1

Introduction

CHRISTOPHER J. HOPWOOD , MARK A. BLAIS , and MATTHEW R. BAITY

The Personality Assessment Inventory (PAI; Morey, 1991) is a 344-item multiscale self-report measure of constructs relevant for a wide range of psychological assessment applications. The PAI differs from other wellknown self-report multiscale inventories in several important ways that are largely a consequence of the construct validation approach to test construction (Cronbach & Meehl, 1955; Jackson, 1970; Loevinger, 1957) that guided PAI development. This approach combines theoretical and empirical procedures for selecting the constructs to be measured and items reflective of those constructs. One illustrative effect of this underlying philosophy is that PAI scales are clearly labeled with contemporary terms for constructs that are commonly used among practitioners regardless of their theoretical orientation. Other features of the PAI were designed to ease the administrative burden of the test, given the practical obstacles to lengthy assessment practices (Piotrowski & Belter, 1998). For instance, the PAI requires a lower reading level than similar inventories (Schinka & Borum, 1993) and benefits from relative brevity even though all of its scales have non-overlapping items.

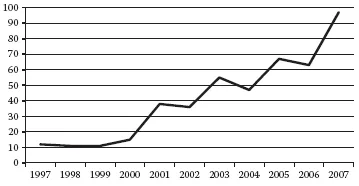

Together these practical features of the test, along with the focus in the construct validation method of test construction on measuring constructs with substantial theoretical articulation and empirical support, resulted in an instrument that is adaptable across a range of psychological assessment applications. For example, interpretive software has been developed for clinical (Morey, 2000), personnel selection (Roberts, Thompson, & Johnson, 2000), and forensic (Edens & Ruiz, 2005) applications. The broad relevance of the instrument likely accounts, in part, for the rising use of the PAI in applied settings (Belter & Piotrowski, 2001; Piotrowski, 2000; Lally, 2003; Stredny, Archer, Buffington-Vollum, & Handel, 2006). The PAI is also increasingly used by psychological researchers. Figure 1.1 shows the number of peer-reviewed journal references for the PAI in a PsycInfo search* from 1997 to 2007. The steadily increasing slope characterizing these data clearly illustrates the accelerated adoption of the PAI for psychological assessment research.

Peer-Reviewed PAI Publications: 1997–2007

Figure 1.1 Growing popularity of the PAI.

Although PAI research has been conducted in a wide range of psychological assessment contexts (see Morey, 2007) and detailed guides for using the PAI in mental health treatment settings have been published (e.g., Morey, 1996; Morey & Hopwood, 2007), systematic reviews and clinical suggestions regarding the use of the PAI for diverse practice applications have been limited. This book is intended to be a resource for practicing assessment psychologists or other professionals and graduate students in a range of settings where the PAI may be used. Chapters have been written by experts who regularly conduct psychological assessments using the PAI across a range of contexts and populations. This chapter will briefly introduce the development, structure, and interpretation of the PAI. More thorough reviews of these issues have been provided elsewhere (e.g., Morey, 1991; 1996; 2003; 2007; Morey & Hopwood, 2007; 2008).

DEVELOPMENT

The construct validation approach recognizes the importance of both adequate theoretical descriptions of constructs that an instrument is intended to measure and empirical methods to refine the items and scales that measure them. Construct validation assumes that focusing narrowly on maximizing any single psychometric characteristic of a test will likely negatively impact other characteristics (Morey, 2003). For example, scales that are designed to differentiate clinical from nonclinical populations may do so adequately, but they may also be more limited in describing individuals from clinical populations who vary in their level of severity.

PAI development began with a consideration of the range of constructs that might be regarded as important for treatment planning and behavioral predictions by psychological assessors. Criteria for this search included the stability of use in the clinical psychology lexicon, extent of use in contemporary practice, breadth of validity evidence, and quality of theoretical articulation (Morey, 1991). This process ultimately resulted in four domains comprising 22 full and 31 subscales, as shown in Table 1.1.

The first of these domains involves the measurement of response style. Validity scales were developed to signify random, negative, and positive responding that may affect the interpretation of other scales. Clinical scales measure constructs similar to those in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM; APA, 1994), although there are a number of divergences, in part because some current DSM constructs are quite new to the clinical literature and have limited validity evidence, but also because of theoretical differences in the DSM and PAI approaches to measurement (Morey, 1991). Treatment consideration scales were designed to supplement clinical scales in predicting client behavior. These include measures of aggression, suicidal ideation, environmental stress and support, and treatment motivation. Finally, interpersonal scales assess client personality characteristics that can affect the expression of clinical disorders and are important for developmental hypotheses and treatment planning (Pincus, Lukowitsky, & Wright, in press).

