![]()

Part I

The Nature and Neurology of Cluttering

![]()

1 Cluttering: A Neurological Perspective

Per A. Alm

Introduction

Background

The term cluttering designates a conglomerate of symptoms and characteristics displayed in varying degrees by affected individuals. No single aspect is sufficient to determine the diagnosis; it is the clustering of certain traits that constitute this syndrome1 (see St. Louis & Schulte, chapter 14 this volume). Cluttering is a speech-language disorder, but many authors, such as Weiss (1964), have argued that the symptoms also may include non-verbal motor behaviour, temperament, and attention deficits.2

Research on cluttering is important in order to provide improved means of treatment, but cluttering may also turn out to be a condition that leads to valuable insights regarding the normal processes underlying speech, language, and attention. Furthermore, understanding of cluttering is essential for the understanding of stuttering, as they are overlapping and yet contrasting disorders. Research on stuttering is complicated by difficulties in determining primary versus secondary aspects. This problem is less apparent in cluttering.

The discussion in this chapter is intended to outline a hypothetical framework of how cluttering may be understood. It should be emphasized that cluttering is a heterogeneous disorder, possibly with different causal mechanisms in different subgroups—partly because of unclear criteria for the diagnosis. Hopefully better understanding of the mechanisms involved will result in a more strict definition of cluttering. It is a conscious decision to make the hypotheses quite detailed, which sometimes means being speculative, in order to allow empirical testing.

A Brief Overview of this Chapter and the Conclusions

While the core of cluttering may be seen in the verbal expression of fast and dysrhythmic speech, the understanding of the disorder is likely to involve a very wide range of functions and anatomical structures in the brain related to language, motor control, attention, and intention. There is a lot of information available from current brain research, but there is a need to integrate this, and to relate it to the symptomatology of cluttering. In order to help the reader, the tentative conclusions and suggestions will be summarized here.

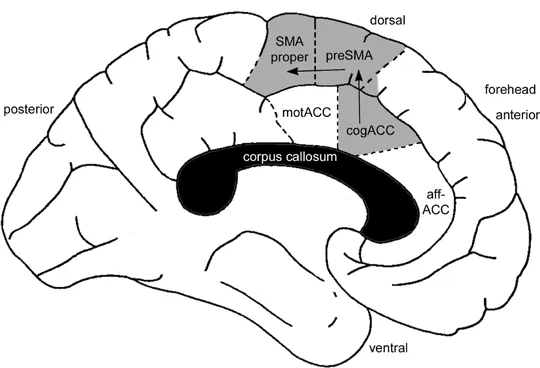

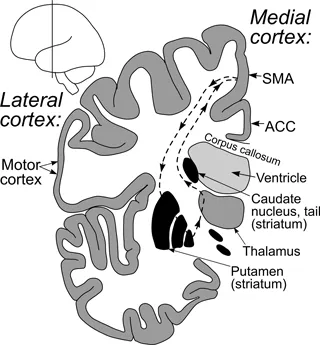

It will be proposed that the core of the problems in cluttering is located in the medial wall of the left frontal lobe, i.e., the cortex on the wall between the cerebral hemispheres (see Figures 1.1 and 1.2). In brief, the model implies that the medial frontal cortex plays a central role in production of spontaneous speech, in parallel with the more traditional speech and language areas in the lateral part of the left hemisphere, such as the Wernicke’s and Broca’s areas. The medial cortex is proposed to have a coordinating role in spontaneous speech, related to the motivation to talk; planning of the phrase; retrieval of words, syntactic elements, and phonological code from the lateral cortex regions; execution of the motor sequence, and monitoring of the speech output. The key regions in cluttering appear to be the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), the preSMA, and the SMA proper, together with the input from the basal ganglia circuits. The ACC is proposed to have the functions of a ‘central executive’, at the core of the initiation of volitional movements and speech, as well as being the centre for wilful attention and high-level error monitoring. The ACC is closely related to the preSMA, which seem to be critical for the ‘assembly’ of the phrase, from the sequencing to the selection of words and word forms. The model that emerges from current brain imaging data is that the ACC, the preSMA, and the SMA proper constitute a hub or an ‘assembly centre’ in spontaneous speech, retrieving all the linguistic components from the left lateral cortex regions, such as the Wernicke’s and Broca’s areas and adjacent zones. The selection of one single word from many competing alternatives is facilitated by the basal ganglia circuits, through a ‘winner-take-all’ function. The timing of the articulation, and thereby the speech rate, is controlled by the SMA proper with support from the basal ganglia and the cerebellum. The production of speech is monitored on multiple levels, primarily through auditory connections to the ACC and the SMA.

Figure 1.1 The medial wall of the left hemisphere. Regions proposed to constitute an ‘executive hub’ for speech production are marked in grey: the cogACC, the preSMA, and the SMA proper. (Redrawn from Talairach & Tournoux, 1988, with approximate division of the ACC added, based on Yücel et al., 2003, and review of data from various studies).

