Chapter 1

Introduction and procurement fundamentals

Derek H.T.Walker, Justin Stark, Mario Arlt and Steve Rowlinson

Chapter introduction

This chapter discusses procurement fundamentals from a PM context that sets the scene for the rest of the book. We argue that delivering value is the main purpose of PM and that value is generated by PM teams for customers and stakeholders including organisations involved in the PM process. We assert that a sustainable procurement process provides a way that value is generated for all parties concerned because envisioned value generation is a strong motivator of the required level of commitment and enthusiasm necessary to generate win–win rather than win–lose outcomes.

At the heart of value generation is the issue of who participates in this process. This brings to the surface the primary make-or-buy decision that involves determining which parties are best prepared, suited and equipped to undertake specific parts of a project. That leads to determining how to best procure the required resources whether they be internally or externally sourced. While a portion of the project will be inevitably undertaken by those in the lead or PM role position (even if that contribution is solely to coordinate activities), much of the project work will be outsourced. This chapter will focus upon the procurement fundamentals of the outsourcing rationale. It is often assumed as a ‘given’ without looking at this decision from a value generation and maximisation point of view.

This chapter starts by discussing the concept of ‘value’ and moves on to question and discuss what an organisation actually is and how it can deliver value. The next section focuses upon the nature of outsourcing and its derivatives. That leads into the issue of transfer pricing and how value generation is treated in a global context because the trend towards global outsourcing has led to often complicated taxation and value recognition issues. Privatisation is also discussed in this chapter because many of the major projects being undertaken by the private sector have been shifted through government policy in all market economies from the public sector to the private sector or through a partnership of public and private enterprises.

The nature of value

Value is in the eye of the beholder. Because the appreciation of value is governed by perception, we must start with the stakeholders who have a need that requires satisfying or addressing. Chapter 3 will explore the stakeholder dimension of defining and contributing to value. Robert Johnston (2004) argues that customer delight lies at the top end of a continuum. This ranges from dissatisfaction where fitness for purpose is manifestly absent, through compliance with minimum expected delivery performance, to that higher level where exceptional value is delivered. Delight is, therefore, the result of (excellent) service that exceeds expectations. However, this may come at an excessive cost to either the provider or recipient. His study was based on gathering over 400 statements of excellent and poor service gathered from around 150 respondents. Participants’ phrases about excellent service provided by the respondents fell into four relationship-based categories:

- delivering the promise;

- providing a personal touch;

- going the extra mile and

- dealing well with problems and queries.

Characteristics of poor service were essentially the converse of excellence (Johnston, 2004: 132). The interesting part of this study, which related to customer service in general rather than procurement process in particular, was that while category one is transactional and satisfaction of the stated standard appears to suffice, the other three categories are about intangible and often poorly explicated standards. We could recognise value, therefore, as being not simply fitness for purpose at an agreed price in a timely manner but also as providing intangible deliverables for organisations that may include excellence in quality of relationships, leadership, learning, culture and values, reputation and trust. It is not easy to identify and prepare PM processes that have well-operationalised and developed measures to monitor and ensure effective delivery. However, Nogeste (2004) and Nogeste and Walker (2005) identify how this can be achieved. This aspect will be discussed later in more detail in Chapter 6. The point made here is that value is an amalgam of the ‘iron triangle’ of performance measures of time, cost and quality together with expectations and anticipated delivery of ‘softer’ often unstated needs. Traditional project delivery procurement systems may be adequate in defining tangible and defined outputs but they fall short in facilitating delivery of expected intangible and unstated outcomes. This brings in issues of expectations management as a valid aspect of project procurement processes. The extent to which these intangible outcomes are delivered is often associated with the level of customer delight and value.

