CHAPTER 1

Introduction

Trevor C. Salmon

International relations, or international politics, is not merely a field of study at university but is an integral aspect of our (increasingly international) everyday lives. We now live in a world where it is impossible to isolate our experiences and transactions from an international dimension. If a British student watches the sitcom Friends or the soap opera Neighbours they are both learning about and participating in a culture different from their own. If a student flies from Washington DC to London they are subject to international air space agreements and contributing to global warming. If a student chooses to buy a fair-trade coffee they are making a conscious decision about contributing to a state and a people’s development. Should you work for an international company or international organization, or even if you work for a locally based company there will inevitably be an international dimension to the functioning of the company as it negotiates the myriad of EU laws, international trade laws, international employment laws and tax laws. The limits to how international relations will continue to impact your life is tremendous.

Studying international relations or politics enables students and professionals to better comprehend the information we receive daily from newspapers, television and radio. People not only live in villages and towns, but form part of the wider networks that constitute regions, nations and states. As members of this world community, people have to be equally aware of both their rights and their responsibilities—and should be capable of engaging in important debates concerning the major issues facing the modern international community. One crucial feature of the world in which we live is its interconnectedness—geographically, intellectually and socially—and thus we need to understand it.

BOX 1.1 INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS

- Individuals live in villages/towns but are also part of a wider community

- Individuals have rights as well as responsibilities

- The world is interconnected

Originally, the study of international relations (a term first used by Jeremy Bentham in 1798) or politics was seen largely as a branch of the study of law, philosophy or history. However, following the carnage of the First World War there emerged an academic undertaking to understand how the fear of war was now equal only to the fear of defeat that had preceded the First World War. Subsequently, the first university chair of international relations was founded at the University of Wales in 1919. Given such diverse origins, there is no one accepted way of defining or understanding international relations, and throughout the world many have established individual ways of understanding international relations. Any attempt to define a field of study is bound to be somewhat arbitrary and this is particularly true when one comes to international relations or politics.

The terms ‘international relations’ and ‘international politics’ are often used interchangeably in books, journals, websites and newspapers. In the last generation some have preferred to use ‘world’ or ‘global’ politics where the focus of activity is not the state but some notion of a global community or global civilization. For many laypersons there is no real difference between these words, but technically there is more than a semantic difference as terms can reflect a difference of focus and field of study.

BOX 1.2 FOCUS AND FIELDS OF STUDY

International relations ≠ International politics ≠ World politics ≠ Global politics

Similarly, there are legal, political and social differences between domestic and international politics. Domestic law is generally obeyed, and if not, the police and courts enforce sanctions. International law rests on competing legal systems, and there is no common enforcement. Domestically a government has a monopoly on the legitimate use of force. In international politics no one has a monopoly of force, and therefore international politics has often been interpreted as the realm of self-help. It is also accepted that some states are stronger than others. Domestic and international politics also differ in their underlying sense of community—in international politics, divided peoples do not share the same loyalties—people disagree about what seems just and legitimate; order and justice. It is not necessary to suggest that people engaged in political activity never agree or that open and flagrant disagreement is necessary before an issue becomes political: what is important is that it should be recognized that conflict or disagreement lies at the heart of politics. To be political the disagreement has to be about public issues. Recent experience has taught us that the matters that were once purely domestic and of no great relevance internationally can feature very prominently on the international political agenda. Outbreaks of bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and avian flu all exemplify how domestic incidents can become international and can lead to foreign policy changes and commitments.

