![]()

1

What is The “Web” in “Web 2.0”?

A short history of the Web

Today, many people use the terms “Web” (short for World Wide Web), “Internet,” or “online” interchangeably. “I got this song online.” “I got this from the Internet.” “It’s from the Web.” These all work. They do a good enough job of conveying the meaning of the speaker. The terms World Wide Web and the Internet, although they are related, are distinct technical entities; as phenomena in the computing experience for most users, however, this is of little consequence. One of the aims of this chapter will be to make this distinction clearer and also argue for its significance.

It may be helpful to think of the Web as a part of the Internet. The Web is a set of hyperlinked documents and pages on the Internet. This is most intuitively understood by looking at the URL of any given website or blog. Most Web addresses use hypertext transfer protocol (HTTP). On occasion, some users of the Internet, especially those who are proficient enough to manage their own websites or blogs, have to upload files to their site or blog, and must access an address using the file transfer protocol (FTP). These two protocols are part of what is called the application layer of the Internet protocol suite, alternatively called TCP/IP (transmission protocol/Internet protocol). While space does not permit delving more deeply into the intricacies of these various protocols, it is important to note that “the Internet” is more than what exists within the rectangular frame of the Web browser. There is a complex architecture underneath it all. If looking at the World Wide Web as being a part, but not a component or element of the Internet is not the best illustration, perhaps we can say that the Web is one way of experiencing the Internet. Think of the Web as being the top-most layer. It is how most proficient but not expert users experience the Web. It is like an island, which, in spite of appearing as if floating on the water, extends down to the ocean floor.

Behind the situation that occurs today, i.e., where the “Web” is equated to the “Internet,” there lies a complicated history. To detail it and do it justice would take an entire book. The aim of this chapter is to condense the most important aspects of this rather complex history and extract certain moments that are particularly important for the topic of this book–Web 2.0. Although it is arguable that all developments in the history of the Internet and the World Wide Web contribute to the current regime of social media, we would contend that there are specific moments that are more important than others.

The overarching aim of this chapter will be to give a brief history of the World Wide Web and the Internet, and to situate Web 2.0 within this trajectory. To accomplish this, we begin with a brief “pre-history” of the World Wide Web, detailing the Internet prior to the visual interface known as the browser. We then move on to the history of the World Wide Web (the “Internet” as most of us know it). Here, we spend time highlighting some of the technical and experiential (or user) differences between Web 1.0 and Web 2.0. We conclude with a brief assessment of the open-source movement, looking especially at Wikipedia, which has most often been identified as embodying open source and Web 2.0, par excellence.

A Pre-History of the World Wide Web

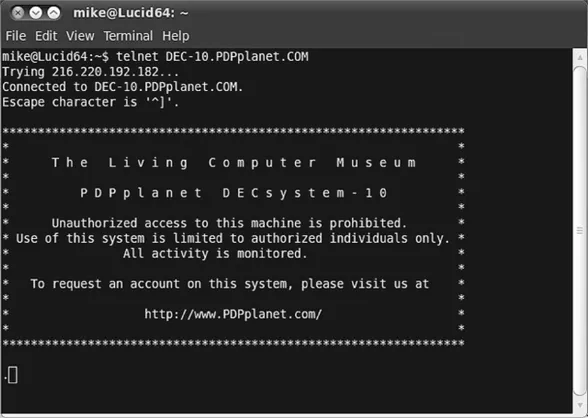

The World Wide Web is a graphical interface for the Internet. Prior to the graphical interface and the use of browsers, such as Internet Explorer, Mozilla Firefox, and Google Chrome, the Internet was accessed mostly through something like Telnet (short for terminal network), a text-based network protocol that allowed for bidirectional communication, which looks a lot like MS-DOS because of its command-line interface. (See Figure 1.1.) It looked very different from the Web that we are used to today.

Figure 1.1 Telnet, one of the first graphical interfaces (Source: onala [http://www.flickr.com/photos/onala/]).

This blackbox, which by today’s standard would be the very definition of poor user interface in the terminology of human–computer interaction (HCI), is nevertheless one of the first graphical interfaces, although in most histories of the Internet and the World Wide Web, “graphical” refers to entrance of images and video (not text) on a Web page.

