![]()

1

Introduction

As human beings, we all spend a considerable amount of time and effort trying to understand ourselves and those around us. Think for a moment about the significant events that have happened to you in the last week. By significant, I mean those events that have taken up a noticeable amount of your conscious energy. Probably these events involved actions on the part of yourself or someone you know, and those actions impacted in some way on someone other than the actor. When you reflect on such events, it is likely that a central part of your thinking involves trying to understand and explain the protagonists’ thoughts and opinions, feelings and emotions, desires and intentions. Such thinking may be referred to as commonsense psychology because it is our everyday attempt to explain, as academic psychology does, the workings of the human mind and its relation to behavior. What is clear is that as adults we all do it much of the time, either alone or in conversation with others.

Commonsense psychology is not just about understanding why people did what they did in the past; it is also about trying to determine what those people will do in the future. Again, just as academic psychology is aimed at formulating theories of how past behavior may allow us to make predictions about future behavior, commonsense psychology is important in allowing us to predict how people will act in the future. Accurate prediction is important because it may enable us to anticipate how others will act in relation to us and in relation to each other. In turn, prediction and anticipation of others’ action will also allow us to formulate a plan to achieve our own goals. Achieving our goals often depends on others, either through cooperation or competition. Forming friendships requires an alignment of opinions, desires, and emotions. Achieving competitive goals may require action to stymie others’ intentions.

Commonsense psychology ranges from the very simple and automatic to the very complex and effortful. Figure 1.1 depicts an example of a relatively simple and automatic act of commonsense psychology—one person directing the attention of two others using a pointing gesture. Note that three characters are engaging in commonsense psychology. The man tries to manipulate the attention of the two women. He wants them to attend to something located some distance away. The women shift their attention from the man to the distant object or event. They understand that the man wants them to attend over there and therefore that there must be something of relevance there. This example illustrates that our shared commonsense psychology allows us to communicate effectively with, to manipulate, and to be manipulated by those around us. It also illustrates a basic fact of commonsense psychology: that the psychological states we all experience are referential in that they occur in reference to something else. The man’s pointing gesture and the attention shifts it produces in his listeners are directed toward something, presumably some object or event in the world.

FIG. 1.1. Pointing illustrates a simple act of commonsense psychology.

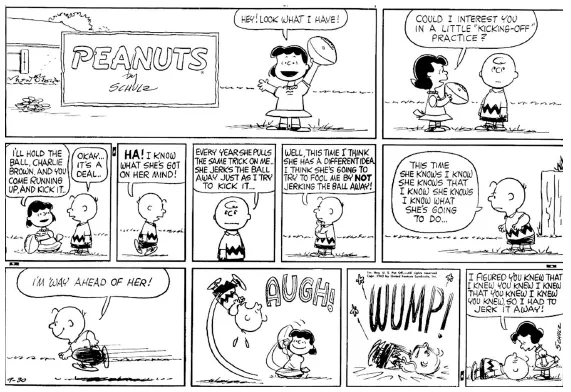

Figure 1.2 presents an example of commonsense psychology expressed through language that is rather more complex. This example shows again the role that commonsense psychology plays in predicting the future and regulating interactions. Charlie Brown is using his reasoning about Lucy’s mental states to try to predict what she is going to do and that prediction guides his own choice of action. In addition, it illustrates two more points nicely. First, the thing to which any particular psychological state refers can be another psychological state. Thus, Charlie Brown’s representation of Lucy’s thought is that Lucy’s thought is about his own thought. In this way, commonsense psychology allows for psychological states to be embedded within other psychological states. Second, commonsense psychology can occur in reference both to the psychological states of self and to the psychological states of other people. I return to these points in chapter 2. Indeed they will be a central part of this story.

FIG. 1.2. Peanuts, Copyright © United Features Syndicate, Inc.

So commonsense psychology describes our natural tendency to try to understand and predict the activities of people (and sometimes other agents such as animals). It is clearly a very salient component of mental life. Because we regularly participate in social interactions and we are embedded in overlapping sets of social networks, much of our activity impinges in some way on those around us and their activity impinges on us. Commonsense psychology is the conceptual system that we use to make sense of the social interactions and relationships that we observe and in which we participate. Just as we generally interpret the nonsocial world in terms of mechanical causes and effects, we generally interpret the social world in terms of psychological causes and effects. The causes are emotions, intentions, meanings, and other psychological categories; the effects are actions. Commonsense psychology is also a tool we use to negotiate our interactions and regulate our relationships by making predictions about future action and guiding our choice of action. In a very general way, commonsense psychology is the glue that binds us to our social worlds, allowing us to interact with others, to participate in meaningful relationships, and to function as members of a social network.

