![]()

Part I

Origins

![]()

1. Before the long sixteenth century

1.1

Market cooperation and the evolution of the pre-Hispanic Mesoamerican world-system

Richard E. Blanton and Lane F. Fargher

The emergence of the early modern European world-system, according to Wallerstein (1974), represented a sea change in human socioeconomic organization inasmuch as there was a vast increase in the interregional exchange of staple goods, unlike world-empires and mini-systems that principally featured the long-distance exchange of preciosities. The latter, Wallerstein argued, were only elite symbols of conspicuous consumption and hence lacked the system-shaping potential of staple goods that account “more of men’s economic thrusts than luxuries” (ibid.: 42). This argument has been criticized (e.g., in Abu Lughod 1989; Blanton and Feinman 1984; Schneider 1977), and here we elaborate these critiques by developing a goods-centered approach to expand on Wallerstein’s structural opposition of preciosities and staples, before showing how the approach can be applied in the case of pre-Hispanic Mesoamerica. We trace the long-term history of Mesoamerican goods systems, then identify what we consider to be the central driving force in the emergence of the Mesoamerican world-system, namely, a changing consumer propensity to consume exotic and costly goods that we identify as bulk luxury goods. Lastly, we contextualize bulk luxury consumption in relation to a growing core-zone market economy.

Outline of a theory of goods

Research on the role of goods in culture and social life found in sources including Appadurai (1986), Douglas and Isherwood (1979), Gregory (1982), McCracken (1988), Mintz (1985), Sahlins (1994), and Schneider (1987) informed our application of a goods perspective to world-systems analysis (Blanton et al 2005, with our colleague Verenice Heredia Espinoza). In our formulation, both preciosities and staples are viewed as potentially system-shaping and will figure into any explanation of cultural, social, demographic, technological, and agroecological change, including world-system change. However, how, and the degree to which, any particular good is implicated in change varies across space and time. To characterize this variation, we identify three broad categories of goods: Prestige Goods, Regional Goods, and Bulk Luxury Goods.

Prestige goods

Prestige goods are similar to those identified by Wallerstein as preciosities in that they serve, in part, as symbols of elite status. However, anthropologists have come to better understand how such goods figure into processes of social change, principally in relation to the emergence of a governing elite in many chiefdoms and pre-modern states (Brumfiel and Earle 1987; Hayden 1995; Peregrine 1992). Exclusive goods manufactured from rare materials and using technologically sophisticated methods are an ideal medium for calculated gifting aimed at political faction-building and for purposes of competitive feasting between members of an elite (Blanton et al 1996). However, typically, they have little role in the economic activities of the great majority of people and play only a limited direct role in world-system evolution.

Regional goods

Regional goods facilitate the transition to increased production and the attendant revisions in work scheduling and foodways as commoner households respond to both growing tax obligations and growing commercial opportunities (e.g., Blanton and Fargher 2010; Blanton et al 1999: Ch. 4; Fargher 2009). In general, regional goods were produced and exchanged at the geographical scale of regional tribute flows and periodic markets rather than the world-system scale.

Bulk luxury goods

A bulk luxury goods category (the phrase is from Kepecs 2003: 130) is a necessary amendment to Wallerstein’s concept of a preciosity as they occupy a middle ground between the rare and exclusive prestige goods and the regional goods that were available to many consumers (Blanton et al 2005: 274). Although costly and often exotic, they are consumed by commoner as well as elite households, for example in rites of household social reproduction such as feasts, weddings and funerals (e.g., Mintz 1985). There are profound system-shaping consequences when commoner households in an emerging core region increase bulk luxury consumption. Supplier regions undergo periphery incorporation as substantial numbers of households respond to external demand, potentially bringing change in agroecology, demography, labor mobilization, production methods, work intensification and regional market systems (Blanton et al 2005). We argue that bulk luxuries are a key causal factor promoting the development and integration of the core-periphery structures of world-systems, whether in early modern Europe or elsewhere.

