![]()

PART I

UPWARD

Diving In, Non-Seeing

![]()

A SCENOGRAPHY OF LOVE

with Deb Verhoeven

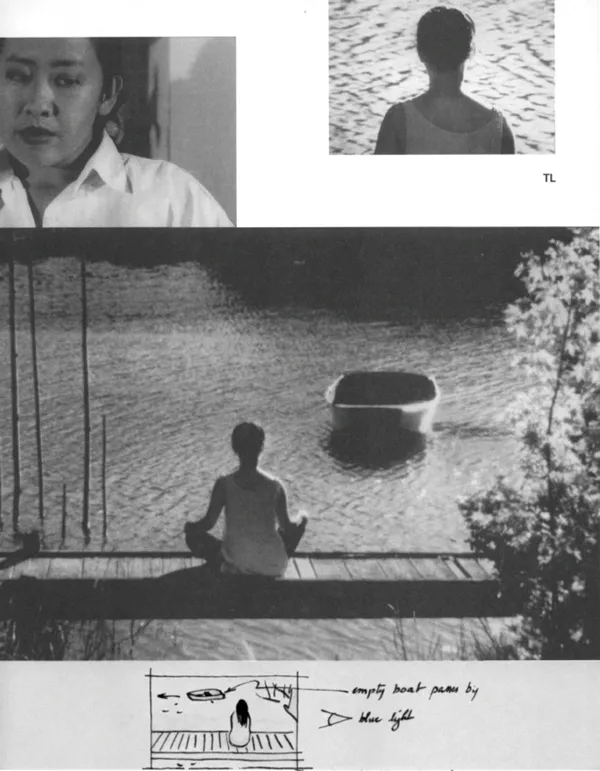

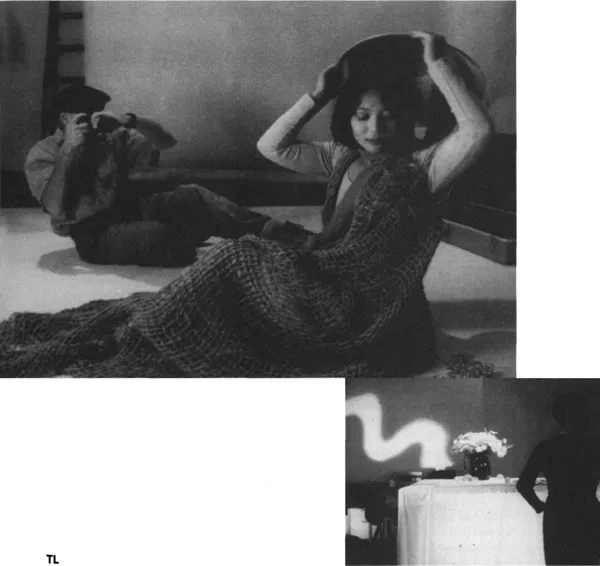

A shortened version of this interview was first published in World Art, No. 14 (August 1997) with the following introduction by Deb Verhoeven: “The man who played an instrumental role in creating the idea of the screen lover, Marcello Mastroianni, described the love story itself as inherently difficult and invariably unnatural. ‘The real language of love,’ he said, ‘is an inarticulate thing.’ The difficulty of love stories is, in this sense, a formal rather than emotional matter. For Mastroianni, the language of love is never carried in words per se but can be experienced in the silver of a lover’s breath, in the quickening of its rhythms. Trinh T. Minh-ha’s most recent film, A Tale of Love, is also premised on the idea that love stories rarely capture the true experience of being in a state of love. The film was in part inspired by an epic Vietnamese poem, ‘The Tale of Kieu,’ written by the early-19th-century poet Nguyen Du. In Trinh’s film, the story of a sacrificial woman who supports her family by resorting to prostitution has been extrapolated to the Vietnamese-American migrant experience. Trinh’s latter-day Kieu is a freelance writer and photographer’s model who sends money to her family in Vietnam. She is also in love with Love. It is Kieu’s meditations on love—her conversations with her photographer, Alikan, and her friend Juliet (who firmly believes her Romeo will come)—that eventually unmask the gender issues she shares with her 19th-century namesake. What particularly marks A Tale of Love’s unique contribution to the cinema is Trinh’s experiment with many of those ‘formal’ difficulties inherent to the love story. Trinh has disconnected and intensified the visual and aural vernacular at her disposal in order to capture the unadulterated and elemental sensations that characterize a state of being in Love. The film presents to its audience partial views, saturated colors, elliptical narratives, sounds separated from context A Tale of Love is a film that must be savored, but in the savoring there is always the unsettling knowledge of absence, of loss, and even perhaps of sacrifice.”