BOX 1.3 THE DOMESTIC AND THE INTERNATIONAL

Domestic

- Laws generally agreed and obeyed

- Sanctions

- Monopoly of force

- A sense of community

International

- Competing legal systems

- No common enforcement

- No monopoly of force (each state judge and jury in own case)

- Diverse communities

Today, international relations could be used to describe a range of interactions between people, groups, firms, associations, parties, nations or states or between these and (non)governmental international organizations. These interactions usually take place between entities that exist in different parts of the world—in different territories, nations or states. To the layperson interactions such as going on holiday abroad, sending international mail, or buying or selling goods abroad may seem personal and private, and of no particular international concern. Other interactions such as choosing an Olympics host or awarding a film Oscar are very public, but may appear to be lacking any significant international political agenda. However, any such activities could have direct or indirect implications for political relations between groups, states or international organizations. More obviously, events such as international conflict, international conferences on global warming and international crime play a fundamental part in the study of international relations. If our lives can be so profoundly influenced by such events, and the responses of states and people are so essential to international affairs, then it is incumbent on us to increase our understanding of such events. As John Donne said in 1624:

No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main. If a clod be washed away by the sea, Europe is the less, as well as if promontory were, as well as if a manor of thy friend’s or of thine own were. Any man’s death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind; and therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.

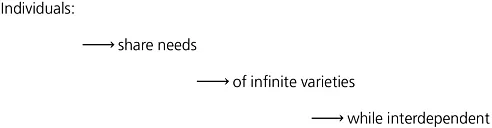

As of 2007, the world population has reached six and half billion, and it is estimated to rise to seven billion by 2013. The largest population in the world is in China with 1,321,852,000 persons, followed by India with a population of 1,129,866,000, and third is the USA with 301,139,000. The European Union has 490,426,000. The smallest population, the Vatican, has 1,000 persons. All of the individuals in these populations share basic human needs for air, food, drink and shelter and have hopes to ultimately realize their personal growth and fulfil their potential. It is also clear that there is an infinite variety of languages, cultures, religions, philosophies, states and governments. Although diverse, people are also inescapably interdependent.

The immediacy of our globalized world can be exemplified by the immediacy and international diversity of the terrorist attacks of 9/11. Within minutes of the horrific events unfolding, international news media was feeding images of the attacks throughout the world. Of 2,617 deaths, 20 per cent were born outside the United States, 110 of whom were from the European Union.

In terms of conflict, one could argue that the new age began when Napoleon marched into Russia in 1812 with an army of 453,000 men. Or with the American Civil War (1861–1865) where 617,528 men were killed and 500,175 men were injured out of a total of 2,356,000 combatants from the combined Federal and Confederate forces. Others would cite the 8,500,000 dead and 21,000,000 wounded from the First World War. Others might look to the Second World War, just over 20 years later, during which 15,000,000 to 20,000,000 combatants and 9,000,000 to 10,000,000 civilians were killed, and the first nuclear weapons were used against the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki during August 1945. More recently, there have been 111 armed conflicts recorded in 74 locations around the world between 1989 and 2000 – seven were interstate and nine were intrastate wars with foreign intervention. There are no official figures recording how many people have been killed in Iraq since 2003 although one British medical journal has estimated that 2.5 per cent of the Iraqi population died as a result of the war between March 2003 and July 2006 – a hotly disputed figure. Similarly there are no official records of how many Iraqis were killed when Saddam Hussein was President of Iraq between July 1979 and April 2003.

The study of contemporary international relations encompasses much more than war and conflict, but preserving life, justice and sustainability remains a key ingredient. During April 1986 the world’s worst nuclear power accident occurred at Chernobyl in the former USSR (now Ukraine). The Chernobyl accident killed more than 56 people immediately and exposed approximately 6,600,000 people to radiation, of whom as many as 9,000 have subsequently died from radiation-induced cancers. Twenty years later there are still areas of the Europe where farms face post-Chernobyl controls. Clearly the Chernobyl disaster exemplifies how global relationships and agendas remain crucial.

Participation in international relations or politics is inescapable. No individual, people, nation or state can exist in splendid isolation or be master of its own fate; but none, no matter how powerful in military, diplomatic or economic circles, even a giant superpower, can compel everyone to do its bidding. None can maintain or enhance their rate of social or economic progress or keep people alive without the contributions of foreigners or foreign states. Every people, nation or state is a minority in a world that is anarchic, that is, there is an absence of a common sovereign over them. There is politics among entities that have no ruler and in the absence of any ruler. That world is pluralistic and diverse. Each state is a minority among humankind. No matter how large or small, every state or nation in the world must take account of ‘foreigners’.

