- 216 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

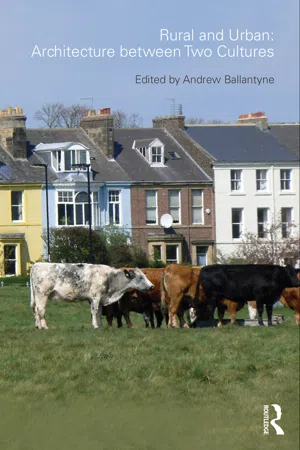

Rural and Urban: Architecture Between Two Cultures

About this book

Investigating various ways in which the cultures of the town and the countryside interact in architecture, original essays in this book written by an international range of recognized theorists will help all students of architecture and urban design understand how the urban and rural relate.

Taking a broad historical sweep, this collection draws on a symposium of the Society of Architectural Historians of Great Britain.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Rural and Urban: Architecture Between Two Cultures by Andrew Ballantyne in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Rural and urban milieux

Andrew Ballantyne and Gillian Ince

Bucolics

‘There is nothing good to be had in the country,’ said William Hazlitt, ‘or, if there is, they will not let you have it.’1 For Hazlitt the urbanite, the countryside was outside. It was outside of society—a place where everyone hated one another—and outside of civilization. ‘Their common mode of life is a system of wretchedness and self-denial, like what we read of among barbarous tribes. You live out of the world.’ Part of Hazlitt’s motivation for saying such things was the pervasive sentimentality with which the urban world has treated the countryside, since ancient times. The shepherds who sing to one another in Virgil’s Eclogues, lovelorn in an Arcadia dripping with honey and bathed in golden light, are as remote from everyday encounters with agricultural workers as the shepherds in Brokeback Mountain—a story that was originally published in the ultimate urbane environment of the New Yorker magazine, and which was then further lyricized by Hollywood actors and cinematographic glamour.2 The countryside is repeatedly presented as the place to go for true feeling. At least that is how it is presented to the urban population that eats food that comes in packets and tins, has no songs to sing, and that thinks there is a problem when it is hit by the smell of cow manure. These days the ‘urban population’ is most of us, and the countryside is less clearly separate than it was in Hazlitt’s day. There are still different worlds, which have different value systems and patterns of behaviour, but they can overlap and erupt unexpectedly. One’s study, in a house in a small village, may be filled with books and ideas that have passed through cities, and a broadband connection might often make the actual location seem insignificant, so long as one can connect to the world outside. But—to take a personal example—in Asquins, where this book was edited, there is a door, only a short walk away, that has half-a-dozen small cloven deer-hooves nailed to it. These trophies belong to a culture that loses confidence as it approaches a city, unless it approaches in a spirit of defiance, like the Countryside Alliance’s rally when the British parliament’s urban MPs abolished hunting with hounds, or the French farmers who drove a convoy of tractors up the Champs Elysées. The cultural differences here are greater than those that stem from needing to negotiate the presence of mud and small animals. Things that look chic in the city can look absurd in the country, while country manners can look unpolished in the city, where nonetheless tokens of ‘nature’ are admired, and where a shepherd’s naïveté can be taken to be an assurance that he is more in touch with real emotion than the more socially adept urbanite will ever be. There are different decorums in an urban and a rural milieu. Once these decorums have been established and learnt, we can switch between them quickly enough, and we know intuitively which one applies.3

Contrary to Hazlitt’s impression, everything comes from the country. All our food is grown there, and all our building materials are quarried or grown there. Once upon a time, of course, everyone lived in the countryside. The oldest cities seem to go back no more than 8,000 years (Çatal Höyük) and it is only in recent generations that urban populations have outnumbered those of the countryside, as industrial production methods have made it possible for food production to be maintained while rural areas depopulate. Once upon a time nearly everyone must have subsisted on what they or their neighbours grew to eat, and would have built their dwellings from local materials: timbers from the forest, stones from the fields, bricks of baked mud and straw. Even the small elite of feudal overlords would have known the places from where their sustenance came. Before industrialization no more than 10 per cent of the population lived in urban environments, even in the Roman Empire, which spread towns into places like Britain where they had previously been unknown. Even in the post-industrial United Kingdom, everything still comes from the country, but it is very likely that the countryside is not adjacent. Even fresh fruit and vegetables are routinely brought to the supermarket shelf from Kenya, South Africa, Israel or Peru, while rice from the foothills of the Himalayas, from Piedmont, the Camargue and China is in packets that sit beside one another for the shopper to select. Tea and coffee, which are so thoroughly ingrained in the habits of everyday life in the United Kingdom, are never grown locally, but have travelled from India and China, Indonesia, Malaysia, South America and East Africa. A packet that is branded ‘Yorkshire Tea’, and that shows a picture of rolling dales with dry-stone walls, is a blend of dried leaves that grew in Africa, India and Sri Lanka. We still need farmland, and we depend on the countryside as much as we always did, but where it is is anyone’s guess. If we go there, whether to the Yorkshire Dales or Sri Lanka, most of us will be on holiday, and in the United Kingdom the countryside makes most of its money from towns-folks’ leisure activities. In 2001 there was an outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease in the United Kingdom. The disease is very contagious, and was dealt with by culling infected animals and those on surrounding farms. Humans do not contract the disease, but they can carry it from one farm to another, so movement in the countryside was actually restricted in infected areas, and was generally cautioned against. Farmers were paid compensation for the animals they lost, but the rural economy was devastated because a much greater part of it was based on looking after visitors, who were suddenly no longer around. In these circumstances the food production, which was vulnerable to disease, had become a liability to the countryside’s principal economic activity, which turns out to be the management of scenery, and catering for those who come to see it. Recent figures put the proportion of people involved in agriculture, hunting and forestry in rural areas at 4.5 per cent, so the proportion directly affected by the threat to livestock would be significantly less than that, maybe 2 per cent, while those involved in hotels, restaurant and trade might be 15 per cent.4

