1

CONSIDERATIONS ON THE EMERGENCE OF ORGANIZATIONAL COACHING

International perspectives

Michel C. Moral and Sabine K. Henrichfreise

INTRODUCTION

If many books have been written addressing organizational change, very few mention organizational coaching. None provides frameworks and perspectives that can assist coaches working in multinational companies or on cross-border challenges. Most approaches rely on either the Organization Development (OD) paradigm (Lewin 1947; McGregor 1971) or the Corporate Culture Change methods (Schein 1985). Models were either ‘commitment based’, trying to convince employees and middle management by showing positive images of the future, or ‘compliance based’, changing behaviours by imperatives. These models only go so far in providing guidance and clarity for coaches immersed in the complexity of global business. The two authors have published a book on this subject in France (Moral and Henrichfreise 2008). This chapter summarizes its key ideas and includes new international experiences from their organizational coaching activities.

Coaching for executives and high potential managers developed in the USA and in Europe during the 1980s. Team coaching for executive boards or for project leading teams started to be a reality at the beginning of the 1990s. Logically, organizational coaching should have emerged early in the millennium. In fact, its development has been slowed down by the existence of several strong ‘compliance based’ methodologies like, for instance, business process reengineering (BPR) (Stewart 1993) and performance management. These methodologies assume a top-down approach with an ‘external expert’ or ‘guru’ role for highly paid consultants. They give token attention to inclusive, action-learning approaches which position organizational players at all levels and locations with shared responsibilities for change. It is in this latter kind of organizational change paradigm that executive coaching is starting to have an impact and which is the focus of this chapter.

CHANGES IN THE ENVIRONMENT

The organizational challenges face top level management and the executive coaches who they are increasingly engaging to assist them. Invariably, these challenges have strong international dimensions, often related to shifting labour markets. With the rapid development of Chindia (China-India) during the last decade, Western countries are facing a situation where one billion new workers are potentially available all over the planet at a very low salary rate. In order to cut production and administrative costs, the occidental multinational companies are moving their workloads to countries where infrastructure and personnel costs are low. More and more plants, call centres and administrative tasks are implemented in Eastern Europe, Asia, Africa or Latin America. Market changes are now very fast, and competition between enterprises is looking more like a kayak race in the rapids, rather than a rowing contest on the Thames. If they want to be effective, coaches need to be informed about such trends. Plus, they need to be professionally and personally equipped to deal with international and organizational ‘white water’. The concepts and examples that follow may be of assistance.

RECENT APPROACHES TO ORGANIZATIONAL CHANGE

If we consider the many theories of organization, from the very beginning, with Frederick Taylor and Henri Fayol, to the most recent ones, we eventually come to representing an organization as a system interacting with its environment. Within this system, four subsystems are possible entry points when one considers triggering a change:

- The corporate culture. Many authors have considered changing the organization by changing its culture: Edgar Schein, of course, but also Ronald Burt (1999), John Kotter and James Heskett (1992), Gareth Morgan (1989), Millward (2003), Weick and Quinn (1999), Giroux and Marroquin (2005), etc.;

- The corporate structure, which is more or less represented by a combination of the organization flowchart and the corporate processes, both being implicit or explicit depending on the country and the activity;

- The information technology, which is providing new opportunities not only in terms of communication between people, but also in terms of managing data, to extract from it information and perhaps knowledge. Originally, the Socio-technical System Theory (STS) (Trist and Bamford 1951) considered the tight relationship between the social and the technical systems. Recent technology development makes it possible to have organization patterns that were beyond our imagination a few years ago. Not only is the functional structure, designed by Frederick Taylor in 1911, finally possible to implement, but also, since then, a multitude of other organizational layouts have been created. Enterprises are more and more like cyborgs, half human, and half cybernetics; and

- The decision system, which carries objectives to execution, usually from top to bottom.

This four-subsystem representation is similar to how Dr Tony Grant at the University of Sydney (Grant and Greene 2003) identifies four elements in the coaching process:

- behaviours (equivalent of the decision system above);

- emotions (corporate culture);

- situation (structure); and

- cognition (technology).

There are tight interactions between the four subsystems. Acting on one of them usually strongly impacts on the three others. Any change process that takes account of only one subsystem is doomed to fail because resistance will be overwhelming. The message is that while there are four potential entry points, it is necessary to traverse all four subsystems to facilitate sustainable change. Let’s look at an international example.

A medium-sized European company, specializing in telecommunication systems, decided to develop its business in the Americas and in Asia. A group of consultants recommended working on their corporate culture (i.e. subsystem 1 above), and a number of seminars were held with the different divisions—run by outside consultants. The objective was to develop a new set of values and behaviours. Resistance was high. The process did not work and the enterprise pursued its development unchanged. Later on, an organization manager was hired. He immediately noticed that the prevalent forces were the executives in charge of product lines. Also he noticed that the distribution managers, organized per geography, had limited power. He proposed shifting a number of key responsibilities from the product lines to the distribution lines. For instance, the decision to promote and increase the salary of the marketing groups was transferred to the distribution executives. The executive in charge of developing business in the Americas and in Asia became a king in an instant, and his first-year achievements far surpassed business objectives. The initiative was done in tandem with further and related virtual seminars on corporate culture and structure. These were run by managers with the assistance of executive coaches. The power of the intervention came from the fact that it interactively worked across subsystems 1, 2, 3 and 4.

RESISTANCE AS AN OPPORTUNITY

According to Tannenbaum and Hanna (1985) resistance is due to the lack of closure which prevents organizational members letting the past go. Another view is that change may create a threat to self-esteem (Jetten, O’Brien and Trindall 2002). Also, the analysis of potential gain and loss by people has been considered by Prochaska, Redding and Evers (1997) as a good predictor of resistance. But, the research on resistance and organizational inertia is insuficient overall and urgent attention is needed from the community of researchers.

