Chapter 1

Introduction

I have been a qualified chartered architect for over 30 years, and in that time I have designed and overseen the construction of countless projects. In the main, these have been commercially based schemes, ranging from individual or complex apartment blocks, town-centre schemes, offices and schools through to industrial complexes and airports.

Through that experience, I have been involved in detailed work to develop the best solutions for the client and to ensure that the answers provided are regulation-compliant and best value for money.

I have always been interested in the balance between good design and functional excellence. The skills the designer needs to conceive the best solution are considerable — however, in this increasingly complex world, we also need to be able to convince the client and the construction team that the design is valid, practical, good value, and therefore viable.

However, the result of this process often involves a compromise as a result of the many debates and pressures that affect the construction industry today. These may sometimes play out positively, but often negatively, and we all are the poorer for it.

I have always considered the technical and practical aspects of the profession to be the most challenging. ‘Form follows function’ has been the mantra of many an architect, and is as valid today as ever.

Throughout the whole of my career, I have been concerned over the use or misuse of materials and the squandering of energy. In the early part of the twenty-first century, we seem to have returned to the same issues that I started out with in the 1970s, when Schumacher, Brenda and Robert Vale, Alex Pike and others were making the case for more rational use of resources. We are now revisiting many of these principles under the heading of sustainability and — possibly humanity’s single greatest challenge — taming the use and proliferation of carbon (and related gases) and its effects on our planet’s climate.

I hope, through this discussion of some of the aspects of whole life values, to develop this debate into a more considered and applied approach that will deliver some tangible and meaningful results.

The need for whole life costing

There has long been a need for greater understanding of materials and resources, and how we use them. As with many issues in the construction industry, this question has been hijacked by third parties, in this case the ‘whole life costing lobby’.

In theory, this has produced a raft of information that is supposed to identify the life of the cost of a building, and the cost of the life of that building.

In the real word, however, this is rarely relevant — the normal outcome is to pare costs to the bone, or to justify poor material choices. By the time the results of these decisions have surfaced, those who made them are long gone, possibly retired. We therefore have the construction equivalent of the ‘emperor’s new clothes’.

This book attempts to clarify this central challenge and to offer some solutions to this dilemma. This is a book rooted firmly in the real world, confronting the real challenges that affect construction professionals on a daily basis. It is intended as a management and project guide that will offer real benefits to projects in the future. It offers:

-

an explanation of the workings of the construction industry today

-

an account of how circumstances have developed in combination with the practicalities of construction

-

some key principles to ensure that sensible analysis can be undertaken to arrive at a real whole-value view of a project.

These factors all have a foundation in financial issues, but are all practical and quantifiable.

So why is life-cycle costing so rooted in money? I suggest that this is largely because the issues involved have been taken over by the financial part of the industry. The client’s ear is always open to money matters, and whole life values in themselves are difficult to get on the agenda. We are therefore left with an analysis that is largely removed from the real, practical, everyday world, and will mainly be public relations (see Chapter x ). Central to the practicalities of this subject is the characteristic of ageing.

Why is whole life costing important?

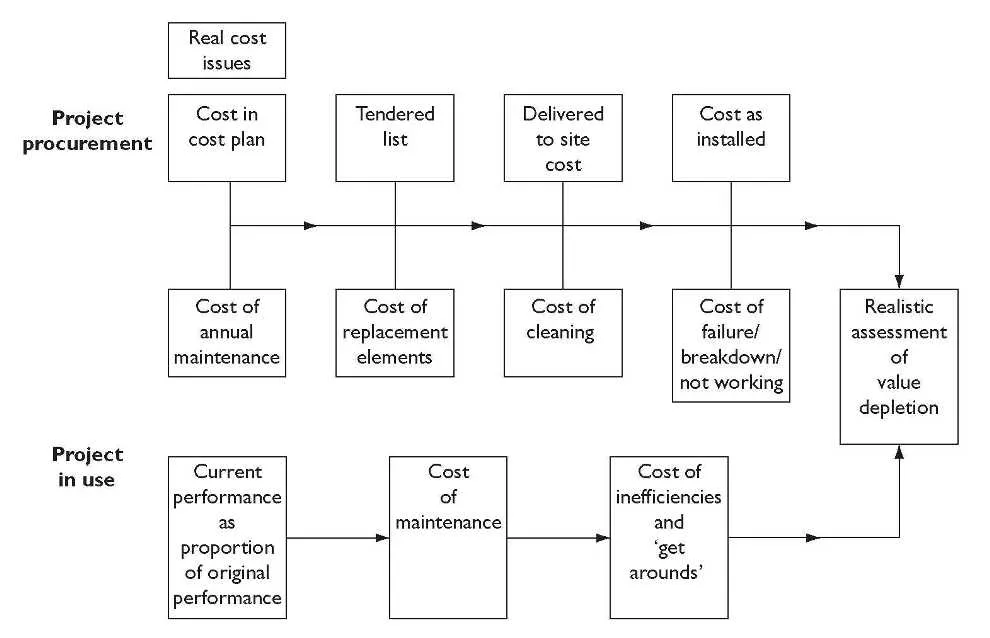

Today, so much of what we construct is based on a short-term perspective, and the cost plan is completely dominant. Most project models, especially in the commercial world, are formulated around the principle of units and the cost of those units. These are later developed into elemental costs, and then into a cost plan.

