- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Coastal Systems

About this book

The coast represents the crossroads between the oceans, land and atmosphere, and all three contribute to the physical and ecological evolution of coastlines. Coasts are dynamic systems, with identifiable inputs and outputs of energy and material. Changes to input force coasts to respond, often in dramatic ways as attested by the impacts of the Indian Ocean tsunami in 2004, the landfall of Hurricane Katrina along the Gulf Coast of the USA in 2005, and the steady rise of global warming driven sea-level. More than half the world's human population lives at the coast, and here people often come into conflict with natural coastal processes. Research continues to unravel the relationship between coastal processes and society, so that we may better appreciate, understand, manage and live safely within this unique global environment.

Coastal Systems offers a concise introduction to the processes, landforms, ecosystems and management of this important global environment. New to the second edition is a greater emphasis on the role of high-energy events, such as storms and tsunamis, which have manifested themselves with catastrophic effects in recent years. There is also a new concluding chapter, and updated guides to the ever-growing coastal literature. Each chapter is illustrated and furnished with topical case studies from around the world. Introductory chapters establish the importance of coasts, and explain how they are studied within a systems framework. Subsequent chapters explore the role of waves, tides, rivers and sea-level change in coastal evolution.

Students will benefit from summary points, themed boxes, engaging discussion questions and new graded annotated guides to further reading at the end of each chapter. Additionally, a comprehensive glossary of technical terms and an extensive bibliography are provided. The book is highly illustrated with diagrams and original plates. The comprehensive balance of illustrations and academic thought provides a well balanced view between the role of coastal catastrophes and gradual processes, also examining the impact humans and society have and continue to have on the coastal environment.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 Coastal systems: definitions, energy and classification

- the definition of the coast from scientific, planning and management standpoints

- the sources of energy that drive coastal processes

- the architecture and working of coastal systems, introducing concepts of equilibrium and feedbacks

- an introduction to coastal classifications, with an emphasis on broad-scale geological and tectonic controls

- a discussion of the complexities of terminology used in studying coastal systems

1.1 Introduction

1.1.1 Defining the coast

Management Box 1.1

Definitions of the coastal zone for planning and management

- ‘the coastal waters and the adjacent shorelands strongly influenced by each other, and includes islands, transitional and intertidal areas, salt marshes, wetlands and beaches. The zone extends inland from the shorelines only to the extent necessary to control shorelands, the uses of which have a direct and significant impact on the coastal waters’ (United States Federal Coastal Zone Management Act)

- ‘as far inland and as far seaward as necessary to achieve the Coastal Policy objectives, with a primary focus on the land-sea interface’ (Australian Commonwealth Coastal Policy)

- ‘definitions may vary from area to area and from issue to issue, and that a pragmatic approach must therefore be taken’ (United Kingdom Government Environment Committee)

- ‘the special area, endowed with special characteristics, of which the boundaries are often determined by the special problems to be tackled’ (World Bank Environment Department).

1.1.2 Coastal energy sources

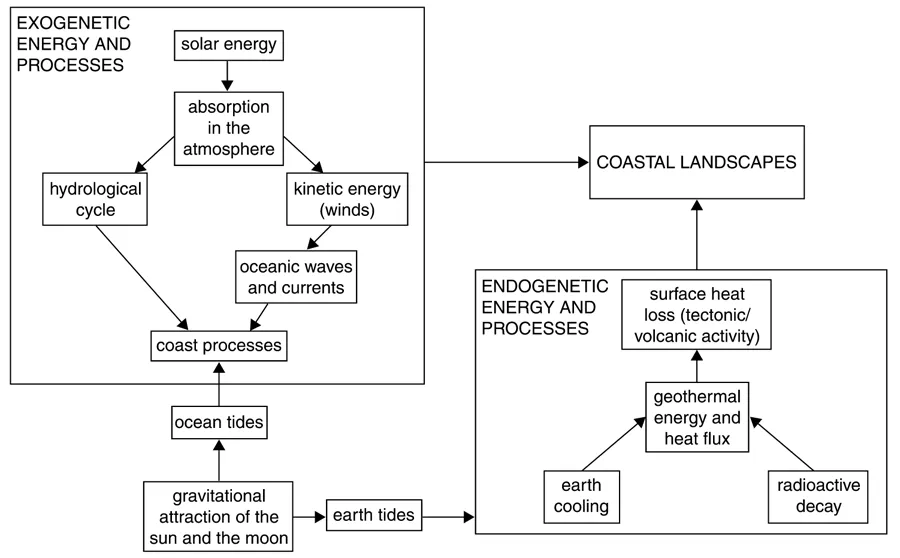

- The first category of processes is known as the endogenetic processes, so-called because their origin is from within the earth. Endogenetic processes are driven by geothermal energy which emanates from the earth’s interior as a product of the general cooling of the earth from its originally hot state, and from radioactive material, which produces heat when it decays. The flux of geothermal energy from the earth’s interior to the surface is responsible for driving continental drift and is the energy source in the plate tectonics theory. Its influence on the earth’s surface, and the coast is no exception, is to generally raise relief, which is to generally elevate the land.

