eBook - ePub

The Science of Writing

Theories, Methods, Individual Differences and Applications

- 448 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Science of Writing

Theories, Methods, Individual Differences and Applications

About this book

Conceived as the successor to Gregg and Steinberg's Cognitive Processes in Writing, this book takes a multidisciplinary approach to writing research. The authors describe their current thinking and data in such a way that readers in psychology, English, education, and linguistics will find it readable and stimulating. It should serve as a resource book of theory, tools and techniques, and applications that should stimulate and guide the field for the next decade.

The chapters showcase approaches taken by active researchers in eight countries. Some of these researchers have published widely in their native language but little of their work has appeared in English-language publications.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Science of Writing by C. Michael Levy, Sarah Ransdell, C. Michael Levy,Sarah Ransdell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Communication Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

— 1 —

A NEW FRAMEWORK FOR UNDERSTANDING COGNITION AND AFFECT IN WRITING

John R. Hayes

Carnegie Mellon University

Carnegie Mellon University

Alan Newell (1990) described science as a process of approximation. One theory will replace another if it is seen as providing a better description of currently available data (pp. 13-14). Nearly 15 years have passed since the Hayes-Flower model of the writing process first appeared in 1980. Since that time a great many studies relevant to writing have been carried out and there has been considerable discussion about what a model of writing should include. My purpose here is to present a new framework for the study of writing — a framework that can provide a better description of current empirical findings than the 1980 model, and one that can, I hope, be useful for interpreting a wider range of writing activities than was encompassed in the 1980 model.

This writing framework is not intended to describe all major aspects of writing in detail. Rather, it is like a building that is being designed and constructed at the same time. Some parts have begun to take definite shape and are beginning to be usable. Other parts are actively being designed and still others have barely been sketched. The relations among the parts — the flow of traffic, the centers of activity — although essential to the successful functioning of the whole building, are not yet clearly envisioned. In the same way, the new framework includes parts that are fairly well developed — a model of revision that has already been successfully applied, as well as clearly structured models of planning and of text production. At the same time, other parts (such as the social and physical environments), though recognized as essential, are described only through incomplete and unorganized lists of observations and phenomena — the materials from which specific models may eventually be constructed.

My objective in presenting this framework is to provide a structure that can be useful for suggesting lines of research and for relating writing phenomena one to another. The framework is intended to be added to and modified as more is learned.

The 1980 model

The original Hayes-Flower (1980) writing model owes a great deal to cognitive psychology and, in particular, to Herbert Simon. Simon’s influence was quite direct. At the time Flower and I began our work on composition, I had been collaborating with Simon on a series of protocol studies exploring the processes by which people come to understand written problem texts. This research produced cognitive process models of two aspects of written text comprehension. The first, called UNDERSTAND, described the processes by which people build representations when reading a text (Hayes & Simon, 1974; Simon & Hayes, 1976), and the second, called ATTEND, characterized the processes by which people decide what is most important in the text (Hayes, Waterman, & Robinson, 1977). It was natural to extend the use of the protocol analysis technique and cognitive process models to written composition.

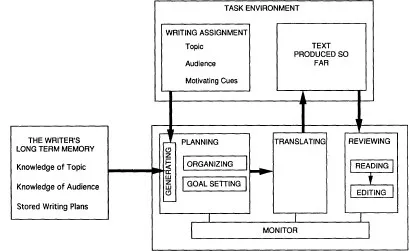

Figure 1.1. The Hayes-Flower model proposed in 1980.

Figure 1.1 shows the Hayes-Flower model as it was originally proposed (Hayes & Flower, 1980). Figure 1.2 is a redrawing of the original model for purposes of graphic clarity. It is intended to better depict the intended relations in the original rather than as a substantive modification. In the redrawing, memory has been moved to indicate that it interacts with all three cognitive writing processes (planning, translating, and revision) and not just with planning — as some readers were led to believe. The names of the writing processes have been changed to those in more current use. Certain graphic conventions have been clarified. The boxes have been resized to avoid any unintended implication of differences in the relative importance of the processes. Arrows indicate the transfer of information. The process-subprocess relation has been indicated by including subprocesses within superprocesses. In the 1980 model, this convention for designating subprocesses was not consistently followed. In particular, in the original version, the monitor appeared as a box parallel in status to the three writing process boxes. Its relation to each process box was symbolized by undirected lines connecting it to the process boxes. As is apparent in the 1980 paper (pp. 19-20), the monitor was viewed as a process controlling the subprocesses: planning, sentence generation, and revising. Thus, in Figure 1.2, the monitor is shown as containing the writing subprocesses.

Figure 1.2. The Hayes-Flower model (1980) redrawn for clarification.

