![]()

1

Rebuilding after disasters

From emergency to sustainability

Gonzalo Lizarralde, Cassidy

Johnson and Colin Davidson

There are various misconceptions in both the theory and the practice of reconstruction after disasters. First, natural disasters are not really natural (in the sense that they are not exclusively the result of natural phenomena; they are the result of the fragile relations between the natural and built environments). Second, contrary to common belief, evidence shows that effective rebuilding does not necessarily depend on the speed of construction, and it does not always benefit from the usual separation into three different phases: emergency housing, temporary housing and permanent reconstruction. Even more surprising, this evidence shows that the most important contribution of architects and other specialists does not come from where it is commonly believed to (design and construction) but instead from a proper understanding of the roles and capacities of the multiple actors involved.

From emergency …

In the earthquake I was with my wife, Rubiela, in the town, and we were surprised to see the houses falling down. … we almost had to walk back to the farm as there was no transportation. When we arrived, I felt happy to know that my family was alive, but at the same time very sad to see the house totally destroyed … We thought we could not rebuild our house again because we didn’t have any resources …

Oscar Bermudez, citizen and farmer of Calarcá, Colombia, when asked about his experience in the earthquake.4

The experience lived through by Oscar Bermudez is repetitively shared by millions of people worldwide. Sadly, it is probable that – in the next few years – there will be another disaster in the Andean region of Latin America, on the Pacific coast of Central America, in Europe, in southern Asia, in Central Africa and in many other regions of the world. The majority of the most devastating of these disasters will occur in cities of the developing world. Houses, infrastructure and public facilities will probably have to be rebuilt quickly and in a situation of emergency. Certainly they will have to be built amid a period of stress and disorder and with limited resources. Hopefully they will be built in a way that provides sustainable environments with improved conditions for this generation and for those of the future.

This is a major challenge for the professionals of the building industry, particularly in developing countries. This book deals primarily with the actions required after the disaster has occurred, but it is based on an understanding of the complex relations between post-disaster interventions and pre-disaster mitigation and prevention. We emphasize the role of the built environment (particularly the provision of housing) in the rebuilding of lives and sustainable livelihoods after disasters. The contributions in this book concentrate on the principal challenges facing the professionals and practitioners of the building industry, but they also highlight the relationships between the building industry and other areas of intervention, including humanitarian aid, medical assistance and economic reconstruction. The contributions bring into focus the complex and dynamic relations between societies, space and urban development.

The arguments in this book are based on empirical research and experience “from the field.” This book is not built upon theoretical discussions and guidelines of how things should be in an ideal world (i.e. how people should participate, how governments should react, how professionals should perform, etc.) but rather upon how things are actually done and how doing them can be improved within the real constraints and challenges that are common both to the building industry and the humanitarian/development sector. The contributors to this book recognize the links with other areas of intervention, but they respond with straight answers to questions that frequently arise among the professionals of the building sector, such as: How can we, as professionals, react to a disaster situation? How can we improve post-disaster reconstruction? What are the roles of architects, engineers and development practitioners after disasters? What are the roles of government actors and non-governmental organizations (NGOs)? What is the role of local communities and how can it be respected?

In order to answer these questions, it is very important to distinguish common misconceptions or myths from factual realities of reconstruction. This book challenges, among other subjects, the following myths:

• the fact that disasters are natural (though they do follow natural events);

• the common belief that effective rebuilding depends on the speed of construction;

• the notion that housing reconstruction should be separated into three separate types – emergency, temporary and permanent;

• the idea that there are two dominating paradigms – bottom-up and top-down;

• the belief that community participation holds the key to successful reconstruction;

• the preconception that prefabrication and industrialization should be avoided;

• the idea that centralized decision making is the key to effective housing provision.

The field of reconstruction – both theory and practice – is filled with concepts that together amount to evolving paradigms; they sometimes help to clarify the real problems and assist the search for systemic plans of action, and sometimes their effect is exactly the opposite.

Reconstruction after “ not-really-natural” disasters

It is commonly accepted by international organizations that a disaster is “a serious disruption of the functioning of a community or a society involving widespread human, material, economic or environmental losses and impacts, which exceeds the ability of the affected community or society to cope using its own resources.”36 Even though there is little controversy about this definition, it does not sufficiently explain why disasters happen. In other words, why is there a limit of destruction beyond which societies cannot cope with their own resources? To explain this limitation and explain the causes of disasters, geographers, anthropologists and other specialists in social sciences have developed the concept of vulnerability.3,10,23 They examine the various physical, social, economic and environmental factors that lead a community to a certain level of “weakness” such that a hazard leads to a level of destruction from which the community cannot recover without external intervention.

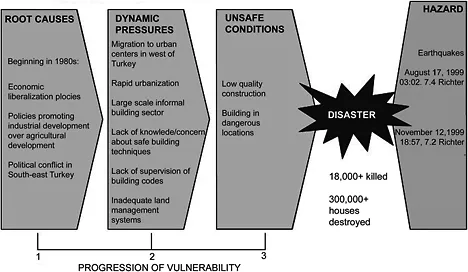

The United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction defines vulnerability as the “the characteristics and circumstances of a community, system or asset that make it susceptible to the damaging effects of a hazard.”36 The concepts and definitions of vulnerability are still evolving. One well-regarded vulnerability model, the “pressure and release model” developed by Ben Wisner, Piers Blaikie, Terry Cannon and Ian Davis, describes how vulnerabilities correspond to unsafe conditions originating from existing dynamic pressures (caused by social, political, economic and cultural factors in the system).3 Very often, these dynamic pressures originate in political, economic or social circumstances, which are called “root causes.” According to this approach, when unsafe conditions meet with a natural hazard (earthquake, floods, landslides, etc.), a disaster occurs. Figure 1.1 shows – as a way of exemplifying this argument – the vulnerability model applied to the 1999 earthquake in Turkey.

This understanding of vulnerability is useful for identifying the macro-scale causes of disasters through the accumulation over time of unsafe conditions (Lee Bosher further discusses this issue in Chapter 12). However, models of vulnerability indicate very little about what type of actions are required to overcome the disaster once the natural event coincides with the accumulated vulnerability. In this book, we look at the concept of vulnerability from the perspective of post-disaster recovery. Vulnerability can be understood as a

lack of access to resources (either material, such as finance, housing, roads, infrastructure, public services, etc., or organizational, such as insurance and the individuals’ decision-making capacity, education, information, etc.). Thus inherently unsafe conditions and dynamic pressures in the social and physical environments also correspond to inappropriate or insufficient access to the resources that permit a community to deal with the effects of hazards.

Approaching reconstruction in this way not only builds upon the concepts and ideas elaborated by previous research but also permits taking a step forward in identifying what the role of reconstruction is after a natural hazard.3,10 It is very often believed that reconstruction is “[the group of] actions taken to re-establish a community after a period of rehabilitation subsequent to a disaster. Actions would include construction of permanent housing, full restoration of services, and complete resumption of the pre-disaster state.”34 This concept has frequently been accompanied by the idea that the reduction of the vulnerabilities and sustainable reconstruction are only achieved through the reinforcement of local strengths. “The key to success ultimately lies in the participation of the local community – the survivors – in reconstruction” argued the United Nations Disaster Relief Organization (UNDRO) in a paramount publication in this field published in 1982.35

It is usually recognized that there are two types of resources that determine the “level of development” a community has: (i) “hard” resources (this describes tangible and physical resources such as housing, infrastructure, public services, etc.) and (ii) “soft” resources (this describes non-tangible or non-physical resources such as employment, education, information, etc.). However, if one considers that vulnerability is the lack of access...