Cluttering may be a heterogeneous disorder, with different (neural) mechanisms in different subgroups. A main mechanism proposed in this chapter is hyperactivation and dysregulation of the medial frontal cortex, which may be secondary to disinhibition of the basal ganglia circuits, for example as a result of a hyperactive dopamine system.

This review and analysis will be divided into main topics that all are intimately interrelated, making the structure somewhat loose. First, the functional anatomy of the medial frontal wall will be briefly presented, in order to provide an anatomical framework. Then the symptoms and characteristics of cluttering will be discussed. Physiological clues from the effect of dopaminergic drugs and abnormalities of EEG lead to a discussion of the possible role of an overactive dopamine system. Thereafter, the review will focus on three main aspects of speech production: (1) initiation and sequencing of action; (2) selection of linguistic items, such as words and syntactic elements; and (3) monitoring of speech errors. The intention is to propose a comprehensive model of speech production, based on current research findings, and relate the symptoms of cluttering to this model.

Functional Anatomy of the Medial Frontal Cortex

Functions of the ACC

The connections of the ACC are characterized by convergence—it is a region where drive, cognition, and motor control interface, putting the ACC in a unique position to translate intention to action (Paus, 2001). This key role in volitional behaviour is shown by the fact that bilateral damage to the ACC results in akinetic mutism, a state without voluntary motor activity or speech (Paus, 2001).

Attention is a function that may be separated into two different aspects: (1) spontaneous attention, elicited by salient stimuli of interest (also known as ‘bottom-up’, where the stimuli is sufficient to catch the attention) and (2) effortful attention, volitionally applied based on motivation to accomplish a certain outcome (or ‘top-down’, for example when looking for a certain object). The ability to maintain effortful attention seems to be dependent on the ACC, especially in case of divided attention (Loose, Kaufmann, Auer, & Lange, 2003). In fact, it seems likely that the ACC plays a central role in all tasks involving aspects of volitional control and attention, such as suppression of automatic responses, decisions under uncertainty, monitoring of behavioural errors, etc. (see reviews of studies in Botvinick, Cohen, & Carter, 2004; Posner, Rothbart, Sheese, & Tang, 2007; Ridderinkhof, Ullsperger, Crone, & Nieuwenhuis, 2004; Sarter, Gehring, & Kozak, 2006). It has been reported that persons with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) tend to have difficulties activating the ACC in demanding situations (Bush et al., 1999). Furthermore, studies have shown that the ACC also is crucially involved in working memory, in a network with the cortex in, and adjacent to, Broca’s area, and maybe other regions (Kaneda & Osaka, 2008; Kondo, Morishita, Osaka, Osaka, Fukuyama, & Shibasaki, 2004; Osaka, Osaka, Kondo, Morishita, Fukuyama, & Shibasaki, 2004).

The ACC receives input related to motivation and drive via multiple pathways, from the limbic system and cortex regions in the lower frontal lobe. Several neuromodulators, like dopamine, influence the ACC, both directly and through projections from the limbic region of the basal ganglia. Strong connections with the prefrontal cortex reflect cognitive functioning. Complex motor behaviours are initiated through the SMA, but the ACC also has more direct motor projections, to the spinal cord and to brain stem nuclei. The more direct motor output from the ACC seems to be responsible for emotional expression, such as laughing and crying (Ackermann, 2008).

Functional Divisions of the ACC and the SMA

The ACC may be divided into three functional regions: the affective, cognitive, and motor ACC (abbreviated affACC, cogACC, motACC; Yücel, Wood, Fornito, Riffkin, Velakoulis, & Pantelis, 2003), from the lower frontal end to the upper posterior end (see Figure 1.1). The core region for the ACC functions discussed above is the cogACC.

The SMA is located at the upper border of the cogACC and motACC. Interestingly, also the SMA follows this division, with an anterior cognitive part, the preSMA, connected with the prefrontal cortex, and a posterior motor part, the SMA proper, with motor functions and direct connections both to the primary motor cortex and to the spinal cord (Johansen-Berg et al., 2004; Picard & Strick, 1996). The activation in cogACC has been shown to extend into the preSMA, for example, in studies of response conflict and error monitoring (Botvinick et al., 2004; Ridderinkhof et al., 2004). It has also been shown that this region (SMA and ACC) responds to speech errors and may detect ‘spoonerisms’ (reversal of sounds) even before they are articulated (Möller, Jansma, Rodriguez-Fornells, & Münte, 2007).

Symptoms and Characteristics of Cluttering

Trying to understand the symptoms of cluttering from a neurological point of view is not a new endeavour. Miloslav Seeman (1970), phoniatrician of Prague, compared the symptoms of cluttering with other neurological disorders, and proposed that cluttering is the result of a disturbance of the basal ganglia system (see Figure 1.2). Similarly, the neurolinguist Yvan Lebrun of Brussels (1996) argued that traits of cluttering after brain damage or disease typically occur after damage to the basal ganglia system, as in Parkinson’s disease.