THE STUDY OF COMMONSENSE PSYCHOLOGY

The fact that this conceptual system is part of common sense does not mean it is unworthy of scientific scrutiny. It is well established that human beings throughout the world are endowed with natural forms of psychology that equip them for navigating their social worlds (Callaghan et al., 2005; Lillard, 1998). The recognition of the ubiquity of commonsense psychology in people has led in the last 20 years to the emergence of a vigorous program of scientific research in the cognitive sciences. There are various goals for this scientific enterprise. Researchers want to understand how commonsense psychology is normally involved in the organization of social action. At the same time, it is productive to consider the departures from typical social interaction seen in different forms of psychopathology as disruptions in commonsense psychology. The classic example here is autistic spectrum disorders, which have been fruitfully viewed as involving disturbances in the development of commonsense psychology (Baron-Cohen, Tager-Flusberg, & Cohen, 2000; Hobson, 1993). Recently there has even been interest in how understanding the nature of commonsense psychology may be useful in the construction of intelligently social robots (e.g., Scassellati, 2002).

Because the first step in any scientific enterprise is to describe accurately the phenomena to be explained, we start in the next chapter with a general description outlining the major features of commonsense psychology and laying the groundwork for the rest of the book. Some of these features may seem quite obvious and perhaps unworthy of comment (they are, after all, common sense). However, there is good reason to consider them closely because they provide clues to the construction of a case for how commonsense psychology is made possible. In science, it is true that insights are sometimes gained from the observation of the novel and exotic-for example, Charles Darwin’s (1839/1989) observations of creatures unique to the Galapagos Islands provided an important clue to the process of evolution by natural selection. However, insights may also be gained from taking a fresh look at phenomena that are so familiar that we barely notice them in everyday life—witness the impetus to Isaac Newton’s development of the laws of motion from the observation of an apple falling to earth. A careful consideration of certain obvious features of commonsense psychology will guide us in our explanation of its place in human psychology.

If we are to understand the place of commonsense psychology within human psychology, then we have to be able to recognize and describe it when we see it. However, here the commonsenseness of commonsense psychology may actually be an impediment because it may subtly influence our identification skills. Commonsense psychology is just as much a part of the psychological makeup of scientific psychologists as it is of everyone else. When describing the behavior of both people and many social animals, such as chimpanzees, dogs, and so forth, it is difficult not to see the expression of commonsense psychology everywhere. But, in order to describe accurately when commonsense psychology is present, we need a way of assessing commonsense psychology independently of our intuition. So how can we ensure that our scientific descriptions are not simply a reflection of our common sense? As we shall see at many points in this book, when it comes to describing the commonsense psychology of young children the situation is particularly worrisome. Adults can tell you how they understand themselves and others and to some extent we can study their commonsense psychology directly through their verbal reports. But young children, and in particular infants, are not so capable. Too often we have to infer how they think of things from observations of their actions. So, for example, when a 12-month-old infant points or follows her mother’s point, can we be sure that she understands that her mother can see something? Whether an infant is using commonsense psychology is not directly evident from the outside because we cannot observe directly the conceptual system of that infant.

So, how do we determine if and when infants and young children are using commonsense psychology? A simple answer to this question might be: “You just watch what they do and if they show behaviors that depend on commonsense psychology in an adult, then you can be fairly sure that commonsense psychology is indeed involved.” Sometimes called the argument by analogy, this strategy has a venerable history (e.g., Hume, 1739–1740/1911; Povinelli, Bering, & Giambrone, 2000; Romanes, 1883/1977; Russell, 1948;). But notice that there is a problem here. Because as adults we are inveterate commonsense psychologists, we tend to see the workings of commonsense psychology everywhere. So our tendency to ascribe commonsense psychology is not a good basis for determining whether infants actually do use commonsense psychology. It may well reflect our own natural application of commonsense psychology rather than the real properties of the infants themselves.

In the history of psychology, this problem provided an early challenge to the development of the scientific study of nonverbal creatures. When the scientific study of behavioral psychology was in its infancy in the late 19th century, the argument by analogy was explicitly used to interpret animal behavior. A beautiful example comes from Georges Romanes, an early follower of Charles Darwin, and one of the first writers to explore possible continuities in behavior between animals and human beings. Indeed he was the originator of the term comparative psychology to denote the systematic study and comparison of the behaviors of different species. In one passage, he described the behavior of a dog:

The terrier used to be very fond of catching flies upon the windowpanes, and if ridiculed when unsuccessful was evidently much annoyed. On one occasion, in order to see what he would do, I purposely laughed immoderately every time he failed. It so happened that he did so several times in succession—partly, I believe, in consequence of my laughing—and eventually he became so distressed that he positively pretended to catch the fly, going through all the appropriate actions with his lips and tongue, and afterwards rubbing the ground with his neck as if to kill the victim: he then looked up at me with a triumphant air of success. So well was the whole process simulated that I should have been quite deceived, had I not seen that the fly was still upon the window. Accordingly I drew his attention to this fact, as well as to the absence of anything upon the floor; and when he saw that his hypocrisy had been detected he slunk away under some furniture, evidently very much ashamed of himself. (Romanes, 1883/1977, cited in Mitchell, 1986, p. 444)