What we know for sure is that resistance to change is inevitable, but not unhealthy. In the outside expert model, those who resist are often viewed as ‘not getting it’ and either demonized or excluded from the processes of change. In the complex international systems which make up large contemporary corporations, such approaches make little sense. Executive coaches who are savvy in such systems use resistance as information and as energy to accelerate the transformation. Coaches expect resistance and their sole concern is how to use it. Those who initially resist are engaged within the system (although some may need to leave the organization if they will not or cannot work with the transformation).

AN ANALOGY WITH PHYSICS

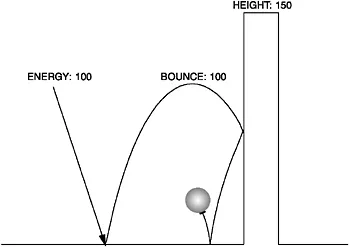

Physicist Louis de Broglie had the idea of ‘matter as wave’ and a consequence of this concept is what is called the ‘tunnel effect’. Unlike the classical mechanics of particles, quantum mechanics allows light as well as particles (such as electrons and protons) to appear even where the ‘wall’ of potential should prevent them from appearing. The analogy of tennis balls being bounced over a brick wall illustrates the effect of particles tunnelling through walls of potential (see Figure 1.1). Imagine thousands of tennis balls (representing particles) being simultaneously thrown to the ground with a given energy in each ball of, say, 100 units. The maximum bounce of each ball is 100 units. If the wall is 150 units high, logically no tennis ball will bounce over the wall. But, quantum mechanics demonstrates that particles with energy lower than the wall of potential can go through it. More precisely, some of them, not all of them, will appear on the other side. This is called the ‘tunnel effect’ because it is as though there were a hole or a tunnel in the wall of potential, allowing some of the particles to pass through it. According to quantum mechanics, matter with appropriate energy can go through the wall, since particles, as well as light, have particle–wave duality. Waves, according to Schroedinger’s equation, can do what particles, according to Bohr’s laws, cannot.

Figure 1.1 Tennis ball analogy of the tunnel effect

In our tennis ball illustration, the scenario would be that a bunch of some 10,000 tennis balls is thrown on the ground with energy of 100, and that some of them would reach the other side of the wall. Tennis balls are not dual and therefore remain as matter. But, there are interactions between the balls inside this chaos of 10,000 tennis balls bouncing around everywhere. Some energy can be transferred by several balls to others, which then have enough impulse to fly over the wall.

However, it is our purpose to discuss organizational coaching, not physics or tennis. The tunnel effect is potentially a very useful concept for coaches working with executive clients who are facing very high and solid walls of resistance to vital change processes.

LOOKING FOR A TUNNEL IN THE PROCESS OF ORGANIZATIONAL COACHING

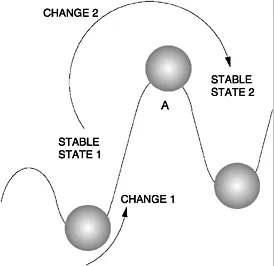

There are walls of potential—in the form of resistance—in all coaching, as shown in Figure 1.2, and it is much higher when we deal with international organizations. (As noted earlier, high-impact coaching views resistance as potential.)

Coaching helps a client change. Systems Theory considers that there are two levels of change. The first level of change (change 1, in Figure 1.2) is limited to do more of the same, for instance automate the processes to increase productivity and make more money. The second level of change (change 2, in Figure 1.2) is a shift of paradigm, for instance re-engineering the processes to access totally new areas of business and to double income.

Figure 1.2 Levels of change

To achieve a second-level change, the client has to reach a point (shown as A, in Figure 1.2) where everything becomes uncertain. A change of this nature requires considerable energy. For instance, a married couple may be in a stable state (state 1) in their relationship. Before they decide to have a baby (state 2), there are often months of discussion, contemplation and hesitation.

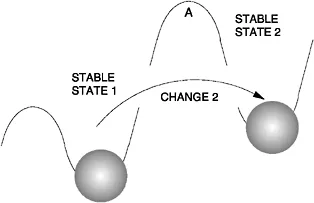

In international organizations, high and solid walls of resistance/potential exist between state 1 and state 2, i.e., between the current state and the desired state. In individual and team coaching, it is not a big issue because the height of the wall is usually not that intimidating and we have now developed sophisticated coaching tools to jump over or remove most of them. In organizational coaching, the walls are high, very high—and solid. The challenge for coaches is to find and utilize methodologies to work with organizations to harness energy and produce a tunnel effect which would allow change processes to proceed through the various walls (see Figure 1.3). The alternative of trying to knock down the walls requires and saps organizational energy. Plus, it is unlikely to work—primarily because the resulting conflict will generate further resistance and higher walls. (Some conflict is, of course, a necessary part of any change process.)

Figure 1.3 Tunnelling from state 1 to state 2

THE TUNNEL

Our experience with enterprises demonstrates that we need to distinguish three categories of situations. The first one, illustrated in Figure 1.4, is the purely hierarchical organization: each person has only one manager.

Such organizations still exist. They are quite happy with normative change methods, as the vertical descending flow from objectives to execution usually works well. Bottom-up approaches are problematic because of the resistance factor, and pilot approaches are not very successful, due to the ‘not invented here’ syndrome. Probably the good old OD is still the best to trigger a change 2, to a matrix organization.

The second category of organization is the matrix, as shown in Figure 1.5. In these organizations, the main concern is reactivity to market changes. It is like a rowboat trying to react like a kayak in the rapids. Frequently, the decision system generates so many layers of control and such a level of uncertainty and frustratio...