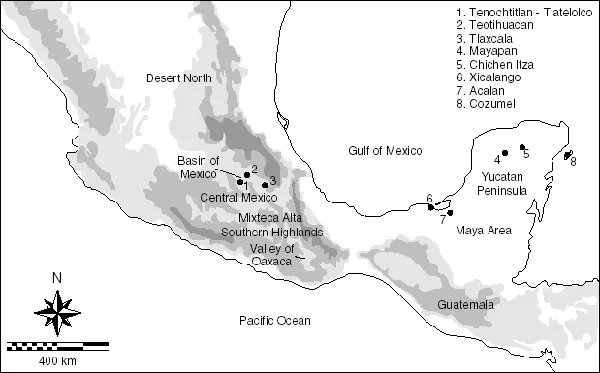

The world of goods and world-system evolution in pre-Hispanic Mesoamerica

We contextualize the emergence of a Mesoamerican world-system by outlining the ways in which goods have featured in sociocultural change over a span of approximately 3,000 years. Mesoamerican long-distance exchange of prestige goods such as jade, stingray spines, marine shell and magnetite mirrors intensified during the Early and Middle Formative Periods (1400–500 BCE), but these goods were produced and consumed only in small quantities, principally by high status households (e.g., Marcus and Flannery 1996: Chapters 8 and 9). The Late Formative through Classic Periods (500 BCE–CE 950) marked the emergence of states, cities, market systems and regional goods, as indicated by the intensification and standardization of utilitarian pottery (e.g., Blanton et al 1999: Ch. 4; Feinman et al 1984). For example, during this time in the Valley of Oaxaca, Mexico (Figure 1.1.1), we detect the emergence of a regional division of labor including intensification of food production in some localities. In other areas, there was an increased production of handicrafts such as pottery, palm frond products, salt, chert tools and fiber (Fargher 2004; Feinman and Nicholas 2010). World-system growth is first evident after about CE 300 with the advent of bulk luxuries such as “Thin Orange” pottery, which was used widely at Teotihuacan and elsewhere (Kolb 1986). At this time we first detect a process of periphery incorporation, for example in tropical regions, where cotton production was increased to satisfy growing consumer demand in arid and high-elevation cities such as Teotihuacan, where cotton cannot be cultivated (e.g., Stark et al 1998).

Figure 1.1.1 Places mentioned in the text

During the Postclassic Period (CE 950–1521), important bulk luxury goods that moved between regions at the scale of Mesoamerica and were consumed across social sectors included polychrome pottery, green obsidian blades, cacao (chocolate), fine sea salt and cotton (Blanton et al 2005). From a world-systems perspective, these are analogs of the wool, cotton, sugar, spices and tea that featured in the growth of the early modern European world-system (cf. Mintz 1985; Sahlins 1994; Wallerstein 1974).

The growing consumption of these bulk luxury goods was powerfully system-shaping, bringing unprecedented levels of economic growth as well as social, demographic, agroecological and technological change. For example, obsidian mining became more sophisticated, involving shaft and tunnel techniques surpassing earlier shallow pit mining (Charlton and Spence 1982: 24; Cobean 2002) and specialist producers developed more efficient methods for blade tool production (e.g., Clark 1985) that made obsidian (especially green obsidian) a commodity more widely available across the length and breadth of Mesoamerica. Cotton production also underwent a technological revolution during the Postclassic as it became a highly sought after and widely consumed commodity, especially in Central Mexico (Anawalt 2001; Berdan 1987; Hicks 1994). Growing cotton consumption also spurred the development of new markets for secondary industries, especially cochineal, a brilliant and fast red dye produced in regions including Tlaxcala, the Mixteca Alta and the Valley of Oaxaca (e.g., Donkin 1977). The production of low-grade salt for use as a dye-fixing mordant was another important secondary industry in the Basin of Mexico (Parsons 2001: 248). The Postclassic saw a major expansion in the production and consumption of sea salt, especially in the Maya lowlands (Kepecs 1999: 315, 516, 2003), which required new forms of labor mobilization, including seasonal labor migration to work coastal saltpans in marginal locations (Kepecs 1999: 422). In Guatemala, late pre-Hispanic cacao production probably exceeded six million pounds per year (Bergmann 1969: 94) from large monocrop plantations or estates that had been carved out of tropical forest (Bergmann 1969, Millon 1955: 130–33). Cacao production involved major changes in agroecology, production scheduling (as cacao production would displace local subsistence production) and labor mobilization.

Discussion

Wallerstein (1974: Ch. 2) saw the decline of the feudal mode of production of medieval European and the corresponding rise of the capitalist yeoman farmer as an important social transition underlying a new European, and, eventually, world-wide division of labor. Here we address the analogous social and cultural foundations of the emerging Mesoamerican world-system, but we take a direction unlike Wallerstein’s mode of production analysis by focusing on the evolution of marketplace institutions in the emerging Central Mexican core zone. As Central Mexico emerged as Mesoamerica’s preeminent core zone, its trade and political interactions with other Mesoamerican regions intensified, especially involving the flow of commodities exchanged with tropical lowland regions. Expansion of core zone influence stimulated the growth of secondary foci of economic activity in semiperipheral polities linking the highlands to tropical regions, for example, in trade emporia in the Xicalango and Acalan regions. Increased macroregional integration altered regional networks of cities across a wide zone from Central Mexico to the Maya area, including the growth of new commercial and political centers in Yucatán at Chichen Itzá and Mayapán (Kepecs 2007; Smith and Berdan 2003) and trade emporia such as Cozumel (Sabloff and Rathje 1975).