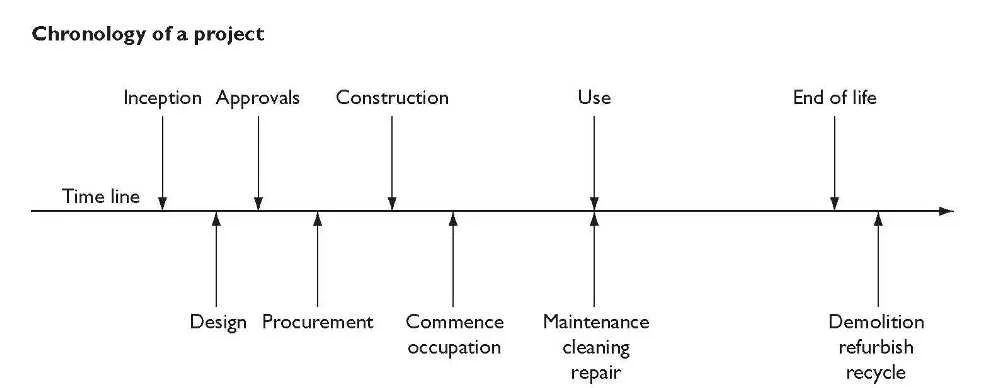

Figure 1.1 The project life cycle

For many designers, this is unhelpful and disjointed, the relationship of the cost plan and the design being entirely out of step. It is easy to point the finger at the cost consultants here — but the truth is that all members of the design team are usually to blame. Seeing the whole picture, or caring about the requirements of other disciplines, is disappointingly rare. The inevitable consequence is a design that is underdeveloped and a cost plan that is based on too many assumptions — a model that is firmly rooted in short-term profit.

It is for these reasons that the financial detail will not coordinate with the design, any fit between them being very much a matter of chance. This is, of course, both short-sighted and regrettable. The focus is entirely on money. Using finance as the driver to reach more rational conclusions, but not to derive a solution, as most seem to do, is hardly rational. Confused and irrational, these methods just serve to compound the problem.

This book aims to set out a more rational process, away from the financial issues, and to focus on the practical, physical issues that actually establish the whole life cost of buildings and their components. Logically, delivering a real whole life analysis must surely benefit the project and the client, as well as the reputation of the team. In the long term, this must be the only way forward.

Cost is important, of course, but it must be seen in context of the project as a whole, not as a result of — nor the driver for — whole life costing. All forms of analysis to date use a multitude of assumptions to establish a financial statement. This is then used to establish the whole life potential of a particular course of action. How can this possibly be of any real benefit, or in the least way accurate?

It is better to focus on real-world issues to establish the potential, and then to identify whether this is a cost worth paying, and whether it is affordable or even achievable. All too often, the paper principles may not even be achievable, and this cannot be a sensible way to proceed. We need to take action now — if not, we will be forced into reactive measures in future decades.

First, the logic of what is useful and what is not needs to be determined. There is no point in devoting large amounts of resource to analysing a project for it to be so entirely theoretical as to be meaningless. We should be asking at the start: what is the point, where will this benefit the building, or the client, or the end users? Quality of work and maintenance is crucial to all of this, and without a clear understanding of what is required and what can be delivered, there is no point to the exercise. Ensuring that these factors are controlled and undertaken in accordance with the project plan is fundamental. But currently there are few drivers.

Predicting trends in future materials, fashions and commercial pressures is also a complex area. Without some understanding of these, it is difficult to see how any assessment will be of use.

By looking in detail at all the factors involved, a useful model can be produced that allows a range of outcomes to be identified. This can then be used to determine the specification and building operation procedures to deliver the anticipated outcome.

What are whole life cost and whole life value? What benefits do they have? It is important to at least try to estimate the answers, even if flawed.

Any project requires resources. At the beginning, these include the design team and construction processes. For any client requirement, there are a multitude of solutions that will arrive at more or less the same result. However, the details as applied can result in wide variations as to how the building will perform in use, and how long it will last. Additionally, the level of maintenance a building needs to continue to perform will vary, as will the level of maintenance that an owner or occupier carries out. This, too, will have a substantial effect on the life of the building.

There is no single answer to the whole life question. Many variables give rise to a completed project, which will then be subject to many others, all of them affecting the life of the building.

The conundrum does not stop there. How exactly do we establish ‘life’ and quantify the values of the issues affecting it? This is where fiscal methods alone are inadequate — there is a need to take into account all the various factors to arrive at anything like an accurate answer. For example, it is questionable when a building’s life ‘ends’ — buildings can often be refurbished and reused, which changes the original estimates of whole life value and can change the entire model.

These are difficult issues, certainly, but careful analysis can give some useful results. Linking this with the need to be more careful over the use of materials and energy work done in this area is crucial to the future of appropriate construction. Sustainability and carbon are also part of this story.

It is possible to make some clear statements about what is, and what is not, whole life cost and value, which help to separate the useful from the irrelevant.

Whole life cost is:

-

a true assessment of the worth of a building, within limits

-

a theoretical judgement using the best information available

-

a process to balance the design procurement and use factors

-

a process to place cost in perspective as one important element

-

a process to be used with care, as results will be a guide only

-

useful as part of the analysis to arrive at whole life value.

Whole life cost is not:

-

accurate — it should not be relied on to set a business case

-

the only measure to assess ...