![]()

1 Introduction

This Treason doth want an apt name.

Edward Coke, Chief Justice of Common Pleas Regarding the Gunpowder

Plot(1605)

Introduction

The President of the US looked visibly haggard on the eve of the fifth anniversary of the 9/11 attacks. George W. Bush's speeches in the immediate aftermath of the horrendous acts that claimed the lives of nearly 3,000 people were noted for their defiance. The self-assured man, enjoying an unprecedented popular support—nearly 90 per cent by some opinion polls—promised the country a quick resolution of the problem of terrorism. His swaggering speeches were peppered with such phrases as "rooting out" terrorism and "hunting down" those who were responsible for such a reprehensible crime. He boldly promised a nation hungry for revenge to deliver Osama bin Laden, the leader of al-Qaeda, "dead or alive." In a most grandiose scheme, the US counter-terrorism efforts were quickly dubbed as the "global war on terror." In an effort to eradicate the scourge of terrorism from the face of the earth, the Bush administration opened a two-front war in Afghanistan and in Iraq. The emergent Bush Doctrine put the entire world on notice: "You are either with us or against us." Any nation that would harbor terrorists or give aid and comfort would be held directly responsible for the actions of these groups. And if any foreign government was found supporting a terrorist group that targeted the US, its allies, or its global interests, it could expect unilateral actions by the US military disregarding any question of international legitimacy of such actions. According to the Bush Doctrine, the security of the US must override all other concerns and diplomatic niceties. The President, in his first speech immediately after the attacks, by drawing copiously from Christian imageries, declared America's fight against terrorism as the modern-day "Crusade."

Five years later, at the time of writing this book, with bin Laden still at large, the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan grinding on, and fresh attacks by the al-Qaeda still looming large in the mind of every American, President Bush appeared much more circumspect as he talked about a long, hard, ideological combat. The tone of his speech left no doubt in the minds of many that he was warning the nation of a generation-long struggle.

With the spectacular attacks, the trickle of literature on terrorism turned into a torrent. The need to know more about the people who would commit such an atrocity from a stunned populace was nearly insatiable. Not only was the general public hungry for information, but also various government agencies started contacting the experts in the field. Some of the best academic institutions quickly initiated new curricula on terrorism.1 In keeping with this exploding demand, the number of studies on terrorism has registered an exponential growth. As the discourse on terrorism grew, so did the need to put this burgeoning literature within a consistent theoretical perspective.

It is interesting to note that the Anglo-American scholarship was not interested in studying social conflicts. In 1964, facing an analogous situation of rising mass violence, Harry Eckstein, a prominent political scientist, lamented: "When today's social science has become intellectual history, one question will certainly be asked about it: why did social science, which had produced so many studies on so many subjects, produce so few on violent political disorder?"2

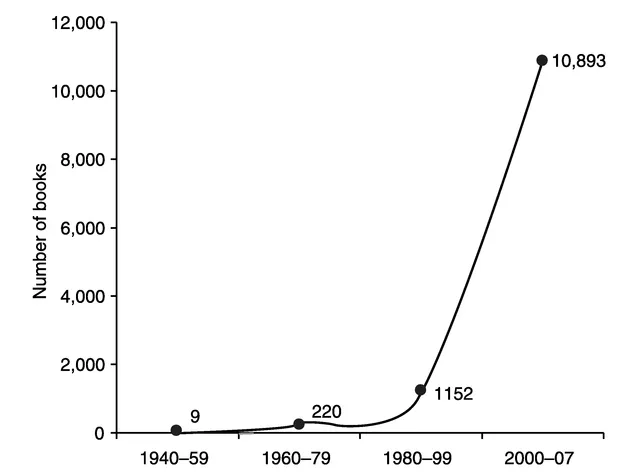

Although the attacks of 9/11 shook the country to its core, terrorism had been on the radarscope of the experts for decades prior to that fateful day. The rising concern over the capability of a relatively small group of non-state actors to inflict pain on a large segment of the population has been amply reflected in the number of books and articles that started coming out after 1940. A search in the University of California systems library catalog, MELVYL, shows the number of published books with the term "terrorism" in the title. I have presented the information in Figure 1.1, which amply demonstrates the exponential increase in the importance placed by the academic community on the study of terrorism.3 The number of books with terrorism in their title published in the six and a half years since 2000 was more than ten times the total number of publications for the past six decades.

This overwhelming addition to our knowledge poses the challenge of putting this vast literature in a conceptual framework. After providing a new approach to understanding human motivation in organized societies, this book is concerned about understanding the forces that shape the life cycle of violent political movements. How are these movements born? How and when do they grow rapidly? Under what conditions do some of these politically motivated groups lose their ideological bearing and become criminal in their orientation? When do they face defeat, disintegration, and political death?