Content Validity

A major focus in developing the PAI, and one of the features that sets the PAI apart from similar instruments, involves content validity. Content validity refers to the degree to which item content is relevant to and representative of the targeted construct (Haynes, Richard, & Kubany, 1995). Adequate content validity requires attention to both the breadth and depth of measured constructs. Breadth involves the coverage of diverse aspects of broad phenomena. To ensure adequate breadth, subscales were created for nine clinical scales and one treatment consideration scale (Table 1.1). For example, the Depression scale has subscales measuring depressive affect (e.g., dysphoria), depressive cognitions (e.g., hopelessness), and physiological symptoms of depression (e.g., difficulty sleeping). The composition of these subscales was based on theoretical and empirical descriptions of the structure of psychological syndromes measured by the PAI. Subscales are particularly important because substantial symptomatic heterogeneity can occur even among individuals with the same psychiatric diagnosis. Subscales may also be helpful in considering the effects of treatments. For example, in some instances, subscales correspond to symptoms that are differentially targeted in particular therapies, such as DEP-C with cognitive therapy or DEP-A with psychopharmacology (Morey, 1996). As such, patients may be matched to treatments based on subscale profiles, and different subscales can be used to indicate changes attributable to particular interventions. In some instances, subscale elevations may relate to phenomena that are somewhat independent of their parent scale. For example, the MAN-G scale can often indicate self-esteem independent of a manic episode or bipolar disorder (Morey, 1996).

TABLE 1.1 PAI Scales and Subscales

Depth refers to the extent to which a scale adequately measures the varying severity levels of a clinical construct. As noted previously, a scale in which all items maximally differentiate people who have or do not have a particular diagnosis is limited in assessing severity among people with the same diagnosis. However, such a differentiation can be critical in certain assessment contexts. For example, people with moderately severe depressive episodes may have a low risk for harming themselves and may be able to function adequately, even if somewhat ineffectively, with the help of outpatient treatment. In contrast, people with markedly severe depression may be at high risk to harm themselves and may require inpatient stabilization.

Three features enhance the construct depth of the PAI scales. The first is the four-point, rather than true-false, item response scale. Likert scaling increases the amount of true score variance captured per item and allows respondents to indicate the severity of each element (i.e., item) of the measured construct. This facilitates acceptable scale reliability with fewer items. Second, large community and clinical samples were gathered for normative data. Comparison of an individual’s clinical scale score to the community sample mean and variability can be useful in determining the likelihood of being a member of a diagnostic group; understanding the score in the context of the clinical normative sample is useful for determining severity relative to others in a clinical setting. Third, the use of Item Response Theory to select items that were maximally endorsed at varying levels of construct severity further enhanced the depth of construct coverage. For example, an item that reads “Sometimes I feel sad” might differentiate very happy from somewhat depressed people, whereas an item that reads “I wish my life were over” would likely differentiate depressed from severely depressed people. Each PAI scale includes items that were selected for their ability to indicate varying severity levels of measured constructs.

Discriminant Validity

Discriminant validity, or the degree to which scores on a test do not correlate with scores from other tests that are not designed to assess the same construct (Campbell & Fiske, 1959), is closely linked to content validity. Although various psychopathology and personality constructs tend to systematically relate to one another, measures of those constructs should not correlate more strongly than those variables co-occur in nature. Such measures should also not strongly relate to non-clinical characteristics, such as demography. The more faithful test item content is to the construct of interest, the less likely those items are to unintentionally measure something else.

Several procedures enhanced the discriminant validity of PAI scales. A bias panel that included representatives from several ethnic and cultural backgrounds was asked to identify items they thought might inadvertently indicate a cultural characteristic; identified items were removed from the initial pool. Next, psychopathology and personality assessment experts were asked to sort items onto what they felt were the appropriate scales and incorrectly sorted items were removed. Perhaps most importantly, all scales were constructed with non-overlapping items, because tests with items that load onto more than one scale have inflated scale intercorrelations and obfuscated scale meanings. Finally, Differential Item Functioning methods were used after initial data were collected to further ensure discriminant validity. This method assesses the relation of items to the construct they were intended to measure as well as to other characteristics such as demography, and was used to select items with acceptable convergent (i.e., strong correlations of PAI items with their intended scales) and discriminant (i.e., weak correlations between PAI items and other scales or demographic characteristics) validity.