Verhoeven: I would like to begin on a self-reflexive note—with a discussion about the importance of the interview itself in your work. Unlike many filmmakers who see the interview as an unhappily necessary aspect of the publicity machine, it seems that you have elevated or emphasized the value of the interview in your films and publications. You use interviews in a quite complex way, especially in Surname Viet Given Name Nam in which you stage performances based on previously published interviews. And even in the film that lends itself most easily to the description “fiction,” A Tale of Love, you include detailed dialogue exchanges that revisit the structures and shapes of the documentary interview. Could you comment on the reasons for your interest in the interview process?

T: The interview can certainly be an art, but it is also just one among the many possible forms of relating. I cannot say I’m interested in elevating it or emphasizing it. As with any structure that shapes one’s activities—even momentarily—one cannot use it without being used by it, so I would rather explore and push it to its limits than ignore or take it for granted.

Questions and answers can sometimes force both interviewer and interviewee into awkward positions because we often feel compelled to bear the burden of representation. We know we are not simply speaking to each other or for ourselves; we are addressing a certain audience, a certain readership. And since we are framed by this question-and-answer mechanism, we might as well act on the frame. If we put aside the fact that the popular use of the interview is largely bound to an ideology of authenticity and to a need for accessibility or facile consumption, I would say that the interview is, at its best, a device that interrupts the power of speaking, that creates gaps and detours, and that invites one to move in more than one direction at a time. It allows me to return to my work or to the creative process with different ears and eyes, while I try to articulate the energies, ideas, and feelings that inspire it. It is in the interval between interviewer and interviewee, in the movement between listening and speaking or between the spoken word and the written word, that I situate the necessity for interviews.

In Chinese painting, Line is action; it is Form’s frontier. You have given me here a very interesting line to open with, by linking the question about the interview to the dialogue exchanges in the film A Tale of Love. I did not think of the film’s dialogues in quite the same terms, but your question reminds me that among the more recent poems I’ve written, there is one actually titled “Diamonologue.” Since I’ve always worked at the crossroads of several genres and categories, it’s true I’ve often been attracted to what one can call border terms, border texts, border sounds, border images. I’ve been told time and again in interviews or in public discussions that my “answers” to the questions asked are more like mini-lectures, that they characteristically touch on about five different issues at once. It’s difficult for me to stay within the confines of a setup that often does not correspond to the way I think. I have to find a satisfactory way to address the question raised; satisfactory in that it gives something both to the listener and to myself. So it’s important in interviews to let one’s thoughts come to oneself of their own accord since the aim is not simply to provide answers, but to keep desire, the interval, alive.

When I wrote the script of A Tale of Love, I did not want to write mere dialogues. What comes out, hopefully, are not simply questions, answers, opinions, reactions, and so on between two people, but verbal interactions that lie between the soliloquy and the conversation. True, this is the way I’ve also been working with interviews, slightly enhancing their inevitably fabricated effect rather than hiding it. Both duration and interruption are necessary for certain things to emerge. The verbal events in A Tale are at the same time interactive and independent of one another. Each unfolds according to its own story, its own logic. There’s no good or bad. I was indifferent to the tradition of psychological realism and was creating dialogues and characters that were not quite dialogues and characters. I used actors, but was interested in the intensity of a veiled theatricality, not in naturalistic acting. And what appeared as conflict never got resolved because there was truly no real conflict in the film. So the story I offer turns out to be in the end just a moment of a no-story.

V: A Tale of Love was described as your first feature narrative—to which you have responded that you neither agree with the terms “first,” “feature,” or “narrative.” How then would you prefer to describe your most recent film?

T: The combination of these three terms subjects the film to a hierarchy, a category, and an order imposed from the outside, that is, from a tradition of making narrative and advertising it as a “special attraction” that has little to do with the film’s own workings. “First” in relation to what? If it is in relation to my own artistic itinerary, then yes, everything I come up with is a “first.” But if it is a question of making a debut in the art of storytelling, then no, because there are ten thousand ways to tell stories. I could never conform to an all-plot, action-driven narrative dictated by the mass-media model, with its unity of theme, time, place, and style, or with its clarity of story line, dialogue and character. I would rather work with film the way, for example, Heinrich Von Kleist describes marionettes and their unequaled dance movements: You find the centers of gravity as they emerge with the work, you give all your attention to where the weight falls, and the rest follows of its own accord.