The model, as Figure 1.1 and 1.2 indicate, had three major components. First is the task environment; it includes all those factors influencing the writing task that lie outside of the writer’s skin. We saw the task environment as including both social factors, such as a teacher’s writing assignment, as well as physical ones such as the text the writer had produced so far. The second component consisted of the cognitive processes involved in writing. These included planning (deciding what to say and how to say it), translating (called text generation in Figure 1.2, turning plans into written text), and revision (improving existing text). The third component was the writer’s long-term memory, which included knowledge of topic, audience, and genre.

General organization of the new model

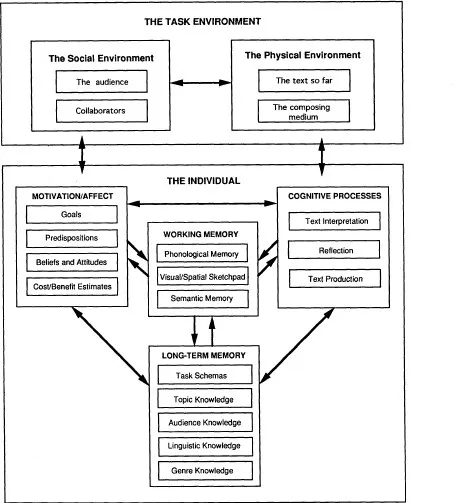

Figure 1.3 shows the general organization of the new model. This model has two major components: the task environment and the individual. The task environment consists of a social component, which includes the audience, the social environment, and other texts that the writer may read while writing, and a physical component, which includes the text that the writer has produced so far and a writing medium such as a word processor. The individual incorporates motivation and affect, cognitive processes, working memory, and long-term memory.

Figure 1.3. The general organization of the new model.

In the new model, I group cognition, affect, and memory together as aspects of the individual; I depict the social and physical environments together as constituting the task environment. Thus, rather than a social-cognitive model, the new model could be described as an individual-environmental model.

In what follows, I will say more about modeling the individual aspects of writing than about the social ones. This is because I am a psychologist and not a sociologist or a cultural historian. It does not mean that I believe any of these areas is unimportant. Rather, I believe that each of the components is absolutely essential for the full understanding of writing. Indeed, writing depends on an appropriate combination of cognitive, affective, social, and physical conditions if it is to happen at all. Writing is a communicative act that requires a social context and a medium. It is a generative activity requiring motivation, and it is an intellectual activity requiring cognitive processes and memory. No theory can be complete that does not include all of these components.

There are four major differences between the old model and the new: First, and most important, is the emphasis on the central role of working memory in writing. Second, the model includes visual-spatial as well as linguistic representations. Scientific journals, schoolbooks, magazines, newspapers, ads, and instruction manuals often include graphs, tables, or pictures that are essential for understanding the message of the text. If we want to understand many of the texts that we encounter every day, it is essential to understand their visual and spatial features. Third, a significant place is reserved for motivation and affect in the framework. As I will show, there is ample evidence that motivation and affect play central roles in writing processes. Finally, the cognitive process section of the model has undergone a major reorganization. Revision has been replaced by text interpretation; planning has been subsumed under the more general category, reflection; translation has been subsumed under a more general text production process.

The task environment

The social environment

Writing is primarily a social activity. We write mostly to communicate with other humans. But the act of writing is not social just because of its communicative purpose. It is also social because it is a social artifact and is carried out in a social setting. What we write, how we write, and who we write to is shaped by social convention and by our history of social interaction. Our schools and our friends require us to write. We write differently to a familiar audience than to an audience of strangers. The genres in which we write were invented by other writers and the phrases we write often reflect phrases earlier writers have written. Thus, our culture provides the words, images, and forms from which we fashion text. Cultural differences matter. Some social classes write more than others (Heath, 1983). Japanese write very different business letters than Americans. Further, immediate social surroundings matter. Nelson (1988) found that college students’ writing efforts often have to compete with the demands of other courses and with the hurly burly of student life. Freedman (1987) found that efforts to get students to critique each others’ writing failed because they violated students’ social norms about criticizing each other in the presence of a teacher.

Although the cultural and social factors that influence writing are pervasive, the research devoted to their study is still young. Many studies are, as they should be, exploratory in character and many make use of case study or ethnographic methods. Some areas, because of their practical importance, are especially active. For example, considerable attention is now being devoted to collaborative writing both in school and in the workplace. In school settings, collaborative writing is of primary interest as a method for teaching writing skills. In a particularly well-designed study, O’Donnell, Dansereau, Rocklin, Lambiote, Hythecker, and Larson (1985) showed that collaborative writing experience can lead to improvement in subsequent individual writing performances. In workplace settings, collaboration is of interest because many texts must be produced by work groups. The collaborative processes in these groups deserve special attention because, as Hutchins (1995) showed for navigation, the output of group action depends on both the properties of the group and those of the individuals in the group. Schriver (in press) made similar observations in extensive case studies of collaboration in document design groups working both in school and industry.