The history of the Internet, therefore, reaches further back than that of the Web. Although there is some disagreement on the matter, many scholars and journalists alike place the date of the “inception” of the Internet to 1969. On 2 September 1969 two computers on the campus of UCLA transmitted data back and forth on cable. A month later the computers from UCLA connected with those 300 miles away in Stanford. This is the beginning of the ARPANET, a network that was supposed to link different researchers around the USA who were working on projects for the Pentagon. ARPA stands for Advanced Research Projects Agency, a wing of the Department of Defense.1

The idea of the interconnected networks, however, had existed since at least J.C.R. Licklider’s memos on what he called “Intergalactic Computer Network” published throughout the 1960s. Licklider, a computer scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and also the first head of the information processing office of ARPA, wrote of a global network of computers that would allow users to access data and programs from any point in the network. The implementation of packet switching aided the actualization of Licklider’s vision of the computer as a communicative device occurred with the successful establishment of the ARPANET network, which eventually added UC-Santa Barbara and University of Utah to the mix.2

The computers in the ARPANET network were able to communicate, that is, transmit data, with one another through something called “packet switching.” Simply, packet switching is a means of slicing data of all kinds (text, graphics, audio or video) into discrete blocks. The network can route the blocks independently of one another, depending on the resources available at that moment. Packet switching is advantageous because of its efficiency; that is to say, it makes the best use of the capacities of all of the links in the network. More importantly, it ensures that the message will always get through since there are so many different routes a single packet can take. This is in direct opposition to previous a form of networking, circuit switching, which could not send the message successfully if there were a problem with one.3

Additionally, an important advantage of packet switching was that it embodied a concept known as open architecture. Open architecture is an idea that allows for various networks to connect with each other, in spite of their particularities. In an open-architecture network, networks did not need to be designed under a single rubric but could be individually designed and developed. Networks could be interconnected without a hierarchical relationship. Open architecture made it so that identity was not the condition of possibility for communication but allowed for difference. Therefore, networks that were not necessarily created, designed, and maintained by ARPA could, in theory, connect with it. But this is not as easy as it sounds, especially for those of us who have grown up in the era of technomedia, where a basic amount of interoperability is not only expected but also crucial.4 In 1972, Robert Kahn and Vinton Cerf solved this by moving the responsibility of controlling how, and checking whether, packets had been transmitted from the software in the network to software on computers that were sending and receiving packets. Although this was a relatively small tweak, it had major consequences, building the foundation for what is today called TCP/IP. “[N]etworks of one sort or another all became simply pieces of wire for carrying data. To packets of data squirted into them, the various networks all looked and behaved the same” (Economist 2009).

From this followed various developments in Internet use, which are significant for how we use and think about the Internet today. The most significant is perhaps the advent of email, developed by Ray Tomlinson, who first decided to use the @ symbol to divide the user name from the computer name, which later became the domain name. Another, just as important development is the use of the Internet for content storage. Project Gutenberg began to store entire books and documents in the public domain available electronically. Email and Project Gutenberg are significant moments in the pre-history of the World Wide Web.

Additionally, there was the introduction of the Bulletin Board System (BBS), the first discussion forum in 1978, as well as the first Multiuser Dungeon (MUD). This of course led to other virtual communities such as Whole Earth ’Lectronic Link, simply the WELL.5 A decade later came the Internet Relay Chat (IRC), a precursor to chat rooms and instant messaging, which allowed for real-time, synchronous messaging. Further, it also allowed for data transfers, which could be viewed as a primitive form of peer-to-peer networks in the vein of Napster. Although they preceded the Web proper, they were nevertheless harbingers of how the Web would be used—for communication and information search.