- The second category of processes is known as exogenetic processes, which are those processes that operate at the earth’s surface. These processes are driven by solar energy. Solar radiation heats the earth’s surface which creates wind, which in turn creates waves. It also drives the hydrological cycle, which is a major cycle in the evolution of all landscapes, and describes the transfer of water between natural stores, such as the ocean. It is in the transfer of this water that rain falls and rivers flow, producing important coastal environments, such as estuaries and deltas. The general effect of exogenetic processes is to erode the land, such as erosion by wind, waves and running water, and so these processes generally reduce relief (however, sand dunes are an exception to this rule, being built up by exogenetic processes).

1.2 Coastal systems

1.2.1 System approaches

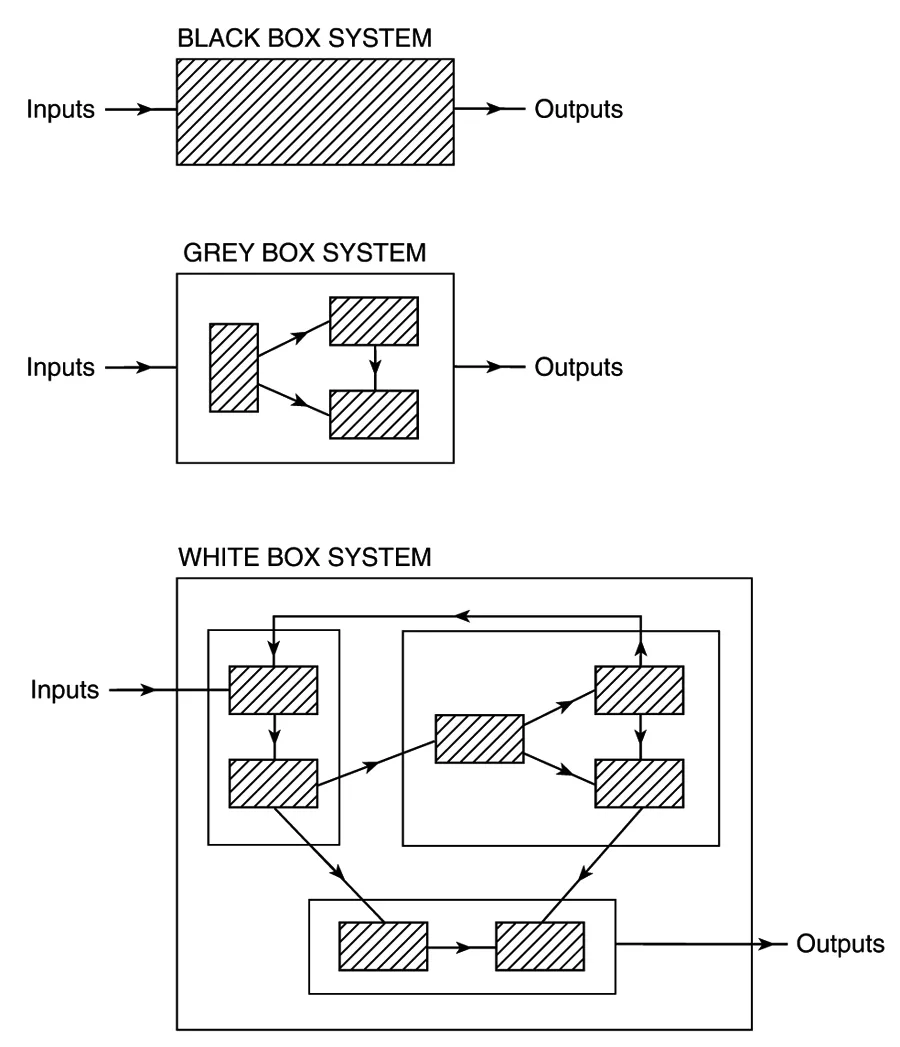

- Morphological systems– this approach describes systems not in terms of the dynamic relationships between the components, but simply refers to the morphological expression of the relationships. For example, the slope angle of a coastal cliff may be related to rock type, rock structure, cliff height, and so on.

- Cascading systems—this type of system explicitly refers to the flow or cascade of energy and matter. This is well exemplified by the movement of sediment through the coastal system, perhaps sourced from an eroding cliff, supplied to a beach, and then subsequently blown into coastal sand dunes.

- Process-response systems—this combines both morphological and cascading systems approaches, stating that morphology is a product of the processes operating in the system. These processes are themselves driven by energy and matter, and this is perhaps the most meaningful way to deal with coastal systems. A good example is the retreat of coastal cliffs through erosion by waves. Very simply, if wave-energy increases, erosion processes will often be more effective and the cliff retreats faster. It is very clear from this example, that the operation of a process stimulates a morphological response.

- Ecosystems—this approach refers to the interaction of plants and animals with the physical environment, and is very important in coastal studies. For example, grasses growing on sand dunes enhance the deposition of wind-blown sand, which in turn builds up the dunes, creating further favourable habitats for the dune biological community, and indeed may lead to habitat succession.

1.2.2 The concept of equilibrium

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- List of plates

- List of figures

- List of tables

- List of boxes

- Author’s preface to the first edition

- Author’s preface to the second edition

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Coastal systems: definitions, energy and classification

- Chapter 2 Wave-dominated coastal systems

- Chapter 3 Tidally-dominated coastal systems

- Chapter 4 River-dominated coastal systems

- Chapter 5 Sea level and the changing land-sea interface

- Chapter 6 Coastal management issues

- Conclusion

- Glossary

- Further reading

- Bibliography

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app