eBook - ePub

Thinking about Democracy

Power Sharing and Majority Rule in Theory and Practice

- 305 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Arend Lijphart is one of the world's leading and most influential political scientists whose work has had a profound impact on the study of democracy and comparative politics.

Thinking about Democracy draws on a lifetime's experience of research and publication in this area and collects together for the first time his most significant and influential work. The book also contains an entirely new introduction and conclusion where Professor Lijphart assesses the development of his thought and the practical impact it has had on emerging democracies.

This volume will be of enormous interest to all students and scholars of democracy and comparative politics, and politics and international relations in general.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Thinking about Democracy by Arend Lijphart in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Political History & Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Introduction

1 Introduction

Developments in power sharing theory

The present volume contains articles and chapters written over a period of thirty-five years, from 1969 to 2004, but most of them date from the 1990s. They all evolve around the idea of power sharing democracy, its different forms, alternative democratic institutions, and other closely related topics. In this Introduction, my emphasis will be on the intellectual development of power sharing theory and on the cohesion among its components. The essays that I selected for inclusion in this volume constitute only a small portion of my total scholarly output, and in the Introduction I shall explain why I regard them as the most representative and significant of my work. It will also give me an opportunity to express further thoughts on these topics as well as a few second thoughts that I have had.

Consociational democracy

My article on ‘‘Consociational Democracy,’’ published in 1969, is often regarded as the ‘‘classic’’ statement of consociational theory. It is mainly for this reason that I chose it as the first essay to be reprinted in this book (in Chapter 2). It is still frequently cited, and it was selected by the editors of World Politics in 1997 as one of the seven most important articles that appeared in the first 50 years of this journal. Strictly speaking, it was not the very first statement of consociational theory. I had already introduced the basic concept in my case study of the Netherlands, The Politics of Accommodation (Lijphart 1968a), and it was also included as part of my broad survey of the literature on typologies of democratic systems published in the same year (Lijphart 1968b); in that article, I used the term ‘‘consociational’’ for the first time.

In this connection, I should also point out that neither this term nor the general concept were entirely new. I borrowed the term ‘‘consociational’’ from David Apter’s 1961 study of Uganda, and it can actually be traced as far back as Johannes Althusius’ writings in the early seventeenth century; Althusius used the Latin consociatio. Both of these sources are acknowledged in the ‘‘Consociational Democracy’’ article, as is Gerhard Lehmbruch’s 1967 monograph on ‘‘proportional democracy’’ – roughly similar to consociational democracy – which preceded my Dutch case study by one year.1 I later discovered other precedents: in particular, Sir Arthur Lewis’ monograph Politics in West Africa (1965) – the first modern scholarly exposition of consociational theory, to which I shall return in the Conclusion – and the writings of the Austro-Marxists Otto Bauer and Karl Renner in the early years of the twentieth century.

In subsequent writings, I gradually refined my analyses in several ways, but my descriptions and definitions have remained stable since the 1990s. One reason for choosing my 1996 case study of India as the next chapter – apart from the intrinsic significance of the Indian case – is that it contains my ‘‘final’’ formulation of consociational theory. Compared with my writings of the late 1960s, I made five significant improvements. One was to define consociational democracy in terms of four basic characteristics – grand coalition, cultural autonomy, proportionality, and minority veto – listed in the first paragraph of the India article and discussed at length later on. Only the first of these was extensively discussed in my 1969 article. Second, I now usually make a distinction between primary and secondary characteristics: grand coalition and autonomy are the most crucial, whereas the other two occupy a somewhat lower position of importance.

Third, I now always emphasize the fact that all four consociational features can assume quite different forms but, at the same time, that these different forms do not work equally well and are not equally to be recommended to multi-ethnic and multi-religious societies that are trying to establish consociational institutions. For instance, in the ‘‘Consociational Democracy’’ article, I describe the varieties of grand coalitions that have been formed, and elsewhere I have described the different ways that the principles of autonomy, proportionality, and minority veto can be implemented. One general recommendation can be made in terms of the traditional categories of constitutional engineering. While consociational democracy is not incompatible with presidentialism, plurality or majority electoral systems, and unitary government, a better constitutional framework is offered by their opposites: parliamentary government, proportional representation (PR), and, for societies with geographically concentrated ethnic or religious groups, federalism. In Chapters 9 through 14, the parliamentary-presidential and plurality-PR contrasts are discussed at greater length. Another general recommendation is that consociational institutions and procedures that follow the principle of what I have called ‘‘self-determination’’ are superior to those that are based on ‘‘pre-determination’’ – discussed at length in Chapter 4.