The Emergence of the World Wide Web

In 1989, Tim Berners-Lee at the European Centre for Nuclear Research (CERN) drafted a paper titled “Information Management: A Proposal.” In it, he visualized a model for how to manage the utterly immense amount of information for various projects at CERN. The idea was to convince CERN of the benefits of adopting a global hypertext system, which had been developed by Doug Engelbart in the 1960s, to manage information. CERN approved his proposal and by 1991, along with his colleague Robert Cailliau, Berners-Lee had written the basics of a hypertext graphical user interface (GUI), using software called NeXTStep. The rudimentary elements of this code are still used by Web designers today—HTML, HTTP, and URLs. He named it “WorldWideWeb.” The first Web page was, indeed, a page explaining the Web.

The mid-1990s signaled the explosion of the World Wide Web into the mainstream, with the development of the first graphical Web browser available to the public, Mosaic, which was quickly followed by Netscape Navigator. Many business observers have identified the period of the 1995–2000 as the dot-com or IT bubble. Castells has alternatively called it the IT revolution of the 1990s. In this period, we saw the takeoff of a variety of internet service providers, including America Online, Compuserve, and Prodigy. Their incredible rise was intimately bound to the popularization of the personal computer, which by the 1990s had reduced in price and in size significantly enough where households were beginning to purchase them, not just offices. Importantly, these personal computers also came with a modem, which allowed the computer to connect to the Internet through a telephone line. By the mid-to-late 1990s, websites had become a common feature of many business and organizations. With the launch of Geocities, individuals could have their own Web pages. This is particularly important as individuals and business were virttually on the same footing when producing content for the Web. Not long after this event, personal Web pages would turn into online diaries or Web logs (or just blogs), with services such as Xanga LiveJournal, which allowed for the creation of a blog with minimal technical expertise. Web-based email came not much longer afterwards with Hotmail. Although search engines had existed prior to it, Google’s emergence marked a key moment for the early Web.

As you can see, the Web represents two things in the history of the Internet. For one, it is the remediation of the Internet. Various aspects of the Internet, including email and virtual communities, were remediated onto the Web. This may sound as if we are underplaying the significance of this fact but quite the contrary: the movement of these various functions to the World Wide Web is something like a massification of the Internet. To be clear, this is not to say that the World Wide Web popularized the Internet on its own. But it did provide a means for non-experts to get online. This was, as mentioned earlier, aided by the decline in price of personal computers. Nevertheless, prior to the Web and the Web browser, the Internet was for those with the means and the knowledge to be able to use them. It was an “expert system” (Giddens) par excellence. The Web allowed for those with basic computing skills and familiarity with the interface of the desktop.

The World Wide Web, up until the dot-com bust of 2001, could be seen as engendering a certain set of values for its users. That is to say, the Web in this period was used mainly as an information culler. An early ISP, Prodigy, in particular, called itself the first consumer online service, since it offered an intuitive graphical user interface. But the main uses of Prodigy were to receive information—weather, sports scores, stock information. Although there was undoubtedly “interactivity,” which had separated the Internet and the Web from prior media, there was no “content creation.” Users of the Web could interact with one another and partake in chat rooms and discussion threads, and have encyclopedic information at the touch of their fingertips. “Web 1.0,” then, can be characterized by information consumption.

We hesitantly label this period Web 1.0 since it gives the air of linear progress, making the years leading up to the end of the millennium as some kind of precursor to the messianic appearance of the social Web.

This is far from the case.

There are plenty of products, services, and trends dominant during the 1990s that are merely figments of the imagination for those of us who were actively on the Web at the time. The chat room is the butt end of jokes today. Blog comment sections have overtaken discussion forums. The “becoming-social” of the Web is not, we would suggest, the sole actualization of an intrinsic social nature of the World Wide Web. While it is undoubtedly the case that the Web and the Internet generally have always had a social aspect, Web 2.0 is a phenomenon that can best be explained as a confluence of commercial interests, the technological bias towards sociality intrinsic to the Internet, and the always unexpected ways in which people create new ways of using technology, which were either unforeseen by their developers or even forbidden.

One such case is, of course, file sharing. With the rise of Napster, famously created by a college student in 1998, the term “piracy” instantaneously became associated with the Internet. Although Napster was not Web based, since it was a standalone application that connected different computers via the Internet, allowing various computers to share certain files (mostly music files), it is certainly an important moment in the later development of Web 2.0, as it served as a lightning rod, marking a div...