eBook - ePub

Developmental Dyspraxia

Identification and Intervention: A Manual for Parents and Professionals

- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Developmental Dyspraxia

Identification and Intervention: A Manual for Parents and Professionals

About this book

First published in 2007. Research suggests that between five and ten per cent of all children are dyspraxic. There is much debate about the nature of this disorder and many undiagnosed youngsters are denied access to treatment programmes. In most areas specialist provision is a scarce resource and support, when available, is delivered through parents and teachers. This second edition of Madeleine Portwood's successful manual aims to give parents, teachers and health professionals the confidence to diagnose and assess dyspraxia. Most importantly. it offers them an intervention programme which will significantly improve the cognitive functioning of the dyspraxic child or teenager. Updated in light of the author's new and extensive research, the book provides the reader with: background information on the neurological basis of the condition; strategies for identification/diagnosis and assessment; proven programmes of intervention which can be monitored by anyone closely involved with the child; strategies to improve curricular attainments; remediation activities to develop perceptual and motor skills; programmes to develop self-esteem information about where to find help

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Developmental Dyspraxia by Madeleine Portwood in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Since the publication of my first manual in June 1996 a great deal of research has focused on external factors such as nutrition and the effect of the environment on the developing child. My own studies during the past two years provided access to a greater sample population of children and young adults and have clarified my thinking about the condition termed dyspraxia. This second edition encompasses much of the recent research evidence and its implications for parents and teachers.

I became interested in the subject in 1988 after attending a seminar to discuss the increasing numbers of research papers suggesting that a high proportion of youngsters with emotional and behavioural difficulties showed evidence of significant neurological immaturity.

I was employed then by Durham Local Education Authority as Specialist Senior Educational Psychologist for children with emotional and behavioural difficulties, and screened 107 youngsters aged between 9 and 16 in the county. All had been identified as having special educational needs and allocated day or residential provision for their extreme behavioural difficulties. In that sample, 82 (77 per cent) of the pupils showed symptoms of neurological immaturity.

Research suggests that between 5 and 10 per cent of the general population would expect to have similar immaturities but with this elevated figure of 77 per cent in the sample assessed, it would be reasonable to assume that this factor must be significant in the development of subsequent unacceptable behaviours.

Many of these pupils had experienced failure from an early age. Delayed language development, poor social skills and a lack of co-ordination had forced isolation within their peer group. Many had become the victims of more assertive pupils. For some of the youngsters there were additional problems in their home environment. Some had suffered extreme emotional and material deprivation, others had presented as extremely difficult youngsters from birth with parents resorting to respite care and/or medication to enable them to cope.

There are occasions when environmental factors form the sole basis for explanations about a child's behaviour. It is important to take a more detailed overview and explore factors within the child before reaching any conclusions.

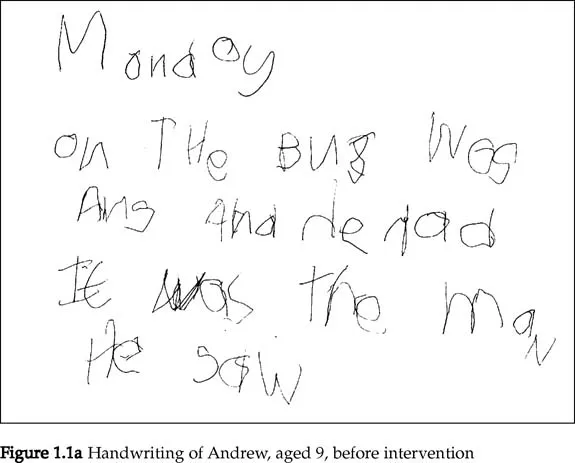

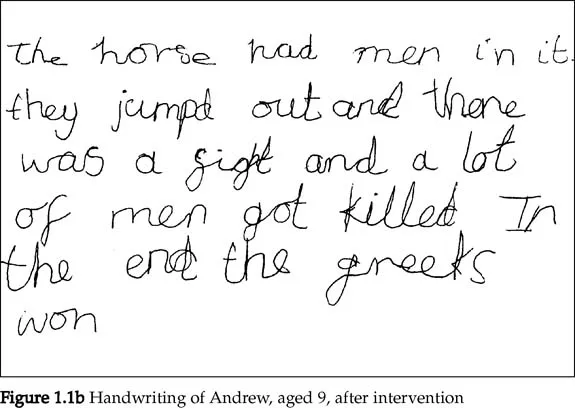

In my original sample of 107 pupils, 12 were selected from the identified 82 for intervention. Their intellectual ability was assessed using the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children — RS (WISC-RS) and found to be in the average range despite a number of very low scores in some of these sub-tests. In addition these youngsters had spelling ages of at least three years below their chronological age and their handwriting ranged from barely legible to illegible. In the sample, nine had reading ages, assessed using the Edwards Test, which were at or above their chronological age.