Fourth, my ‘‘Consociational Democracy’’ article presents only an initial and tentative analysis of the conditions that favor the establishment and survival of consociational systems. On this aspect of consociational theory, my conclusions have undergone a series of adjustments as I explored additional cases and as I listened to the advice of both critics and sympathetic readers. However, from the mid-1980s on, I have settled on a list of nine favorable conditions, which can be found in my article on India. Moreover, I now always list the absence of a solid ethnic or religious majority and the absence of large socioeconomic inequalities among the groups of a divided society as the two most important of these nine favorable factors. Finally, a point that I generally emphasize when recommending consociationalism as a solution to ethnic conflict is that the nine conditions should not be regarded as either necessary or sufficient conditions: an attempt at consociationalism can fail even if all the background conditions are positive, and it is not impossible for it to succeed even if all of these conditions are negative. In short, they must be seen as no more than favorable or facilitating conditions in the common meanings of these terms.

In my 1969 article, my main examples of consociational and partly (or temporary) consociational systems are the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, Austria, Switzerland, Lebanon, Nigeria, Colombia, and Uruguay. I have gradually discovered and analyzed other cases, and in my book Democracy in Plural Societies (Lijphart 1977), the new cases are Malaysia, Cyprus, Suriname, the Netherlands Antilles, Burundi, Northern Ireland, and the two semi-consociational systems of Canada and Israel. In my article on India as a consociational democracy, I also briefly mention CzechoSlovakia and South Africa. More recent examples are Fiji, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Macedonia, Kosovo, and Afghanistan.

Of all of these cases, however, India is by far the most important for four reasons: First, it is one of the world’s most deeply divided societies, and divided along both religious and linguistic cleavages. Second, it is an almost perfect example of consociational democracy, exhibiting all four of its characteristics in clear and thorough fashion. Third, with the exception of the short authoritarian interlude of the Emergency in 1975–77, it has a longer history of continuous democracy and a better democratic record than any other country in the developing world. Fourth, its large population of more than 1 billion people – larger than the populations of all of the other cases combined – makes it an especially important example. The one qualification is that, as I note toward the end of my analysis of India, consociationalism declined to some extent from the late 1960s on. I made this judgment in 1996 and I clearly feared at that time that consociationalism, and hence also democracy, in India was at risk. I now believe that I was far too pessimistic. In particular, the decline of the Congress Party has actually made the consociational system stronger because the dominant-party system and frequent one-party cabinets have been replaced by an extreme multiparty system and very broad coalition cabinets that often include more than a dozen parties. Moreover, the diminished status of the Congress has made its centralized and hierarchical features less important for the system as a whole, while inside the party these tendencies have also weakened. Federalism has been strengthened a great deal, and minority educational autonomy, separate personal laws, adherence to proportionality, and the minority veto are all still intact.

I have already briefly alluded to my essay on self-determination and predetermination (Chapter 4). These rival concepts, and my conclusion that self-determination was the more desirable principle on which to organize consociational rules and institutions, were developed as a result of the challenge that I and other consociationalists faced in the 1970s and 1980s to propose an optimal consociational design for the unusual South African conditions: identifying the constituent groups in this country was both objectively difficult and politically controversial. Self-determination may be called the ‘‘agnostic’’ approach to ethnicity and divided societies: they allow us to ‘‘agree to disagree’’ about which groups should be identified as the essential participants in consociations, and even about the contentious issue of whether a country like South Africa can be accurately described as a divided society or not. Election by PR, which is the main self-determination method, permits the emergence and political representation of any group – ethnic or non-ethnic, religious or non-religious – and is not biased for or against ethnic and religious parties. Another advantage is that it promotes the flexible adjustment of power and representation in response to any changes in the strength of ethnic groups, as well as the flexible adjustment to any decline in the overall strength of ethnicity, the growth of a more homogeneous society, and the emergence of non-ethnic and non-religious parties.

Consociational and consensus democracy

In my writings after 1969, I started using the term ‘‘power sharing’’ democracy more and more often as a synonym for consociational democracy. The main reason is that I started to use consociationalism not only as an analytical concept but also as a practical recommendation for deeply divided societies. The term ‘‘consociational’’ worked well enough in scholarly writing, but I found it to be an obstacle in communicating with policymakers who found it too esoteric, polysyllabic, and difficult to pronounce. Using ‘‘power sharing’’ instead has greatly facilitated the process of communication beyond the confines of academic political science.

I have also often used power sharing as a rough synonym for the concept of ‘‘consensus democracy,’’ which grew out of my effort to define and measure consociational democracy more precisely. The result, however, was a new concept that, while still closely related to consociational democracy, is not coterminous with it. Because I use both concepts in my essay on ‘‘Constitutional Design for Divided Societies’’ (Chapter 5) and the concept of consensus democracy exclusively in my chapter on ‘‘The Quality of Democracy,’’ taken from my 1999 book Patterns of Democracy (Chapter 6), I need to explain the differences between the two concepts here.

The two are closely related in the sense that both are non-majoritarian forms of democracy. The differences can largely be accounted for in terms of how they were derived. As is clear from my ‘‘Consociational Democracy’’ article (Chapter 2), the concept of consociationalism arose out of the analysis of a set of deviant cases where stable democracy was found to be possible in divided societies, and where the explanation of this phenomenon was the application of the principles of grand coalition, autonomy, proportionality, and minority veto – the four defining characteristics of consociational democracy – all of which clearly contrast with majoritarian principles.

