Introduction

On 2 November 2004, a 26-year-old Dutch national of Moroccan descent fired a gun six times at, and slit the throat of, Dutch film-maker Theo van Gogh, killing him on the spot. On 22 December 2001, a Jamaican-British man boarded a plane in Paris bound for Miami. During the flight he attempted to ignite an explosive hidden in his shoe with the intention of bringing the plane crashing down to earth. In August 2001, a 34-year-old French national of Moroccan descent was arrested by US federal agents because while taking flying lessons he was neither interested in learning landings or takeoffs. His arrest was later brought in connection with the 9/11 attacks. These three cases are instances of Muslim extremist terrorism or attempts thereof committed by European nationals. This chapter tries to offer an answer to the question of how the European Union can deal with these “home-grown” terrorists and stifle their radicalization and recruitment. Due to the nature of the threat, European states cannot address the root causes of terrorism and solve terrorism altogether, yet instead the European Union needs to develop an effective strategy targeting radicalization and recruitment.

Anti-systemic terrorism

In their study Political Terrorism, Alex Schmidt and Berto Jongman identified 109 different definitions of terrorism.2 In general, terrorism can be defined as the intentional use of, or threat to use, violence against civilians and civilian targets, in order to attain political aims. The EU uses the following definition of terrorism.

Terrorist acts are those that:

A serious problem is that this definition says little about the nature of the present threat. As a consequence its policy implications are hard to define. Traditionally, terrorists used well-known techniques such as hostage taking, murder, blackmail and terror aimed at specific segments of the population to reach specific, limited political objectives such as the release of prisoners. Their operations could be deadly, but did not affect the lives of many citizens. Nonetheless, a few well armed terrorists could seriously disrupt public order, as violence against citizens results in fear and chaos. Liberal democracies have always been extremely vulnerable to terrorism. The threat of the use of weapons of mass destruction and disruption is however a relatively recent phenomenon.

Since the targets are civilians, terrorism is distinguished from other types of political violence, such as guerrilla operations. The latter is defined as a form of warfare against a state by which the strategically weaker side assumes the tactical offensive in selected forms, times and places. The 9/11 attacks carried out by Osama bin Laden’s Al-Qaeda network blurred the traditional distinction between terrorism and war. War is usually associated with combating state actors which pose a threat to international peace and security; terrorism is usually associated with deadly, but small-scale actions and limited objectives.

However, the new threat cannot be considered a tactical or local challenge, requiring cooperation between the national intelligence services and the police. The new threat is strategic and international in nature, which requires international cooperation among intelligence services, armed forces and the traditional law enforcement authorities. Combating terrorists could involve interventions in failed and weak states, especially black holes, those areas used by terrorists as sanctuaries. Here terrorists could use small armies to protect their interests. For example in Afghanistan, bin Laden used the 5,000-strong multinational Arabic “055 Brigade” to protect his training camps, other bases and to keep elements of the Taliban in check. Terrorist organizations could possess the military capabilities of small states and turn non-military means, such as airliners, into weapons of mass destruction to achieve strategic objectives.4

The new threat is sometimes defined as catastrophic terrorism5 because it aims to kill people on a large scale. This, however, does not explain the specific nature of the threat. The attacks of 9/11 were directed at outstanding symbols of Western civilization; bin Laden had often spoken of targeting the “Zionist-Crusader Alliance” and of dealing blows to Americans and Jews.

This kind of terrorism is of a cultural and religious nature and aimed at removing alien influences from the Islamic world. Therefore some authors name the new threat cultural or religious terrorism, which is not an accurate description either.6 Under such a definition, 9/11 and the destruction of two giant Buddha statutes of Bamiyan, Afghanistan by the Taliban in February 2001 fall in the same category. What really distinguishes the events of 9/11 from other terrorist acts is that the terrorists try to change the international system through mass destruction. A better term therefore is anti-systemic terror, defined as the unconventional, but worldwide and large-scale use by (state-sponsored) non-state actors against civilian and government targets, with the aim to change the international system.

Three layers

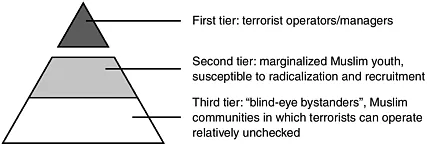

Stopping terrorists implies looking for a limited number of people. Although the numbers are small, the manner in which terrorist organizations organize and manifest themselves dictates substantial policy implications. Besides being spread out internationally, their recruitment activities and operations take place within the fabric of society instead of isolated from it. The operations in modern societies of terrorist organizations such as Al-Qaeda are enabled by three groups, or tiers, which can be represented in a pyramid structure (Figure 1.1).

• The first tier is formed by the “operators/managers”; these individuals often have experience in fighting as a jihadist or mujahideen, are generally well-educated and are part of the “staff” or management of the terrorist group.