Returning to the more tangible and defined elements of value, another way of viewing value for money is receiving a project or product at a reasonable price that reflects input costs and is delivered within a reasonable timeframe at the specified quality level. This concept of value relates to ethical and governance issues. Taking an extreme example, slave labour or using stolen materials could arguably deliver lower costs; however, this would be unfair and unethical. Issues relating to ethics and governance will be discussed in more detail in Chapter 4. Similarly, a process that ensures open and transparent availability of cost and scheduling information, for example, can provide a set of project governance property arrangements to satisfy fairness criteria. Thus, provisions for demonstrating value can be structured into procurement processes. Further, as will be discussed in Chapter 8, procurement options can be designed to facilitate innovation and/or organisational learning. Similarly, a focus on talent, both from the point of view of attracting talented project team members and developing capacity in teams and stakeholders, can also be designed into procurement choices. This is discussed in more detail in Chapter 10.

Another way of looking at value is to ensure that delivered projects meet strategic needs of stakeholders. An inexpensively delivered factory (strategically) located in the wrong place will not deliver competitive advantage and hence will have sub-optimal or negative value. For many change management or product development projects, making the correct strategic choice is part of the project procurement process – especially as many of these projects use organisation-internal markets to resource these projects. This aspect will be further discussed in Chapter 5.

New technology, particularly an e-business and information and communication technology (ICT) infrastructure, can offer new ways of configuring procurement options and can impact new processes and ways of both procuring and delivering projects. These innovative approaches can enhance value to be delivered and this aspect is presented in more detail in Chapter 7.

Much of the focus of this book, particularly Chapter 2, lies with exploring the range of procurement options open to deliver value in projects by matching these against the context of the project’s need to be satisfied. The cultural dimension of both generating trust and commitment from all parties is explored in Chapter 9, and this is particularly important for relationship-based procurement options (Walker, 2003).

The nature of projects and project management

The PMBOK provides a useful definition of a project and project management. A project is defined ‘as a temporary endeavour undertaken to create a unique product, service or result’ (PMI, 2004: 5). Project management is said to be the application of knowledge, skills, tools and techniques to project activities to meet project requirements. Four main processes are listed: identifying requirements; establishing clear and achievable objectives; balancing competing demands for quality, scope, time and cost; and adapting the specifications, plans and approach to the different concerns and expectations of various stakeholders (PMI, 2004: 8).

Turner and Müller (2003) remind us that a project uses a temporary organisation to deliver its outcome and that there are transaction costs inherent in a project that do not appear in established ongoing production organisations. They also stress that much of the project manager’s role is motivating team members, stakeholders and shaping agendas. They describe features of a project as follows (Turner and Müller, 2003: 2):

The project aim is to deliver beneficial change. Features include uniqueness, novelty and transience. Pressures typically encountered are in managing to cope with uncertainty, integration and transience. Processes need to be flexible, goal oriented and staged.

Value in terms of projects is apparently more complex an issue than standard factory production of ‘widgets’ because the management and leadership intensity involves mobilising transient groups of people brought together for a limited time to work on specific projects; people within these groups often exit part way through the realisation of these projects for one reason or another. That is why this book includes aspects of stakeholder identification and management (Chapter 3), organisational learning and knowledge management (KM) (Chapter 8), talent management (Chapter 10) and cultural dimensions (Chapter 9) that make establishing an optimal framework for delivering value so important. As the collection of government reports reviewed and commented upon by Murray and Langford (2003) clearly indicate, the procurement systems traditionally used in the UK construction industry fail to address the complex reality of how projects can best deliver the more holistic concept of value noted earlier in this chapter.

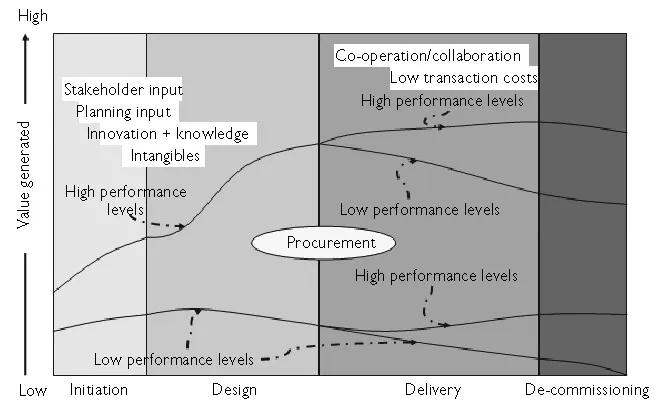

The phases of a project need to be considered so that optimum value is delivered because a project often takes a long time (many years) to deliver. A typical project can be seen to comprise of four principal often overlapping phases. These are illustrated in Figure 1.1.