In order to address these questions I will begin by taking stock of the existing literature on the theories of mass movements and terrorism. This burgeoning literature is the product of many scholars from many academic disciplines, journalists, policy analysts, and former intelligence officers, among others. Each group of authors follows its own set of objectives. While the academics tend to theorize about human behavior and analyze the long-term trends, the motivations of the journalists, policy-makers, and former intelligence officers are more immediate. In the second chapter, I have attempted to provide an analytical scheme with which to classify this burgeoning literature.

Figure 1.1 Published books with "terrorism" in the title.

Despite the impressive number of books and articles, the literature leaves a significant gap in providing us with a consistent theoretical structure for understanding the motivations for terrorism. This inadequacy stems from the poverty in the Western epistemological tradition, which does not allow us to completely grasp the motivations behind collective actions. Hence, in this book, by drawing from various fields, particularly by expanding the rational-choice arguments to include the findings of social psychology, I propose a new set of postulates for analyzing the motivations of the terrorists and their organizations.4 In Chapter 3, by combining insights from various branches of social sciences and social psychology, I posit my own hypotheses regarding motivation of individual members for joining a dissident group. I argue that economic theories, which equate human rationality with striving to maximize self-utility, miss another important motivational factor: the desire to further the welfare of the group in which we claim our membership. The desire to belong, which membership in a group offers, is just as strong and is inextricably intertwined with our self-love. Since terrorism is inherently an altruistic act, at least in the mind of the participant, we cannot fully comprehend it without the help of group motivation, the principal preoccupation of social psychology. Therefore, without properly understanding the motivations behind acts of altruism, we cannot differentiate between politically motivated violent actions from ordinary criminal enterprise.

By extending the factors of individual motivations to the group, therefore, Chapter 4 explains the dynamics of mass political movements. The evolution of a movement is deeply influenced by the responses of the target government. In this chapter I develop a theoretical perspective on the dynamic interactions with the society at large that shape the life cycle of a terrorist organization.

Based on this theoretical perspective, the next four chapters analyze the birth, growth, transformation, and demise of violent political movements. Although I draw upon examples of many dissident groups around the world, in my explanation I specifically concentrate on four political movements: Hamas, al-Qaeda, Irish Republican Army (IRA), and Naxalites. These four disparate groups were chosen for specific methodological reasons. They represent the diversity of ideology, chronology, and their relative positions on their particular life cycle. Let me explain.

If we look at the world of violent political movements, we can see that these four groups are organized around three, often overlapping, ideologies: nationalism, religious fundamentalism, and Communism. The forces that create nationalistic identity with which a segment of the population defines itself separately from the rest of the society often follow the contours of religious and/or economic class divisions. In the post-colonial world subnational separatism is inevitably associated with a feeling of deep exploitation by the majority of the minority population. A deep sense of injustice, the inspiration for many of these movements, stems from differential rates of economic growth, lack of political opportunities for specific groups, or the presence of oil and other natural resources to which the indigenous population feels a certain sense of entitlement. From Biafra to Bangladesh, from Croatia to East Timor, these separatist movements have often caused bloody civil wars, where two regular armies or organized militias have waged bloody warfare. Although many of these conflicts are labeled as "religious," "nationalistic" or "class warfare," these three seemingly distinct ideologies are often impossible to completely distinguish from each other.

If we look at our selected groups, we can see that they represent the entire ideological spectrum. While Hamas and the IRA are primarily nationalistic, al-Qaeda's goals are millenarian in nature. Hamas is fighting to establish a Palestinian state along the ideals of Sunni Islam, whereas the IRA, at least in the earliest periods of its history, was waging a war to unify the entire island of Ireland under a Catholic rule.5 In contrast, al-Qaeda is not aiming at establishing a single state, but wants to create an Islamic Caliphate stretching from Spain to Indonesia. The Naxalites, an insurgency group in India, in contrast, aim at establishing a Communist regime according to the ideals of China's erstwhile Communist leader, Mao Zedong. Yet the Naxalites in India, for instance, are flourishing only in the tribal regions where ethnic divisions are deep and abiding. Similarly, the IRA, a primarily nationalistic group based on Catholic identity, evolved to embrace socialist ideology. The Islamic millenarian movements, such as al-Qaeda, give expression to Islamic identity along with a strong economic egalitarian message. Moreover, in defining their fight against the West, they cannot often escape Arab/Islamic nationalistic aspirations.

These groups also offer a perfect diversity in terms of where they are in the life cycles of their movements. Thus, Hamas and al-Qaeda, barely a decade into their lives, have shown impressive strength in shaping the history of the twenty-first century. The IRA, the longest surviving dissident group in the world, after nearly 100 years of its existence is currently facing the prospect of a political death. Finally, the Naxalites in India, having been comprehensively defeated in the early 1970s, have come back with renewed vigor.

