Chapter 1

What is Knowledge Management?

INTRODUCTION

Knowledge Management (KM) is a key approach designed to aid superior decision making and solve current business problems such as competitiveness and the need to innovate in a dynamic, complex and global environment (Wickramasinghe and von Lubitz, 2007). The premise for the need for KM is based on a paradigm shift in the business environment where knowledge is now recognized as central to organizational performance (Drucker, 1993; Ichijo and Nonaka, 2007; Jafari et al., 2008). This macro-level paradigm shift also has significant implications upon the micro-level processes of assimilation and implementation of KM concepts and techniques (Swan et al., 1999), i.e. the Knowledge Management Systems (KMS) that are in place.

We are not only in a new millennium but also a new era. A variety of terms, such as the Post-Industrial Era (Huber, 1990), the Information Age (Shapario and Verian, 1999), the Third Wave (Hope and Hope, 1997) or the Knowledge Society (Drucker, 1999), have been used to describe this epoch. Whichever term is used, there is agreement that one of the key defining and unifying themes of this period is KM. However, nearly ten years into this new millennium still too many practitioners and researchers alike, not to mention students, struggle to understand “what is KM?”

Given the importance of KM to all business operations, irrespective of industry or geographical location, understanding KM has become an imperative for researchers and practitioners. This book is intended to dispel any myths and help the reader understand what KM is and what it is not.

KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT (KM)

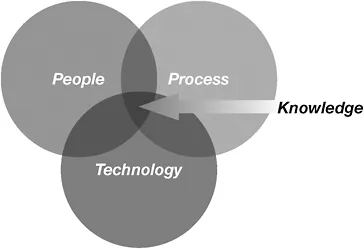

Central to KM is organizational knowledge, which exists at the confluence of people, process and technology (see Figure 1.1).

The key objective of KM is to create value from an organization’s intangible, as well as tangible, assets (Wigg, 1993). It is partly an amalgamation of concepts borrowed from numerous bodies of literature, including: artificial intelligence/knowledge-based systems, software

engineering, BPR (business process re-engineering), human resources, data mining management and organizational behavior (Liebowitz, 1999). However, it is important to note that while KM might have developed from the confluence of these numerous bodies of literature, KM itself is not BPR or data mining, and KM offers something new.

In essence then, KM not only involves the production of information but also the capture of data at the source, the transmission and analysis of this data, as well as the communication of information based on or derived from the data to those who can act on it (Davenport and Prusak, 1998). Moreover, unlike data management which typically focuses on organizing and refining data as a means to an end, or information management that is predominately concerned with structuring and categorizing information, integral to KM is the extraction of relevant data, pertinent information and germane knowledge to aid in superior decision making (Wickramasinghe and von Lubitz, 2007). The relevance of the data, the pertinence of the information and the germaneness of the knowledge are determined by the specific context.

HOW DID KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT COME ABOUT?

There are few who would argue that the current business environment is global as well as complex and dynamic. To survive in such an environment requires the attainment of a competitive advantage. Such a competitive advantage must be sustainable, i.e. difficult for competitors to imitate.

Sustainable competitive advantage is dependent on building and exploiting an organization’s core competencies (Prahalad and Hamel, 1990). In order to sustain competitive advantage, resources that are idiosyncratic (and thus scarce), and hence difficult to transfer or replicate, are of paramount importance (Grant, 1991). A knowledge-based view of the firm identifies knowledge as the organizational asset that enables sustainable competitive advantage, especially in hyper competitive environments (Davenport and Prusak, 1998; Alavi, 1999; Zack, 1999). This is attributed to the fact that barriers exist regarding the transfer and replication of knowledge (Alavi, 1999); thus making knowledge and KM of strategic significance (Kanter, 1999).

Since the late 1980s, organizations have embraced technology at an exponential rate. This rapid rate of adoption and diffusion of ICTs (information and communication technologies), coupled with the ever increasing data stored in databases or information that is being continually exchanged throughout networks, necessitates organizations to develop and embrace appropriate tools, tactics, techniques and technologies to facilitate prudent management of these raw knowledge assets; i.e. adopt KM.

Finally, during the late 1990s many organizations, especially in the U.S., have been experiencing significant downsizing and the reduction of senior employees. These employees over time have gained much experience and expertise and, as they leave their respective organizations, this expertise leaves too. In an attempt to stem the loss of expertise and vital know-how, organizations needed to embrace KM.

Taking together the need for a sustainable competitive advantage, the need to manage terabytes of data and information, and the need to retain vital expertise and knowledge residing in experts’ heads, organizations throughout the world are turning to KM solutions.

KEY CONCEPTS

In order to understand what KM is, it is essential to understand several key concepts. Since, KM addresses the generation, representation, storage, transfer and transformation of knowledge (Hedlund, 1990), the knowledge architecture is designed to capture knowledge and thereby enable KM processes to take place. Underlying the knowledge architecture is the recognition of the binary nature of knowledge; namely its objective and subjective components. Knowledge can exist as an object, in essentially two forms, explicit or factual knowledge, which is typically written or documented knowledge, and tacit or “know how,” which typically resides in people’s heads (Polanyi, 1958, 1966).

It is well established that while both types of knowledge are important, tacit knowledge, as it is intangible, is more difficult to identify and thus manage (Nonaka, 1991, 1994). Further, objective knowledge, be it tacit or explicit, can be located at various levels; e.g. the individual, group or organization (Hedlund, 1990). Of equal importance, though perhaps less well defined, knowledge also has a subjective component and can be viewed as an ongoing phenomenon, being shaped by social practices of communities (Boland and Tenkasi, 1995).

The objective elements of knowledge can be thought of as primarily having an impact on process. Underpinning such a perspective is a Lockean/Leibnitzian standpoint (Malhotra, 2000; Wickramasinghe and von Lubitz, 2007) where knowledge leads to greater effectiveness and efficiency. In contrast, the subjective elements of knowledge typically impact innovation by supporting divergent or multiple meanings consistent with Hegelian/Kantian modes of inquiry (ibid.) essential for brainstorming or idea generation and social discourse. Both effective and efficient processes, as well as the function of supporting and fostering innovation, are key concerns of KM in theory. These issues are critical if a sustainable competitive advantage is to be attained as well as maximization of an organization’s tangible and intangible assets.

The knowledge architecture recognizes these two different, yet key aspects of knowledge and provides the blueprints for an all-encompassing KMS (Wickramasinghe and von Lubitz, 2007). By so doing, the knowledge architecture is defining a KMS that supports both objective and subjective attributes of knowledge. The pivotal function underlined by the knowledge architecture is the flow of knowledge. The flow of knowledge is fundamentally enabled (or not) by the KMS.

In addition, it is possible to change from one type of knowledge to another type of knowledge and this too must be captured in the knowledge architecture. Specifically, as proposed by Nonaka (1994), there exist four possible transformations: 1) combination—where new explicit knowledge is created from existing bodies of explicit knowledge, 2) externalization—where new explicit knowledge is created from tacit knowledge, 3) internalization—where new tacit knowledge is created from explicit knowledge, and 4) socialization—where new tacit knowledge is created from existing tacit knowledge. The continuous change and enriching process of the extant knowledge base is known as the knowledge spiral (Nonaka, 1994).

Once the knowledge architecture has been developed, it is then necessary to consider the knowledge infrastructure. The knowledge infrastructure consists of technology components and people t...