Introduction

The background to this book is the consolidation of awareness that what we consider a disaster can be interpreted in terms of development, and that the right type of development reduces disasters. The book explores the reasons why we should focus on disaster reduction and sustainable development as part of the same agenda. It introduces many of the key ideas, terminologies, implications and applications that are part of the interconnected world of disaster and development.

Whilst this book was being written, numerous recognised disasters were reported from around the world. Those that reached the press included the rapid onset events of Cyclone Sidr in Bangladesh on 15 November 2007, Cyclone Nargis in Burma on 2 May 2008 and the Wenchuan Earthquake of Sichuan Province, China on 12 May 2008. These largely unpredicted examples alone accounted for an estimated 90,000 deaths and about 25 million people being displaced from their houses. Given the level of destruction that occurred, many of these people lost their homes on a more permanent basis. Instability, displacement and economic destitution also continued for many more millions in other parts of the world, including the Democratic Republic of Congo, Zimbabwe, Sudan, Somalia, Iraq and Afghanistan. Across the Horn of Africa, the World Health Organisation (WHO) was estimating by mid-2008 that about 15 million people were facing a combination of drought, armed conflict, high food and fuel prices, and a succession of poor harvests (WHO 2008b). In September 2008, the annual cycle of cyclones were hitting the Caribbean and Southern United States, again reminding people that few areas of the world, whether associated with high, medium or low income, escape environmental hazards. There are many other events that have been dragging on over a long timeframe, such as persistently high infectious disease incidence, development induced displacements (i.e. related to dam, construction, agrarian changes or deforestation) or smaller more localised disaster events that only make it into the local press, or remain unreported. In each instance, a variety of perspectives are used to explain the circumstances that occurred before, during and in the wake of the disaster event.

The causes, impacts and longer-term consequences of disasters are often brought to the attention of an international audience that is experiencing increased connectivity through telecommunications and travel. This occurs alongside personal experiences of crisis, concern about the pace of change we are witnessing, uncertainty about the future and a sense of disaster risk being out of control through climate change. It has led to an upsurge of interest in explanations for disasters, and the means to their reduction. With the emergence of such a wide interest group, one common observation has been that major disruptive events are best approached using varied expertise and knowledge. There have been significant contributions to disaster studies over the decades from disciplines such as geography, environmental studies, economics, sociology, public health and planning. The disaster and development perspective outlined in this book confirms these and links that can be wider still. The field of disaster reduction concerns prevention strategies, political will, community actions, rights, critical infrastructures, survival strategies, relief and recovery, behaviour, perception and health, to name just a few. In this context, we have learnt that supposed ‘expert knowledge’ can at times mean a conundrum of missing information and failed expectations. After all, expert knowledge has not been ‘expert’ enough to prevent the disasters of our times. Increasingly, the role of local knowledge, grounded in local realities, provides a crucial component of the subject area. This is often beyond the reach of the formalised academy and of textbooks. Further interpretational nuances of disaster and development are to be found within ourselves, influenced by our hopes, aspirations and roles in securing wellbeing now and for future generations.

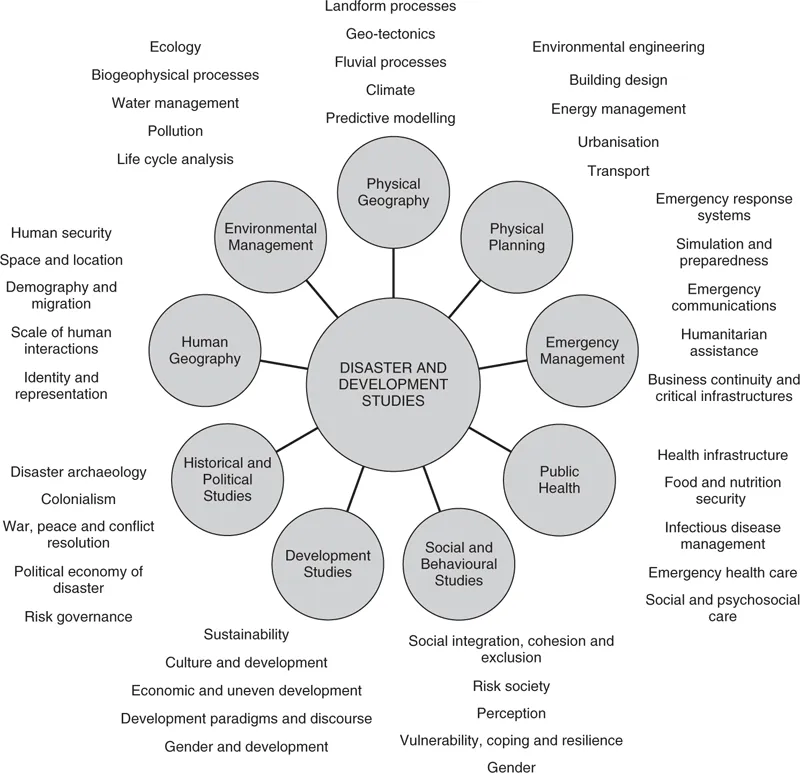

The more formal and extensive disciplinary terrain supporting this subject includes the topics represented in Figure 1.1. A selection of key topics has been included alongside the academic classification with which they might

be suitably identified. It is recognised that topics in nearly all instances can be situated in more than one of the broad subject classifications.