• Disenfranchised, marginalized young Muslims make up the second tier; the members of this group are, due to political, social and/or socio-ethnic alienation, in search of an identity and are willing to assert themselves in the outside world. This pool of individuals is susceptible to radicalization because of its willingness to act.

• Finally, there are the “blind-eye bystanders”, the third tier. This group neither supports nor opposes the operations of terrorists and it is in these communities that disenfranchised youth live and where the operators/managers immerse themselves.7 This can be conceptualized as similar to Mao Zedong’s view that guerrilla soldiers must operate as “fish in the sea”, whereby the latter consists of a particular group of the population which offers tacit support, although short of being complicit to the guerrillas’ activities.

Because the two bottom tiers are also present within European countries, they are suitable recruitment and radicalization grounds for Islamic extremists.

Causes of terrorism

Anti-systemic terror is associated with Osama bin Laden’s Al-Qaeda network. His goal is to unite all Muslims and to establish a government which follows in

the footsteps of the Caliphs, the ancient religious rulers. The only way to do so is by the use of force. Muslim governments need to be overthrown because they are corrupt and are influenced by the “Zionist-Crusader Alliance”; an alliance of Jews and Christians, embodied by Israel and the United States and supported by Western liberal democracies in general. In bin Laden’s view, this unholy alliance has occupied the land of Islam’s holy sites (Mecca, Medina and Jerusalem) and tries to crush Islam altogether. To end this influence, the destruction of Israel and the United States is a prerequisite for reform in Muslim societies. Consequently, in August 1996 bin Laden issued a “Declaration of War” against the United States. While in his March 1997 interview with CNN’s Peter Arnett, bin Laden said that he would only target US soldiers, he hardened his line in his fatwah issued in February 1998, when he called for attacks on Americans wherever they can be found.

A paradigm supported by history

A brief overview of several historical elements upon which bin Laden justifies Al-Qaeda’s actions against the “Zionist-Crusader Alliance” yields insights into the mind of the Muslim extremist and is helpful in unearthing the motivating factors for Al-Qaeda’s operations.

The 1998 fatwa, the “Declaration of the World Islamic Front for Jihad against the Jews and the Crusaders”, described the US presence in the Middle East as a catastrophe that had humiliating and debilitating effects on Muslims. Bin Laden wrote, “Since God laid down the Arabian peninsula, created its desert, and surrounded it with its seas, no calamity has ever befallen it like these Crusader hosts that have spread in it like locusts, crowing its soil, eating its fruits, and destroying its verdure.”

A Western power has never occupied the Hijaz (the region of Islam’s holy places) in Muslim history. Traditionally, non-Muslims are not permitted to enter Mecca and Medina based on the Prophet’s deathbed statement, “Let there not be two religions in Arabia”. Bin Laden cites as an example the Crusader, Reynald of Chatillon in 1182, who attacked Muslim caravans in the Hijaz, including those of pilgrims to Mecca. His actions were perceived as a “provocation” and a “challenge directed against Islam’s holy places”. Historians of the Crusades state that Reynald’s motive was primarily economic—desire for loot. However, bin Laden describes this as a campaign of provocation, a challenge directed against Islam’s holy places. More than eight hundred years later, bin Laden applies the same principle and interprets the US presence as an equal provocation requiring retribution. Bin Laden conveniently ignores the fact that there is no Western presence in the Hijaz region of Saudi Arabia.

A key historical event in the development of the global jihad movement is one mentioned by bin Laden himself. In a taped message of 7 October 2001 bin Laden spoke about “the tragedy of Andalusia (Al-Andalus)”, which refers to the conquering in 1492 of the Muslim Kingdom of Granada by the Catholic monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella. It was a central moment in the Islamic caliphate’s quest for political and military power; Muslim expansion was not just checked, it was reversed. Moorish armies from North Africa had conquered the Iberian Peninsula in the eighth century and transformed the region into an integral part of the Muslim ummah, or community of believers. The “humiliation” has never been forgotten in parts of the Arab world, especially not by bin Laden and his followers.

Another key moment was the Sykes-Picot agreement (1915), which planned the division of the Arab provinces of the Ottoman Empire between the British and the French after the Second World War. Bin Laden’s prime goal is said to be the restoration of the Islamic caliphate, and the Sykes-Picot agreement signalled, to bin Laden, the collapse of Muslim political and military power. The end of the Second World War meant “the destruction of the old order which, for better or for worse, had prevailed for four centuries or more in the Middle East”. Throughout all these events bin Laden uses the historical term “crusaders” to describe the West and base that as a platform for war. Bin Laden however ignores that the Ottoman Empire was not a strict religious one and did not impose religion on all its subjects.

Other lesser or unknown groups inspired by Al-Qaeda might have similar perceptions as well. In general, Muslim extremism considers the war against the West a clash of civilizations. They hate everything that represents “decadent” Western civilization: commerce, most notably its banking system, sexual freedom, artistic freedom, secularism, democracy, religious tolerance, scientific pursuits and pluralism. They reject everything that makes Western civilization ...