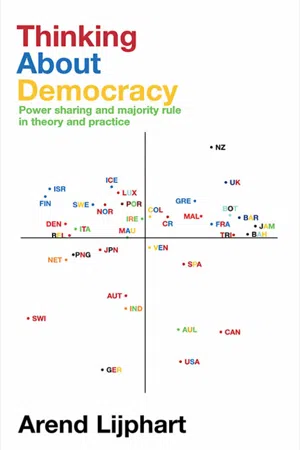

In my 1984 book Democracies and 1999 Patterns of Democracy, I reversed this procedure. I began by enumerating the major characteristics of majoritarian democracy, and subsequently defined each trait of nonmajoritarian democracy as a contrast with the corresponding majoritarian trait.2 I intentionally labeled this non-majoritarian model ‘‘consensus democracy’’ in order not to confuse it with the similar but not identical concept of consociational democracy. The first five majoritarian characteristics are concentration of executive power in single-party majority cabinets, executive-legislative relationships in which the executive is dominant, two-party systems, majoritarian and disproportional electoral systems, and pluralist interest group systems with free-for-all competition among groups. The five contrasting consensus characteristics are executive power sharing in broad multiparty coalitions, executive-legislative balance of power, multiparty systems, proportional representation, and coordinated and ‘‘corporatist’’ interest group systems aimed at compromise and concertation.

These differences are formulated in terms of dichotomous contrasts between the majoritarian and consensus models, but they are all variables on which particular countries may be at either end of the continuum or anywhere in between. These five variables are closely correlated with each other; that is, if a particular country occupies a particular position on one continuum, it is likely to be in a similar position on the other four continua. The five variables can therefore be seen as a single dimension, which for brevity’s sake I have called the executives-parties dimension.

A second set of five interrelated variables forms a clearly separate dimension, which I have called the federal-unitary dimension because most of the differences on it are commonly associated with the contrast between federal and unitary government. The majoritarian (unitary) characteristics are unitary and centralized government, concentration of legislative power in a unicameral legislature, flexible constitutions that can be amended by simple majorities, systems in which legislatures have the final word on the constitutionality of their own legislation, and central banks that are dependent on the executive. The five contrasting consensus characteristics are federal and decentralized government, division of legislative power between two equally strong but differently constituted houses, rigid constitutions that can be amended only by super-majorities, systems in which laws are subject to a judicial review of their constitutionality by supreme or constitutional courts, and independent central banks.

An obvious difference between the consociational and consensus models is that the former is defined in terms of four and the latter in terms of ten characteristics. A second clear difference is that the four consociational principles are broader than the consensus traits that appear to be the most similar. For instance, a consociational grand coalition may take the form of a consensual, broadly representative, multiparty coalition cabinet, but it may also take various other forms, like informal advisory arrangements and alternating presidencies (which may be thought of as a sequential ‘‘grand coalition’’). Moreover, for consociational democracy it is the inclusion of all distinctive population groups rather than all parties that is important when these groups and the parties do not coincide. Federalism is merely one way of establishing group autonomy. The most important aspect of the consociational principle of proportionality is proportional representation (PR), but it also includes proportionality in legislative representation that can occur without formal PR, proportional appointment to the civil service, and proportional allocation of public funds. The minority veto is a broader concept than the mere requirement of extraordinary majorities to amend the constitution. On the other hand, the consensus model’s features of bicameralism, judicial review, and independent central banks are not part of the consociational model.

These two differences can be summarized as follows: Consociational and consensus democracy have a large area of overlap, but neither is completely encompassed by the other. This means that consociational democracy cannot be seen as a special form of consensus democracy or vice versa.

A third difference emerges from the discussion of the first two. Where consensus and consociational democracy differ, the former tends to emphasize formal-institutional devices whereas the latter relies to a larger extent on informal practices. Fourth, as already implied earlier, the characteristics of consensus democracy are defined in such a way that they can all be measured in precise quantitative terms – which is not possible for any of the four consociational characteristics.

Finally, although both consociational and consensus democracy are highly suitable forms of democracy for divided societies, consociationalism is the stronger medicine. For instance, while consensus democracy provides many incentives for broad power sharing, consociationalism requires it and prescribes that all significant groups be included in it. Similarly, consensus democracy facilitates but consociational democracy demands group autonomy. Hence for the most deeply divided societies, I recommend a consociational instead of merely a consensus system. At the same time, the differences between them do not entail any conflict, and they are perfectly compatible wi...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Part I: Introduction

- Part II: Consociational and Consensus Democracy

- Part III: Majority Rule

- Part IV: Presidential Versus Parliamentary Government

- Part V: Proportional Versus Majoritarian Election Systems

- Part VI: Conceptual Links to the Fields of Political Behavior, Foreign Policy, and Comparative Methodology

- Part VII: Conclusion

- Bibliography: The Complete Scholarly Writings of Arend Lijphart