In this example, Romanes (1883/1977) attributed a variety of acts of commonsense psychology to the dog, of which the most complex is that implicated by the final attribution of shame. According to Romanes, the dog was ashamed because he knew that Romanes knew that he had tried to make Romanes think that he had caught the fly. This is certainly a complicated bit of psychological reasoning for a dog. Now, maybe the dog did indeed understand the complexity of the interaction between himself and his master and, as a result, experienced shame. The problem is, we cannot know for sure just from observing the dog’s behavior. It is entirely possible that rather simpler explanations are possible—perhaps the dog detected a dominance display from Romanes in the final denouement and responded as a subordinate animal in a species-typical way.

It is interesting to note that this approach to the interpretation of animal minds concerned many of Romanes’ contemporaries (e.g., Morgan, 1894; Thorndike, 1898/1965) and it was an important part of the reason that scientific psychology over the next 50 years moved in rather a wholesale manner away from attributing complex mental states (and then indeed any mental states) in the explanation of behavior of animals and humans. Whereas we have few qualms about attributing mental representations as scientific explanations of behavior these days, we would nevertheless do well to keep in mind the dangers of using our natural tendency to use commonsense psychology. Attributions of commonsense psychology to the subjects of our study may reflect our own psychology rather than that of our subjects.

In the domain of human psychology, verbal reference to concepts of commonsense psychology constitutes evidence that the speaker is using commonsense psychology. But, if we are not to rely on the argument by analogy, how do we explore the commonsense psychology of infants and very young children, who cannot show us through their language that they conceive of people’s action in psychological terms? Developmental psychology provides a more objective approach than simply relying on our own commonsense psychology. Within developmental psychology, researchers have developed a variety of scientific techniques to study what children of different ages know about people and their behavior. I examine many of these techniques in the rest of the book.

THE PLAN OF THE BOOK

We begin in chapter 2 with an outline of some of the key characteristics of commonsense psychology. This chapter also points to certain aspects of commonsense psychology that, although core features of this conceptual system, are shown to present considerable challenges to any nonverbal organism attempting to acquire and use it. These aspects of commonsense psychology are challenges in the sense that they appear not to be evident to naive learners from observing either themselves or any other organism. The challenges provide organizing themes for the explanatory account of commonsense psychology offered through the remainder of the book. In particular, I pose four challenges. The first, which I call the challenge of self-other equivalence, starts from the straightforward fact that we think of ourselves as being similar to others in the sense that we are all individuals with conscious minds. But how are we initially able to recognize this similarity between self and others when we have no direct access to others’ conscious minds and only limited experience of ourselves as objective entities? The second challenge begins with the recognition that we assume people’s psychological experiences are meaningful in the sense that they are about things in the world. We assume people see and hear things, feel emotions about things, believe things, and so on. Yet, all we ever know at the outset of other people’s psychological states is their behavior—facial expressions and actions—and we can never observe directly what other people are seeing, feeling happy or sad about, or thinking about. I call this the challenge of the object directedness of psychological states. The third and fourth challenges take off from the fact that we do acquire a commonsense psychology that recognizes self-other equivalence and object directedness. The third challenge is that of psychological diversity. If we do grasp the notion that people have similar psychological orientations to the things in the world, how do we come to the realization that different people may have different orientations to the same things, or that the same person may have different orientations to the same things at different times? Finally, how do we come to understand that despite this psychological diversity, people retain an individual identity through time? In particular, why is it that I assume that the self I know myself to be now is continuous with my self from the past and with my self in the future? This fourth challenge is that of personal identity. These questions may seem trivial at the outset (after all, they reflect basic assumptions on which commonsense psychology is founded), but we will see that they are not. It is particularly toward the provision of solutions to these challenges that the rest of the book is directed.

Once we have considered an account of what commonsense psychology is, we turn to the task of this book: elaborating an explanation of the nature of commonsense psychology and how it arises through development. In the science of psychology, there are various approaches to the understanding of its phenomena—behavior and the mental and neural bases of behavior. Experimental psychologists study how behavior varies under different conditions and thereby seek to understand how perception and cognition organize action. Neuroscientists explore the brain bases of the organization of action. Developmental psychologists use both of these approaches and others, but critically they attempt to understand psychological phenomena by examining how they change with age. The study of development is a fundamental way of understanding the nature of psychological characteristics by examining how they were built from less mature forms. The idea is that the complexity of psychological phenomena is in part explained by its transition from earlier developmental forms. Just as if we wanted to understand why Europe is partitioned into its current intricate structure of national borders, we would examine the historical record of the interactions of the peoples of that continent, so if we want to understand the form of the mind...