Other research areas that are particularly active are socialization of writing in academic disciplines (Greene, 1991; Haas, 1987; Velez, 1994), classroom ethnography (Freedman, 1987; Sperling, 1991), sociology of scientific writing (Bazerman, 1988; Blakeslee, 1992; Myers, 1985), and workplace literacy (Hull, 1993).

Research on the social environment is essential for a complete understanding of writing. I hope that the current enthusiasm for investigating social factors in writing will lead to a strong empirical research tradition parallel to those in speech communication and social psychology. It would be regrettable if antiempirical sentiments expressed in some quarters had the effect of curtailing progress in this area.

The physical environment

In the 1980 model, we noted that a very important part of the task environment is the text the writer has produced so far. During the composition of any but the shortest passages, writers will reread what they have written apparently to help shape what they write next. Thus, writing modifies its own task environment. However, writing is not the only task that reshapes its task environment. Other creative tasks that produce an integrated product cumulatively such as graphic design, computer programming, and painting have this property as well.

Since 1980, increasing attention has been devoted to the writing medium as an important part of the task environment. In large part, this is the result of computer-based innovations in communication such as word processing, e-mail, the World Wide Web, and so on. Studies comparing writing using pen and paper to writing using a word processor have revealed effects of the medium on writing processes such as planning and editing. For example, Gould and Grischowsky (1984) found that writers were less effective at editing when that activity was carried out using a word processor rather than hard copy. Haas and Hayes (1986) found searching for information on-line was strongly influenced by screen size. Haas (1987) found that undergraduate writers planned less before writing when they used a word processor rather than pen and paper.

Variations in the composing medium often lead to changes in the ease of accessing some of the processes that support writing. For example, on the one hand, when we are writing with a word processor, including crude sketches in the text or drawing arrows from one part of the text to another is more difficult than it would be if we were writing with pencil and paper. On the other hand, word processors make it much easier to move blocks of text from one place to another, or experiment with fonts and check spelling. The point is not that one medium is better than another, although perhaps such a case could be made, but rather that writing processes are influenced, and sometimes strongly influenced, by the writing medium itself.

As already noted, when writers are composing with pen and paper, they frequently review the first part of the sentence they are composing before writing the rest of the sentence (Kaufer, Hayes, & Flower, 1986). However, when writers are composing with a dictating machine, the process of reviewing the current sentence is much less frequent (Schilperoord, in press). It is plausible to believe that the difference in frequency is due to the difference in the difficulty of reviewing a sentence in the two media. When writing with pen and paper, reviewing involves little more than an eye movement. When composing with a dictating machine, however, reviewing requires stopping the machine, rewinding it to find the beginning of the sentence, and then replaying the appropriate part.

The writing medium can influence more than cognitive processes. Studies of e-mail communication have revealed interesting social consequences of the media used. For example, Sproull and Kiesler (1986) suggested that marked lapses in politeness occurring in some e-mail messages (called flaming) may be attributed to the relative anonymity the medium provides the communicator.

Such studies remind us that we can gain a broader perspective on writing processes by exploring other writing media and other ways of creating messages (such as dictation, sign language, and telegraphy) that do not directly involve making marks on paper. By observing differences in process due to variations in the media, we can better understand writing processes in general.

The individual

In this section I discuss the components of the model that I have represented as aspects of the individual writer: working memory, motivation and affect, cognitive processes, and long-term memory. I will attend to both visual and verbal modes of communication.

Working memory

The 1980 model devoted relatively little attention to working memory. The present model assumes that all of the processes have access to working memory and carry out all nonautomated activities in working memory. The central location of working memory in Figure 1.3 is intended to symbolize its central importance in the activity of writing. To describe working memory in writing, I draw heavily on Baddeley’s (1986) general model of working memory. In Baddeley’s model, working memory is a limited resource that is drawn on both for storing information and for carrying out cognitive processes. Structurally, working memory consists of a central executive together with two specialized memories: a “phonological loop” and a visual-spatial “sketchpad.” The phonological loop stores phonologically coded information and the sketchpad stores visually or spatially coded information. Baddeley and Lewis (1981) likened the phonological loop to an inner voice that continually repeats the information to be retained (e.g., telephone numbers or the digits in a memory span test). The central executive serves such cognitive tasks as mental arithmetic, logical reasoning, and semantic verification. In Baddeley’s (1986) model, the central executive also performs a number of control functions in addition to its storage and processing functions. These functions include retrieving information from long-term memory and managing tasks not fully automated or that require problem solving or decision making. In the writing model, I represent planning and decision making as part of the reflection process rather than as part of working memory. Further, I specifically in...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- Theories of Writing and Frameworks for Writing Research

- Analytic Tools and Techniques

- Individual Differences and Applications

- References

- Author index

- Subject index