The Central Mexican region emerged as Mesoamerica’s major Postclassic core zone, especially in the Basin of Mexico where a Late Postclassic population that exceeded one million persons was integrated politically by the Aztec Triple Alliance empire (Berdan et al 1996) and economically through a complex division of labor and market system (Berdan 1985; Blanton 1996; Hassig 1985; Hodge and Smith 1994; Nichols et al 2002; Smith 2010; Smith and Berdan 2003). Commercial growth in Central Mexico extended to commoners who attended distant markets outside their own polity and ethnic boundaries (e.g., Durán 1967: Vol. 1, 177) and who had a wide range of goods choices extending to bulk luxury goods. The region’s, and Mesoamerica’s, most important marketplace at Tlatelolco was a vast walled concourse that served up to an estimated 50,000 people on major market days (Cortés 1986: 103).

We attribute the relative elaboration of the Central Mexican commercial system to social and cultural changes that allowed for an expansion of market cooperation across polities and across social sectors. We think this was a key ingredient in world-system growth because, in pre-Hispanic Mesoamerica, as in all complex societies, market cooperation presents problems, often restricting commoner commercial participation to only local market venues where participants are socially familiar with commercial transaction partners (Blanton forthcoming). The lack of trust that market transactions can take place honestly will be a disincentive to market participation, but other disincentives to participation abound, for example when marketers must travel through dangerous foreign territory to reach distant markets and when market transactions are between persons of different ethnicities or polities. Additionally, commoners will not likely participate in markets managed by biased local officials whose adjudicative decisions may favor persons of their own ethnicity, political group, or social standing. Geographically and socially broadly based market participation is based on trust that markets will be safe, that most market participants will observe an ethic of fairness, and that there will be adjudicative certainty so that when market disputes occur they will be resolved in a neutral and fair manner.

Uniquely in Mesoamerica, in Central Mexico market cooperation problems were resolved through the development and wide acceptance of novel institutional and cultural changes accompanying the rise of the Postclassic polities. In one of these changes, three of the major antagonists of the militarily conflictive Middle Postclassic Period (the Mexica, Acolhua, and Tepaneca) agreed to form a political alliance to consolidate imperial power in Central Mexico and beyond (Berdan et al 1996), thus enhancing possibilities for safe interregional travel. Of equal importance is the fact that during the Postclassic Period, most market management, including marketplace adjudication of disputes, came to be vested in an organized group of commoner merchants called the Pochteca. The Pochteca was a vast Central Mexican organization that operated as a semiautonomous paragovernmental system within the larger authority structure of the Aztec empire (van Zantwijk 1985: Ch. 7). Although the Pochteca were commoners operating largely outside the official structure of the state, they maintained a high-level autonomous judicial authority within marketplace venues (Offner 1983: 156), were known for their judicial neutrality in commercial matters (Sahagún 1950–69, Book 8: 69; cf. van Zantwijk 1985: Ch. 7), and upheld an ethical code that emphasized fairness in matters of trade (van Zantwijk 1985: 171). The most important commercial venue in all of Mesoamerica by the end of the pre-Hispanic sequence was the massive market concourse at Tlatelolco, which was designated as a distinct social domain in which the judicial authority of the Aztec state was suspended, leaving market management entirely in the hands of the Pochteca (Sahagun 1950–69, Book 9: 24). No comparable institutional arrangement for market management was present in other Mesoamerican regions (Blanton forthcoming).

In addition to safer travel provided by imperial integration and effective market management, institutional and cultural changes during the Central Mexican Postclassic Period weakened notions of ethnic identity while serving to minimize the divide between nobility and commoners to a degree that was unusual in Mesoamerica. The cultural foundations of these two important social outcomes, we suggest, are to be found in the promulgation of a slightly variant but largely uniform mythic history shared among the Postclassic Nahua (Central Mexican) peoples (Fargher et al 2010). According to mythic history, the different ethnic groups making up the Nahua peoples could trace their origins to “primitive” Chichimecs from northern arid regions who migrated into Central Mexico from a shared origination point (Boone 1991). While different migrating groups eventually colonized distinct regions of Central Mexico to establish polities and adopt “civilization” (“neo-Toltec” Nahua culture and language), a mythic scheme emphasizing a shared originating point and shared ethnic origins resulted in a weak and contingent sense of ethnicity that largely dissolved ethnic boundaries in Central Mexico, producing what Stark (2008: 44) refers to as an “ethnic mosaic” (cf. Brumfiel 1994; van Zantwijk 1985). We think this would have facilitated market participation beyond local systems.

Mythic history documented how “primitive” desert peoples were t...