The film is put together as a multiplicity of movements. Each movement has its centre of gravity; and centers do move, they are not static. This is very close to the notion of ch’i-yun (or spirit-breath-rhythm) that determines the vitality of a work and is the artist’s sole aim in Chinese traditional arts. It’s so easy to fall prey to what Raul Ruiz calls the “predatory concept” of cinema, a normative system of ideas that enslaves all other ideas that might slow down, distract, rupture, or put obstacles in its activity. Because of this exclusive form of centering, no human can come anywhere near a puppet, for Von Kleist, where grace is concerned. This can apply to A Tale, both literally or negatively, on the level of acting, and figuratively or positively, on the level of narrative structure. Acting, never free of affectation, should subtly be seen as acting. By subjecting all elements of cinema to serving the plot and to psychological realism, one simply buys into the normalized practice of commercial cinema, which can see multiplicity only as a threat. If I refuse such a classification as “first feature narrative” for A Tale, it is to invite viewers to come up with other ways of experiencing film. How they name and describe this experience is ultimately up to them as the naming also tells us about them as viewers.

V: Why choose “the love story” as a key point of departure for the film?

T: As a poet puts it, “Experience is an interval in the body” [Mei-mei Berssenbrugge]. It’s such a precise statement and, for me, full of love. On the one hand, there’s no cinema—only entertainment, document, information, technique, for example—if there’s no love. On the other, the entire history of narrative cinema is a history of voyeurism, and no matter what form it takes, the art of narrative cinema is unequivocally the art of resurrecting and soliciting love. A friend of mine once said that “all the books written and stored in the libraries are in fact one single book.” You can never capture love or death on film, they are what I call, in A Tale, the two Impossibles. This applies to both fiction and documentary films the difference between which is more a question of degree. Death is a name by which we draw a limit to the unknown. Death is not bodies falling into a pool of blood, for example; nor is it cadavers, mummies, skulls, or skeletons on display. Death is in every moment of life; it is, crudely speaking, something we live with the moment we step into life. So although there’s nothing more old-fashioned than narratives of love, we continue to produce and consume what, in the widest sense of the term, always comes down to the love story. And surely, what is characteristically sought after in societies of consumption is the exceptional-individual love story.

V: In press material you write that A Tale of Love “offers both a sensual and intellectual experience of film.” Would you also expect that the film be an emotional experience for the audience? You detail the sensual experience of love as a state of heightened impressions, a heightened separation of elements. Would this also apply to the emotional experience of love? Can these terms “emotional,” “sensual,” and “intellectual” themselves be meaningfully separated?

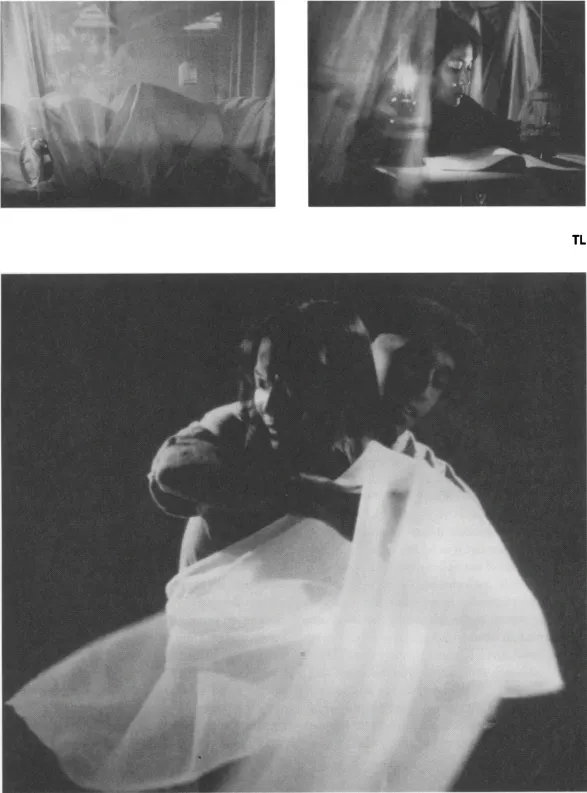

T: Not really. These are all ambiguous terms that designate different spaces. What is emotional changes radically with each viewer. I’ve been told by many that they were very moved by the film, but I’ve also heard comments from the audience that suggest how difficult it is for them to identify with my characters, or rather, noncharacters, and how distanced they feel toward them. Of course, this does not necessarily exclude the fact that the film can still be moving. It all depends on what the viewer really sees and hears. Gertrude Stein’s “A sentence is not emotional a paragraph is” always makes me smile. I would say that in A Tale, more than in my previous films, what is visible and audible can prevent one from seeing and hearing. What continues to elude us is the fact that the image is in itself a veil; so is the “dialogue,” especially when it appears all too obvious at first reception.