Relatedly, the PAI is not normed separately for men and women. Gender-specific norms have the potential to complicate interpretation by yielding prevalence rates that are similar across genders, even when the prevalence of the corresponding behaviors differs. A clinical example highlights the importance of this difference. Suppose a woman’s gender-specific T-score is 65 on the Alcohol Problems scale, and that her raw score might correspond to 55T relative to men, who, on average, tend to be more likely to exhibit alcohol problems. She could be considered more likely than a man with a gender-specific T-score of 60 to have a drinking problem, even though her score, and thus presumed likelihood, is actually lower than his. In fact, only two PAI scales demonstrate clinically significant mean differences across genders: Antisocial Features and Alcohol Problems both have higher mean scores in men than in women (Morey, 1991), although neither of them show differences as dramatic in magnitude as the above example. Importantly, these differences correspond to epidemiological research showing that men are more likely to be diagnosed with antisocial personality disorder and alcohol use disorders than are women (Sutker & Allain, 2001).

PAI Indicators

Several extra-scale indicators (Table 1.2) were developed after the publication of the PAI that are helpful in making important predictions about behaviors such as dissimulation, suicide, violence, and treatment participation. The approaches guiding the development of these indicators varied, with some being purely empirical (e.g., Rogers and Cashel Discriminant Functions) and others combining theoretical and empirical developmental strategies (e.g., Malingering, Defensiveness, and Predictive Indicators). The resulting indicators also vary in the kinds of behaviors they are optimized to predict, and can be classified broadly into those related to test validity and those related to dysfunctional behavior.

TABLE 1.2 PAI Indicators

These indicators can often be used in conjunction with PAI scales to augment predictive accuracy. For instance, the Rogers and Cashel Discriminant Functions have been shown to be sensitive to dissimulation, even though they also have the important property of being mostly unrelated to indicators of psychopathology. As such, they may reflect “pure” measures of test faking that is uninfluenced by the respondent’s actual clinical problems. This is very helpful, since most validity scales, including PAI, PIM, and NIM, have substantial correlations with clinical scales, complicating the dissociation of response styles and clinical problems (Morey, 1996). Predictive indicators can also be used in conjunction with clinical scales. For example, whereas the suicidal ideation (SUI) scale asks about the extent to which the respondent is consciously considering ending their life, the Suicide Potential Index (SPI) taps other personality features that are associated with carrying out the act. Research shows that these indicators are both associated with suicidal behavior (e.g., Hopwood, Baker, & Morey, 2008), suggesting their conjunctive use improves the assessment of overall suicide risk level.

Construct Validity

The final step in developing the PAI, assessing the construct validity of scales and indicators, will continue for the life of the instrument. Initial examination of these issues involved correlating PAI scales with previously validated measures and comparing PAI scale scores across individuals from various diagnostic groups. The second edition of the PAI manual (Morey, 2007) describes these initial validation studies as well as research conducted following the development of the test. Some of this research will be highlighted in chapters in this book to the extent that it relates to specific applications of the PAI.

INTERPRETATION

PAI data are typically interpreted in light of one or more referral questions offered by the examinee or a referring party and in the context of other information from interactions with the respondent, interviews with referring parties or collateral informants, record review, and other psychological methods. A model for the integration of PAI data with findings from other assessment instruments is outlined in Chapter 12 of this volume.

Interpretation of psychological assessment data is a complex activity that, among other considerations, is informed by the context of and reason for the evaluation. PAI software reports may be helpful, depending upon this context. Many of the chapters of this book focus on interpretive issues with the PAI in particular settings. This section focuses more narrowly on the psychometric meaning of PAI data, independent of the assessment context. Also, because other resources describe the PAI interpretation process in detail (Morey, 1996, 2003; Morey & Hopwood, 2007), the current section briefly highlights important and distinct aspects of PAI interpretation regarding the examinee’s approach to testing, psychiatric diagnosis, and behavioral predictions, rather than providing a step-by-step interpretive guide.

Response Style

An adequate assessment of the respondent’s approach to test materials is critical in psychological evaluations, and its importance can escalate in many settings. For instance, forensic assessment can sometimes be adversarial or create secondary motivations for respondents to either downplay or emphasize certain characteristics (e.g., see Chapters 5, 7, 10, and 11 of this volume). The PAI includes multiple methods to assess response style that can be organized according to the type of response issue they are designed to detect. PAI scales and indicators were designed to indicate random (e.g., INF, ICN), positive (e.g., PIM, DEF, CDF), and negative (e.g., NIM, MAL, RDF) responding. More specific indicators were des...