the preference of official donors); and they are more likely to take risks associated with working in geographically remote areas, sectors neglected by governments, or politically unpopular areas (Tendler 1982; Rugendyke 1994). Perhaps most important among the ‘articles of faith’ which rapidly became accepted about NGOs is that they claim to have better links with the neediest groups in poor communities and regions of the world. Not constrained by having to work through governments, they are able to work directly with the poor using participatory, ‘bottom-up’ processes of project identification and implementation, based on longer experience of working with local people and more accurate knowledge and understanding of local needs and capabilities. Critically, given the focus of this book, their independence from government allows them to engage in lobbying and campaigning in pursuit of greater global equity and social justice.

Shifting paradigms in development theory have also accorded NGOs new status. These changes have been detailed extensively elsewhere (Rugendyke 1994; Anderson 2003; Ollif 2003), so will only be given cursory attention here. Disenchantment with growth and modernisation theories of development which predominated during the 1960s and 1970s and with the later dominant radical development theories which contributed to new understandings that development, as both condition and process, was perpetuated by inequitable global structures meant that by the mid-1980s theorists were referring to an ‘impasse’ in development theory (Booth 1985; Sklair 1988; Corbridge 1990). During the 1980s, a strand of thought which had existed parallel to the large-scale deterministic theories and emphasised the ability of people to bring about change, through what was later called ‘human agency’, became increasingly influential (Giddens 1982; Watts 1988; Long 1992). Alongside abstract development theory, which largely described macro-level structural change, debate about the most appropriate forms of development practice did not subside. During the 1980s, commentary about development practice increasingly prioritised the involvement of local communities at every stage of development planning. With broad appeal across the political spectrum, and variously called ‘empowerment’, ‘participatory development’, ‘democratisation’ or ‘populism’, this emphasis recognised that social movements may be the fundamental agents of social change and opened the way for greater interest in non-state actors, including NGOs, in the development process (Corbridge 1992; Slater 1992). Much has since been written about the role of civil society in promoting positive change at every scale – from communities to nations and the global scene – and history has since demonstrated the enormous potential of ‘people power’ to effect change (Clark 2003; Keane 2003). This new focus on civil society, on the role of non-state actors in bringing about change, gave new legitimacy to the participatory approach of NGOs (Edwards and Gaventa 2001; Edwards 2004; Potter et al. 2004). More recently, their ascendancy and new popularity with governments and official aid agencies have also been seen to be directly related to their relevance to a larger neoliberal economic and political agenda (Pearce 2000; Craig and Porter 2006; Robbins 2006).

The persistence of this alternative view of development and the new status it accorded NGOs, along with recognition of their benefits and disillusionment with larger aid agencies, given the failures of many large-scale development projects, meant that from the 1980s NGOs were increasingly supported financially by both bilateral and multilateral donors. With growing numbers and income, NGOs became increasingly influential. However, that influence was accompanied by greater scrutiny of their activities, which questioned their impacts, legitimacy and transparency, and by stronger demands for accountability (Clark 1991; Edwards and Hulme 1992, 1995; Smillie and Helmich 1993; Smillie 1995; Sogge 1996a).

Recognising their increased importance globally, NGOs have engaged in an ongoing struggle to find the best ways to work towards global equity. Staff of development NGOs continue to grapple with the dilemmas and uncertainties of development ‘on the ground’ in disadvantaged communities. While that has often been seen to be both their focus and their strength, they have been criticised equally for having a range of weaknesses, one of which is that, historically, they have had little impact at a global level, with accusations made in the early 1990s that they had failed to address the wider-scale structural causes of poverty (Bebbington and Farrington 1992; Edwards and Hulme 1992). In the following decade, NGOs sought to remedy this by increasing their commitment to advocacy, convinced this was the way to maximise both the impacts and the cost-effectiveness of their work (Edwards 2002).

The term ‘advocacy’ is generally used by NGOs to refer to campaigning, which involves attempts to change public opinion, and lobbying, which aims to change ‘structures, policies and practices which institutionalise poverty and related injustice’ (Anderson 2003: 35). Campaigning encourages public support for lobbying activities, so, in essence, both attempt to influence policy formation as a means of facilitating positive change in people’s lives. While there is a diversity of approaches to advocacy, it is ‘self-evidently of a political nature (both in itself and in terms of what it seeks to achieve)’ (Eade 2002: x).

Expanding horizons: globalising NGO advocacy

Reasons for the growth in advocacy activity have been well documented (Edwards and Hulme 2000; Pearce 2000; Chapman and Fisher 2002; Edwards 2002), but it primarily arose from ‘the realisation that development and humanitarian relief projects will never, in and of themselves, bring about lasting changes in the structures which create and perpetuate poverty and injustice’ (Eade 2002: ix). Thus, the increased commitment...