Members of the school staff agreed to supervise individual motor-skills programmes which were provided for each child and followed daily for 20 minutes. Progress was evident by the end of the first month, but within six months there was improvement, not only in language and handwriting skills (see Figure 1.1) but in concentration and behaviour. It was apparent that these youngsters had ‘failed’ in the educational system because of their inability to perform to expectation. Their frustration had led to displays of uncontrolled emotion which had resulted in significant behavioural difficulties. It seemed certain that, had the ‘problem’ been diagnosed at a much earlier stage, many of these children would not have been labelled as behaviourally difficult, and they would not have been placed in an educational environment away from their mainstream peers.

The ‘symptoms’ identified in the previous paragraph characterise the condition defined as dyspraxia. My confidence in stating this comes ten years later after being involved with more than 600 children and young adults with similar difficulties.

In 1990, after working extensively with youngsters who had been offered alternative educational provision, my next area of study was to consider approaches to identify and prepare intervention programmes for those within the mainstream sector experiencing similar difficulties, and probable candidates for such provision in the future. Pupils referred for psychological assessment usually exhibited recurring displays of unacceptable classroom behaviour, although a minority of the youngsters appeared to be extremely withdrawn. Most of the youngsters were aged between 8 and 11, with the sample heavily skewed to the older end because of the fear that ‘although we have managed to “contain” him here, he will never make it in secondary school.’ After identification, the youngsters were given access to a series of graded motor-skills activities. Programmes and methods of determining the children's access points are detailed later. Within the primary sector I was given access to data collected by other educational psychologists in Durham and this greatly increased the size of the sample.

The assessment techniques developed for use by teachers to identify dyspraxic youngsters in school were tested between 1988 and September 1993. I embarked then on a control study with children aged between 5 and 7, as research has shown that the earlier the diagnosis, the greater the impact of any intervention programme. This study was undertaken at an infants school in the county and included eight pupils aged between 5 years 3 months and 6 years 8 months. The results of the programme were extremely encouraging.

The research was then extended to older pupils as I believed it was important to develop access to programmes in secondary schools. My initial assumption was that, given the differences between the primary and secondary school environment and the age of the pupils, success would be the exception rather than the rule. I had made a total misjudgement: on the whole the pupils themselves were more committed to remediating their difficulties than the younger children.

This research was published in 1996 and attracted a great deal of media attention. I was approached by Sheilagh Matheson, the producer of the BBC2 programme Close Up North who was interested in the relationship between dyspraxia and juvenile delinquency. She arranged access to Deerbolt Young Offenders Institution in Barnard Castle and I screened 69 of the youngsters aged between 15 and 17. More than 50 per cent of the youngsters assessed showed varying degrees of dyspraxia.

The programme also followed a youngster who was 4 years of age and due to enter reception class. He had been identified by a speech therapist six months previously as a child who displayed the symptoms of developmental dyspraxia. His progress was filmed over a period of eight weeks to determine the success of the intervention programme. The extent of my research, which is from birth to adulthood, is outlined in later chapters.

As more research evidence becomes available the term dyspraxia becomes more complex.

2 Development of the brain and the significance of diet

Dyspraxia results when parts of the brain have failed to mature properly. To understand the complexities of the condition it is important to consider the early development and subsequent functioning of the brain.

Five weeks after conception cells within the developing embryo specialise to form the nervous system. As the brain develops, cells move, cells die, connections are made and broken as the brain assimilates information from sensory input. Eventually the brain develops into a network of 10 billion cells with 1 million billion connections. The brain adapts the body to the environment, through a process of natural selection reinforcing the connections between nerve cells which are most advantageous to the individual.

Esther Thelen, a developmental psychologist at the University of Indiana, has completed an extensive study of babies and produced strong evidence that selection plays an important role in the development of human behaviour. A month-old baby is able to fixate on a suspended object in its line of vision. At 2 months the baby is able to make anticipatory movements towards the object with a closed fist. At this age the child does not know how to co-ordinate movements. In Dr Thelen's study, motion sensors were attached to babies which tracked and recorded their movement in space. This movement was monitored to determine how skills are acquired. By the age of 6 months the child is able to reach and grasp appropriately.