Overview of the book

The book addresses how we can approach and apply a disaster and development perspective in an integrated way for engaging some of the major crises of our times. Disasters in the context of development are considered to be any severe disruption to human survival and security that overwhelms people’s capacity to cope. This definition is broadly in line with some of the more recent policy documents on disaster reduction of international and national development institutions, some of which are referenced in this chapter. Guidance is provided at the end of each chapter on further reading. A key purpose is to demonstrate throughout the importance of addressing disaster and development perspectives together, as two sides of the same issue.

Chapter 2 addresses the disaster and development link from the perspective of how different types of disaster can be viewed from different perspectives of development, including historical and contemporary, economic, social and environmental viewpoints. The chapter starts with the early Malthusian predictions that by this century the world’s population would have fouled its own nest beyond the limits of survival. However, development has to date in many ways staved off disaster through technology and through adaptation. Views on basic development theories are presented in terms of their contribution to disaster adaptation or otherwise; through avoidance of disaster, mitigating disaster impact, and post-disaster recovery. This includes an account of disasters and (1) the logic of economic development, (2) the dependency of poorer nations and (3) the link between poverty and environmental degradation. The contexts of urbanisation and globalisation bring new hazards, vulnerabilities and risk governance issues to bear. Different development paradigms coexist rather than replace each other, such that underlying causes of vulnerability to disaster must be interpreted in terms of complex development processes.

Chapter 3 conversely addresses how disasters influence development. Disasters cause extensive loss of life and livelihood, slowing development or setting it on a backwards trajectory for months, years or decades. The typology of disasters is addressed based on their nature and impact on development. Ultimately the definition of disaster is to do with human security. Loss of human security (food, health, environmental, livelihood, social, personal) prevents sustainable development. The process of losing security occurs through loss of capital assets. The chapter introduces these assets (human, social, natural, physical and financial) as being influenced by environmental catastrophes, conflicts and complex political emergencies. The chapter also includes a well-honed sentiment that disasters also result in opportunities. The old adages that adversity brings out the best in people and that necessity is the mother of invention can be exemplified in local responses to disaster. Whilst insecurity is overall bad for development, the reality is that, under pressure, people cope and become resilient, reducing disaster impacts significantly. However, policy environments, such as, for example, those relating to resettlement and refugees, are often not conducive to letting people rebuild their lives, therefore constraining development. Emergency relief and development work is limited if it does not recognise what is meant by local coping and resilience. This raises a deeper problem concerning the categorisation of disaster survivors as helpless victims rather than capable people. Importantly, in responding to disaster issues, representation of a ‘disaster’ by the media has a significant influence. This can have a direct bearing on when and how aid ends up being delivered, with consequences for development in the recipient areas.

Chapter 4 provides a focus on health disasters, and on health disaster prevention. A chapter dedicated to this topic is not difficult to justify. Whilst disease remains the largest cause of mortality and morbidity in the world, and is increasingly included as a disaster category, different aspects of health (physical and mental) provide both actual and analogous representations of disaster and development. Whilst incidence of disease in an endemic region becomes regarded as the norm, deviation from regular occurrences is considered an epidemic. This leads to subjective interpretations as to when an endemic or epidemic situation might or might not be considered a disaster, a conundrum with resonance across the disaster reduction field. ‘Common’ diseases of poverty, such as diarrhoea, become ‘acceptable’ and persist, whilst new disease risks with low death tolls, such as CJD, SARS and bird flu, are considered a major disaster threat and worthy of significant financial investment. The human immunodeficiency virus and accompanying acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) provide a poignant example of where disease disasters hold back development, such as through the death of high percentages of the economically active age group in sub-Saharan Africa. However, strategies aimed at better living with HIV/AIDS, with the use of antiretroviral drugs, are beginning to spread hope of longer-term recovery from the effects of this disease on society.

Well over half of infectious disease incidence is associated with food and nutrition security, the precursor to famine disasters and ultimate indicator of insecurity and underdevelopment. This is usually aggravated by drought rather than being a direct consequence of it. With global calorie supply outstripping demand in recent years, famine should be considered an avoidable slow onset disaster, the progression of which is symptomatic of the failings of uneven development. Psychosocial influences accompany all disasters, but are often neglected or misunderstood. Biomedical and more culturally based approaches to addressing trauma contrast with each other. Whilst primary health care (PHC) is a mainstream of development, its basic principles get modified for health care in emergencies. There are direct links between preventative health care, disaster risk reduction and environmental care, and the ideology of primary health care translates closely to current disaster risk reduction thinking.

The three chapters that follow focus on applied aspects of the topic, familiar to the experience of many disaster management and development practices. They address the learning and planning process in disaster management (Chapter 5), early warning and risk management approaches and techniques (Chapter 6), and disaster mitigation, response and recovery (Chapter 7).

Chapter 5 represents a ‘learning by doing’ approach, exemplified by the project cycle and, in the wider sense, by an interpretation of the disaster management cycle. Review and evaluation of development are paralleled to some extent by the process of review and lessons learnt post-disaster. Both processes are arguably dependent on information based on local knowledge, and experiences of de...