When I resort to the distinction made between sensual and intellectual, it is to recall something very basic to the experience of film. If I define cinema as an alchemy of the fragment or an art of the cut—this means one learns when, how, what to cut, not simply by following the script one wrote or media formulas, but intuitively, in the way one conceives image, sound, and silence. If it is the art of the cut rather than that of the suture, then filmmaking is no more the putting together than the pulling apart of fragments. Less a question of consolidating power through unity and coherence, than of transforming at the base with incisive cuts, instinctive distractions and sharp discontinuities. To follow an idea, a story, or a message is primarily an intellectual activity, especially in the context of film where the active reconstruction of fragments and details is constantly at work, if one is to “understand” what is being shown. But the experience of film is also a sensual one, as the reception of images and sound appeals immediately to one’s senses before one makes sense of them. Pudovkin did not hesitate to affirm that film is “the greatest teacher because it teaches not only through the brain but through the whole body.”

Yet films that resist serving up a story or a message without merely falling into the trap of serving Art, often leave the spectator at a loss. For me, since brain and body are not separable—despite the fact that society, as suggested in A Tale, still largely prefers women’s bodies without their heads—the nonverbal events in the film and what is not sayable in the actors’ dialogues are just as important, if not more, than what is actually said. Often, people who have problems with the content or the performance of A Tale and whose rejections can sometimes be fiercely anti-intellectual (not to mention sexist), are precisely those whose viewing of the film remains primarily intellectual. Such a viewing never accounts for the impact of a film on the spectator’s body. It reduces everything to the order of meaning and remains oblivious to the way the nonverbal, plastic, musical, sculptural, or architectonic workings of a film interact with its content and verbal performance. For me, a sensual experience is clear and luminous, but not immediately tangible; you don’t know where you are exactly, so you take a risk when you try to verbalize it.

I’ve made a detour to come back here to precisely what the film focuses on: an altered state of the mind and body, the state of being in love, in which our senses are strangely aroused and sillily obscured—hypersensitive; so lucid and so blind at the same time.

V: At the end of A Tale of Love Kieu comes to a realization that her own narrative comprises a series of layers without the “climax” or unifying flourish that ordinarily conclude the conventional “love story.” The point is that she “recognize” her own situation, gaze upon it and so “be in love with love—not with a Prince Charming.” Then there can truly be a happy ending. How might this observation be applied to the cultural rendering of Kieu—as a metaphor for Vietnam?

T: There’s no truly happy ending; I didn’t intend to imply this. But your question is a real challenge, because if Kieu as a literary and mythical figure has been the site of continuous moral and political appropriation in Vietnamese culture, it was more in relation to foreign domination in Vietnam’s history and to the Confucian norms that regulate women’s “proper” behavior. The conclusion of being in love with Love is one that I introduce in my own tale, one that is informed by the feminist struggle and its questioning of power relationships exerted in the name of love. Kieu’s tumultuous and wretched love life, her being forced into prostitution, her passion and sacrifice have all been extensively written about and used as an allegory for Vietnam’s destiny. But no one has really linked Kieu’s denouement to Vietnam’s geopolitical, socioeconomic, or artistic and ethical situation today. Perhaps I can venture into saying that independence entails complex forms of re-alignment, and that Vietnam’s opening up, which for many means assimilation of the free West, can be, despite all the mistakes and drawbacks, a way of keeping Her distance from all three power nations: China, Russia, and the U.S. Infidelity to others and to one’s own ideals, even when dictated by circumstance, can only lead to difficult places, and hence, there’s definitely no simple happy ending here.

V: A Tale of Love explores the premise that a character/person can have many stories and many selves. Do you consider that you have many selves? What are they? There is a moment in the film where the characters discuss the idea that women in particular are punished for having many talents—is this true of your own experiences?

T: It’s by working with multiplicity that the notion of “character” can be undone. Since the narrative was not conceived as a game of psychological construction, it was important that everyday individualized passions should not be the mainspring of the film, and that each of the protagonists (Kieu, Juliet, Alikan, the Aunt, Minh) should be a multiplicity. They are what one can call disinherited characters, and the actors cannot simply “act themselves.” For me my many selves are as real as the fingers of my hand, although the process of naming them can be infinite, if I were to avoid types, roles, and fixed categories. Kieu’s miseries have been legendarily attributed to her beauty and her many talents. Although I don’t necessarily identify with her, Kieu’s life does speak to the lives of innumerable women.

In my case, it has always been extremely difficult. We live in a very compartmentalized world, and people certainly do not forgive you for being more than one thing at a time. Aside from the fact that as a woman, you always have to be twice as excellent for them to accept you simply as “proficient,” they also cannot praise you, for example, as an artist without demeaning you as a theorist or a scholar, and vice versa, depending on where the stakes are for each of them. The more accessible I look, the more competitive they tend to be. Age, gender, ethnicity, and appearance have a lot to do in these kind of situations. This holds true even for my closest friends, some of whom simply can’t accept my being, independently, every bit as much a writer as a filmmaker, and vice versa, for example. They prefer to give you credit for the area that is clearly not theirs or where t...