Conventionally, it was believed that skills such as learning to reach are genetically programmed and the brain directs the body to perform certain activities. However, her research discovered that each baby has to solve for himself the sequence of instructions which will result in reaching towards the object. The baby has a range of movements and has to select from these the ones which work. He must locate the place in space to grasp the toy. The baby produces a large repertoire of random movements, making facial grimaces as well as flapping his arms and legs, while grasping at empty space. Occasionally, by chance, he will make contact with the toy. Over time, repeating this variety of movements, the repertoire is narrowed down to enable the action to produce the desired contact. The child is beginning to be able to exert some control over his environment. The next question must be: how does the brain produce this controlled behaviour?

Gerald Edelman, a biologist who won the Nobel Prize in 1972 for his theory that the immune system works by a process of natural selection, has suggested a possible explanation. The source of this information is his book Neural Darwinism. The Theory of Neuronal Group Selection (1989). His thoughts are extended in Bright Air, Brilliant Fire on the Matter of the Mind(1992).

There are over 200 types of cells in the human body and one of the most specialised is the nerve cell (neurone). It differs from other cells because of its electrical and chemical function and the means by which it is connected to other nerve cells.

The brain is richly supplied with these nerve cells which are interconnected via complex neural systems. There are two kinds of nervous system organisations, which are very different, even though both are made up of neurones.

- The brain stem and limbic system have evolved to understand the signals within the body. They respond to feelings such as hunger and anxiety and are connected to a variety of body organs, the endocrine system and the autonomic nervous system. These systems are responsible for regulating heart beat, respiration and digestion. They also determine the body's sleep cycle.

- The thalamo-cortical system which consists of the thalamus and the cortex acting together to receive signals external to the body. The cortex is adapted to receive signals from the sensors which respond to sight, touch, taste, smell, hearing and the body's awareness of its position in space.

Within these two systems the greatest area of interest is the cerebral cortex where much of the higher brain function takes place. Thoughts and actions are the result of signals travelling between nerve cells and, if the cortex is magnified, each region shows millions and millions of cells. Thousands of new cells are interconnected to produce a complex network. The cortex contains billions of specialised neurones and their function is to transfer signals from one part of the nervous system to another.

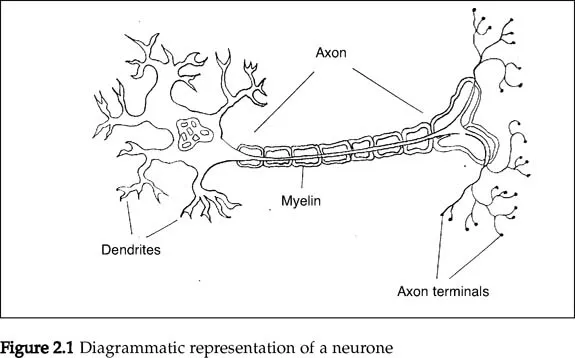

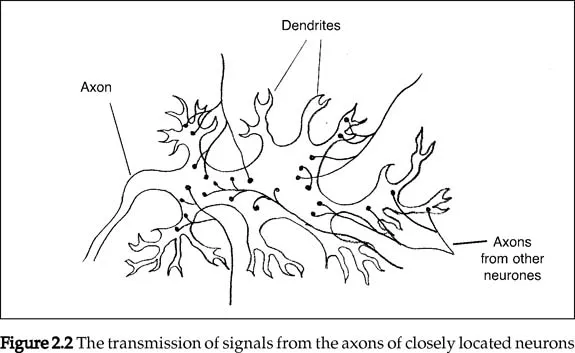

The neurone comprises a cell body, projecting from which are a number of short branches called dendrites (see Figure 2.1). The dendrites receive messages from other neurones and the message is transmitted through the axon, which is a tubular extension of the cell. Nerve impulses can travel only in one direction across the junctions (synapses) between neurones, so the axon of one neurone takes position close to the dendrites of another. A single neurone can receive messages through its dendrites from many other neurones which are transmitting via the axon (Figure 2.2).

The synapse is the point at which the message is transferred from one cell t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Full Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Forewords

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Chapter 1 Introduction

- Chapter 2 Development of the brain and the significance of diet

- Chapter 3 What is dyspraxia?

- Chapter 4 Observable characteristics

- Chapter 5 Research evidence

- Chapter 6 Behavioural problems: neurological? psychological?

- Chapter 7 Intervention in the ‘early years’

- Chapter 8 Intervention with primary and secondary age pupils

- Chapter 9 Adults with dyspraxia

- Chapter 10 Epilogue

- Appendices

- Bibliography

- Index