Figure 1.2 Basal ganglia loops, in a cross-section of a single hemisphere. The schematic figure shows a motor loop starting and ending in the supplementary motor area (SMA), passing through the putamen (part of the striatum) and the thalamus. The figure also shows the tail of the caudate nucleus (part of the striatum) in cross-section. ACC: anterior cingulate cortex.

Behavioural Symptoms and Characteristics

Detailed discussion of the symptoms of cluttering can be found in Weiss (1964) and Luchsinger and Arnold (1965), and more recently in Daly (1993), Myers and St. Louis (1996), Preus (1996), Ward (2006), and St. Louis and Schulte (chapter 14 this volume). Though different authors have a somewhat different focus, the overall picture seems quite consistent. Ward (2006) analyzed the speech errors in cluttering based on Levelt’s model of speech and language processing, and found that cluttering affects all levels of this processing: conceptualization, formulation, and articulation. All elements of speech can potentially be affected, from the drive to talk, the sequencing of the message, the selection of words and syntactic elements, the motor output, and the monitoring of speech errors.

Speech Motor Aspects

The speech motor symptoms are typically characterized by high speech rate, poor articulation with exaggerated blending of adjacent sounds, phoneme sequencing errors (such as gleen glass for green grass, or bo gack for go back; Ward, 2006), and reduced prosody (both timing and pitch range). However, in many cases these symptoms are strongly affected by attention, for example so that speech may sound normal, temporarily, when a tape-recorder is turned on (Daly & St. Louis, 1998). Seeman (1970) mentioned a test he used for diagnosis of cluttering: The patient is asked to repeat the syllable ‘tah’ as fast and for as long as possible. According to Seeman, many people with cluttering (PWC) are able to do this well at the beginning of the task, but after a while acceleration begins and the articulation loses precision. Some PWC also show motor deficits that are not limited to speech, such as in handwriting and general motor behaviour. For example, Seeman (1970) reported a tendency among PWC for rushed and unexpected movements, and general motor restlessness, also during sleep, of choreiform type (i.e., similar to movements seen in chorea, a type of motor disorder linked to disinhibition of the basal ganglia). Another aspect is that PWC often tend to have difficulties in recognizing and repeating rhythmic patterns (Weiss, 1964). (On motor speech activity in PWC, see Ward, chapter 3 this volume.)

Linguistic Aspects

Most descriptions of cluttering include problems with linguistic processing as one aspect (e.g., Myers, 1992; van Zaalen, Ward, Nederveen, Grolman, Wijnen, & DeJonckere, 2009; Ward, 2006; Weiss, 1964), although this does not fall within St. Louis and Shulte’s current working definition (St. Louis & Schulte, chapter 14 this volume). From a linguistic point of view cluttering tends to be characterized by difficulties with: (1) word finding; (2) planning of sentences and phrases; and (3) syntactic elements. PWC often speak in short phrases of a few words, or ‘bursts’. According to Weiss (1964), this is a reflection of the thought process—that the verbal thoughts of PWC tend to proceed by clusters of two or three words at a time, instead of complete phrases. Repetitions of syllables, words, or phrases are common, as well as fillers like ‘eh’ and ‘um’. These repetitions do not seem to occur because of any motor block, but rather as a result of the difficulties to find words and to create a complete phrase. The word order may be incorrect, and sentences may be left unfinished or continue in a ‘maze-like’ fashion, leaving the listener behind. Retrieval of words, including names, prepositions, and pronouns, may be inexact, so that an incorrect word is chosen based on similarities in sound or semantic content, such as plant for point, or fork for knife. Function words may be omitted and the verb conjugation may be incorrect (Ward, 2006).

Attention, Temperament, and Social Interaction

A typical trait observed amongst PWC seems to be reduced attention to sensory input, displayed as poor monitoring of one’s own speech production with limited awareness of cluttered speech, as well as insufficient attention to the listener. The observation that attention to speech often results in temporary normalization indicates that the necessary linguistic and motor functions may be available, but require focused attention.

Regarding personality, Weiss (1964) claimed that PWC are generally of pleasant temperament. Other traits that have been proposed to be frequent among PWC are impulsiveness, impatience, excessive talking, and being short-tempered (Daly, 1993; Weiss, 1964). One way to analyze temperament and motor functions is in terms of inhibition versus disinhibition. From this viewpoint, the traits mentioned above seem to be associated with disinhibition. However, it is important to avoid generalizing a ‘cluttering stereotype’, because PWC do differ in these respects (see also Reichel & Draguns, chapter 16 this volume).

Cluttering is defined as a speech-language disorder, but it seems likely that people who primarily have a mood disorder, such as mania, sometimes have been (mis)diagnosed as clutterin...