At the initiation phase the project needs are identified, clarified and prioritised along with expected benefits, the strategic impetus for the project and developing and challenging the business case for the project. This is where stakeholder input can provide significant project potential value. The appropriate involvement of stakeholders and the management of this process are discussed in Chapter 3 in more depth. The need for identifying stakeholder potential impact can be of crucial importance and add value by identifying often hidden opportunities for planning input and knowledge and can unearth hidden risks and threats (Bourne and Walker, 2005a,b). Also, intangible value and benefits can be identified, analysed and linked to the tangible project deliverables (Nogeste and Walker, 2005). The design phase involves matching needs with proposals to deliver the required value to meet the identified needs. Stakeholder involvement, particularly in respect of prioritising needs and using value engineering techniques to optimise value (e.g. see Green, 1999), can deliver unexpected value. The design phase is usually followed by a process where the successfully selected project team is mobilised and resources procured to deliver the project. This is where sub-optimal procurement choices can have a profound impact upon project delivery value. The final phase noted above is de-commissioning and often a different set of additional stakeholders may be involved at this stage.

Figure 1.1 Project phases and performance.

Figure 1.1 illustrates two trajectories of project value generation throughout the project phases. At the initiation and design stages stakeholder input (including not only supply chain stakeholders but project end-users and others affected by the project’s existence) can provide critical definition and perceptions of value that may shape the evolving design details. High-level performance at this leading edge of the project time span is indicated by identification of misunderstandings of value perceptions at as early a stage as possible. These can include fully understanding the true needs driving the feasibility of the project, contextual knowledge and matters relating to planning and logistics. Without this kind of input from stakeholders, it is common for project designs to start sub-optimally with high expense and rework being required to remedy this if discovered later. Worse still, this input may be realised too late to effectively incorporate ideas that could optimally realise project value. This is why the chosen procurement process can have such a significant impact upon the stage before committing the project to detailed design and tender. As illustrated above, the gap between poor and good performance at this stage can be significant.

The second part of the trajectories illustrated in Figure 1.1 relates to the delivery phase spilling over to de-commissioning. The point made here is that even if a poorly initiated and designed project has a top-level project team carrying out the project, it is unlikely to yield as much value as a mediocre or poor project team delivering a project where there was high performance initiation and design established. For example, Barthélemy (2001) identified a proportion of the hidden costs associated with outsourcing contracts, and their management and maintenance, which include:

- searching for and identification of a suitable vendor;

- transitioning services to the external service provider;

- managing the day-to-day contract and its service deliverables and

- the effort required once the outsourcing contract agreement has been completed or terminated.

Figure 1.1 clearly demonstrates that the value contribution lies not only in the way that stakeholders and project team initiators behave and contribute, but also in the timing of their contribution. It shows how the procurement phase, which often spans the design and delivery phases, is pivotal in generating project value.

Procurement choices should be geared towards maximising value. This involves not only considering which type of contract to use but how to engage stakeholders, how to link business strategy to select the project initially, how to define value both in its more tangible and easily explicated form, and the hidden tacit aspirations of those who are meant to benefit from the project. Procurement choices should be about balancing demands and responsibilities; protecting reputations of those involved in the project against using unethical practices; encouraging innovation, best practice and knowledge transfer where it can reap value; developing project governance and reporting criteria that highlight, protect and generate value; and they should aim to attract the level of talent that can deliver stakeholder delight. Clearly, this vision of procurement positions itself far from the traditional lowest-cost strategy. It requires a more intelligent treatment of how best to facilitate the project to generate sustainable value. If the word ‘value’ appears overused in this chapter it is because it has been largely absent from ...