BOX 1.5 THE COMPLEXITIES OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS

International relations

- War

- Economics

- Socio-economics

- Development

- Environment

International relations, therefore, is too important to be ignored but also too complex to be understood at a glance. Individuals can be the victim or victors of events but studying international relations helps each one of us to understand events and perhaps to make a difference. This, however, requires competence as well as compassion.

Some come to study international relations because of an interest in world events, but gradually they come to recognize that to understand their own state or region, to understand particular events and issues they have to move beyond a journalistic notion of current events. There is a need to analyse current events, to examine the why, where, what and when, but also to understand the factors that led to a particular outcome and the nature of the consequences. Studying international relations provides the necessary tools to analyse events, and to gain a deeper comprehension of some of problems that policy-makers confront and to understand the reasoning behind their actions.

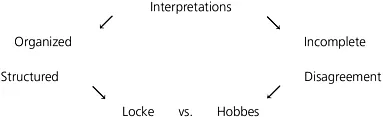

Scholars and practitioners in international relations use concepts and theories to make their study more manageable. This book will introduce both, but that is only the first step. For instance, let us consider the United Nations which currently has 192 member states. If each member state consulted with every other member state regarding a particular issue, the scale of the political transactions and exhanges would be very difficult to define as a mere number. Rather, such transactions only become intelligable when they become organized and structured to fit with a specific arrangement or interpretation of facts. However, the very act of interpreting, organizing and structuring concepts suggests that they are inaccurate and incomplete. This is one example of how social scientists frequently find themselves in disagreement about the soundness of ‘facts’, concepts or theories.

Such disputes have historically led to major philosophical disputes about the fundamental nature of international relations: the Hobbesian versus the Lockeian state of nature in the seventeenth century, and the Realist versus Utopian debate of the first part of the twentieth century. Hobbes, writing in 1651, interpreted the state of society to be: ‘continuall feare, and danger of violent death; And the life of man, solitary, poore, nasty, brutish, and short’. Hobbes also noted that:

Yet in all times, Kings and Persons of Soveraigne authority, because of their Independency, are in continuall jealousies, and in the state and posture of Gladiators; having their weapons pointing, and their eyes fixed on one another; that is, their Forts, Garrisons, and Guns upon the Frontiers of their Kingdoms; and continuall Spyes upon their neighbours; which is a posture of War.

This is not, of course, an accurate reflection of contemporary international relations, but the concepts articulated by Hobbes still reverberate in many modern fundamental assumptions about the nature of the system and of human beings. Locke took a more optimistic view and suggested that sociability was the strongest bond between men—men were equal, sociable and free; but they were not licentious because they were governed by the laws of nature. He was clear that nature did not arm man against man, and that some degree of society was possible even in the state preceding government per se. Three and a half centuries later the differing perceptions and assumptions concerning human nature that influenced Hobbes and Locke are still able to divide approaches to the study of the nature of international relations.

BOX 1.6 ASSUMPTIONS AND APPROACHES

Other concepts are equally discussed and debated. For instance, in the 1970s it was common to distinguish between domestic politics and international politics on the basis of territory. In the United States, a continental power, or the United Kingdom, an island(s), for the most part, one could distinguish between home affairs and international affairs—international affairs involved people beyond the water’s edge. For all states it involved people outside their own territory. What happened within a territorial boundary was the sole business of that territory’s government and it has historically been accepted to mean that no state or organization—except in certain circumstances authorized by the United Nations Security Council—is subject to the demands or rules of another state. However, even if states are independent and equal units in terms of the law, it is a very different matter to consider individual state’s capacity to exercise that independence or equality. For instance, as ‘equal’ members of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization it is absurd to think that Iceland, Luxembourg or Latvia have the same operational power as the United States, the United Kingdom or the Federal Republic of Germany.

International relations, even foreign relations, involve the study of the interactions that take place between seemingly disparate societies or entities, and the factors that affect those interactions. Whilst a...