Where building materials are concerned, we have gone through a similar process of disconnection. Before industrialization local building materials made for regional traditions, but now if we have regional variations it is more likely to be because of local by-laws, designed to preserve an appearance of tradition in the teeth of alternatives to it. The maintenance of tradition in buildings has moved from the realm of necessity and practicality to the realm of taste and culture. In places where the local by-laws do not specify local materials, the direct connection with the region’s immediate resources has long gone. The steel girders that structure Manhattan’s skyscrapers were made by smelting iron ore that came out of the ground in a rural area, but whether it was somewhere in the United States, Ukraine or China is difficult to say. It would depend on who could offer the best price, and the provenance would not inflect the design. The engineer and the architect would work together to determine the form and would specify the steel’s performance characteristics, and leave it at that. Plate glass was once sand, but from what desert did it come? The glass carries with it no memory of the place, and even when the glass is cladding skyscrapers in Dubai, there is little likelihood that it is a local material. MDF, the basis of much mass-produced furniture, was once timber, but treated in such a way that it has lost its grain and idiosyncrasies. Even when we make use of relatively natural timber, we expect to be able to specify dimensions and anticipate a regular, predictable product that has been standardized by a sawmill, and that will be straight and true. We are no longer in the position of feeling a need for timber and then going into the forest to look for a suitable tree to fell in order to meet our need. Nature and the countryside arrive on the urban building site as geometric shafts and sheets, or as heaps of cement and gravel.

At a practical level the links remain: the city is still dependent upon the countryside, but culturally it feels superior. What is a city? Lewis Mumford described the city as a theatre, where we see other people on the public stage, and where we act out our identities, partly to establish our place in the scheme of things, and partly so as to show ourselves who we are.5 In the United Kingdom today we expect a place that styles itself a city to be the centre of local government, have a university, a series of shopping centres and cinemas, at least one theatre, an abundance of restaurants offering cuisine from all over the world and more than one hospital. These features do not quite amount to a definition, but they are how we would generally recognize a city if we found ourselves in one. People living in the Roman Empire or medieval Europe had, within the context of their own time, expectations of what a ‘city’ should offer. In a much quoted passage, Pausanias dismissed the claims of urban status for a settlement in second-century Greece:

the city of Panopeus in Phokis: if you can call it a city when it has no state buildings, no training-ground, no theatre, and no market-square, when it has no running water at a water-head and they live on the edge of a torrent in hovels like mountain huts.6

Discussing this description of Panopeus, Moses Finley explained that Pausanias’ ‘audience would have understood. The aesthetic-architectural definition was a shorthand for a political and social definition’.7 The buildings mean that we readily recognize the city, but they are not what makes the city. The sociologist Philip Abrams warns us about what happens when we do not pay attention to our tendency to ‘reify’—to turn fluid and complex activities into simpler and more solid-seeming ‘things’. With reference to the modern context he writes:

The material and especially the visual presence of towns seems to have impelled a reification in which the town as a physical object is turned into a taken-for-granted social object and a captivating focus of analysis in its own right. Thus Harris and Pullman began an influential paper on the nature of the city by reacting in just that way to the immediately given urban phenomenon. ‘As one approaches a city and notices its tall buildings rising above the surrounding land and one continues into the city and observes the crowds of people hurrying to and fro past stores, theatres, banks and other establishments, one is naturally struck by the contrast with the rural countryside’.8

But the town and country were antithetical in the minds of ancient peoples too. A Roman relief sculpture juxtaposes the town of Avezzano, houses packed inside its walls, against the open countryside and its scatter of villas.9 A strong network of rural settlements supported the ancient city.10 The urban settlement sits at the apex of a continuum of development which leads us back to the hamlet and the isolated cottage. Clearly the city is not the same as the countryside, but it is linked to it, and the edge is not necessarily clearly defined. The search for a universal definition of urbanism has left many academic fields littered with the vanquished. We could try saying, for example, that cities are larger than villages, and most of the time this is true; but there were villages in nineteenth-century Russia which were bigge...

Table of contents

- Contents

- Illustration credits

- Contributors

- Preface

- Chapter 1 Rural and urban milieux

- Chapter 2 Villeggiatura in the urban context of Renaissance Rome

- Chapter 3 Rural urbanism

- Chapter 4 Anti-urban utopia in the Aufklärung

- Chapter 5 Urban meets rural

- Chapter 6 The picturesque bourgeois house at the edge of the neoclassical city

- Chapter 7 ‘Such a magnificent farmstead in my opinion asks for a muddy pool’

- Chapter 8 Nature and the city in 1920s America

- Chapter 9 Rurality as a locus of modernity

- Chapter 10 Is the kibbutz a ‘radiant village’?

- Chapter 11 An unlikely influence

- Chapter 12 From the ‘model village’ to a satellite town

- Index