From time immemorial political extremists have been laying a trap for the state to overreact in a way that alienates those who were happy taking a moderate stance. The objectives of the terrorist groups are served when the government acts in a way that is perceived as immoral and uncalled for by a large section of the population. Although the motives of the terrorists are fairly clear on this, the state cannot give up its addiction to the failed policies of the past. In the final chapter I ask the question: why do we follow the same path of mutual destruction? Although terrorism has been a part of human society from its very inception, what has changed is the ability of a small group to inflict catastrophic amount of death and destruction. If the history of modern terrorism began with the invention of dynamite, in this age of advanced technology the risks of deaths of unimaginable magnitude is a real possibility. The question is: when we face attacks that would make the 9/11 incidents pale in comparison, will we collectively have the wisdom to separate myths from reality and move forward in a judicious manner? By drawing from areas of social psychology and cognitive sciences, I attempt to provide an answer to this puzzle and then address the question that is on everyone's mind: is the war against terrorism winnable?

Defining terrorism

In 1605, a plot was hatched by a group of provincial English Catholics to kill King James I of England, his family, and most of the Protestant aristocracy. The plotters tried to smuggle barrels of gunpowder into the vaults underneath Parliament House. The conspirators planned to blow it up during the State Opening, when the king was going to be in the House. The members of the "Gunpowder Plot" had also plotted to abduct the royal children, and incite a revolt in the Midlands. The enormity of the conspiracy left Edward Coke, the Chief Justice of Common Pleas, searching for an appropriate word to describe it. The "reign of terror" (la Terreur) following the French Revolution, which gave birth to the term "terrorism," would have to wait for almost two hundred years to be coined. Coke was at a loss to find a suitable sobriquet, which would adequately capture the revulsion, scorn, and disgust the hatched plot evoked in him. He expressed his bewilderment by stating: "This Treason doth want an apt name." President Bush would similarly look for an appropriate term to describe those who could plot mass murders on such a scale. He would use term such as "Islamic terrorists" or "Islamofascist" to express his indignation toward the radical Islamic groups that threatened his nation. Others have similarly tried in vain to coin terms, such as "suicide murderers" and "suicide terrorists," to capture their feelings toward the perpetrators of these attacks. In contrast, those who perpetrate these acts always see them as legitimate responses to their longstanding grievances, taken as the last resort in self-defense. In the Arab/Islamic world, the sympathizers of their ideological aims refer to them as "Shahid" or "martyrs." The chasm that separates the connotations of the two sets of terms are as wide as the view that separates the two worlds. In the blame game both sides of a terrorist attack see themselves as the victims.

Although the condemnatory epithet of "terrorism" has become a part of our everyday political lexicon, Rapoport points out that in the past many "terrorists" did not mind the label and, in fact, wore it as a badge of honor.6 Since the anti-colonial movements had a wide support base among their own people, their armed struggle to sow terror in the minds of their colonial lords was seen as legitimate; they proudly wore the name "terrorist." However, with time the anti-colonial organizations realized the need for "a new language to describe themselves, because the term terrorist had accumulated so many negative connotations that those who identified themselves as terrorists incurred enormous political liability."7 Lehi (acronym for Lohamei Herut Israel, "Fighters for the Freedom of Israel"), the Jewish extremist group operating in the British Mandate of Palestine, was perhaps the last self-identified terrorist group in history. Menachem Begin, the leader of the Irgun gang, categorically rejected the label and instead called the occupying British force the real "terrorists."8 This new-self-description as "freedom fighters" quickly received global acceptance and no group since the Lehi has called itself "terrorist". The members of dissident organizations are acutely aware of the negative image conveyed by the term. A member of the IRA, despite being convicted of several attempted murders, kidnapping, and arms possession, vehemently denied the label: "To me, 'terrorist' is a dirty word and I certainly don't... nor have I ever considered myself to be one, but ah, I remain an activist to this day."9 To him these were political activities separate from those of a common criminal or a loathsome terrorist.

Furthermore, as Rapoport observes, while the dissident organizations eschewed the term, governments around the world realized the political value of calling a dissident organization "terrorist".10 The media in the US, particularly prior to the 9/11 attacks, in order to maintain its neutrality, alternately called the same individual a terrorist, a guerrilla fighter, an insurgent, or a soldier.

Leo Tolstoy in one of his short stories tells the tale of a man who wanted to know everything about the sun. As he continued to stare at the sun, his eyesight started getting affected. He saw the sun getting dimmer and, eventually, one day he could not see it anymore. Frustrated, the man concluded that there was no such object as the sun after all. Those of us who have attempted to study and def...