1

WHAT IS DISTINCTIVE IN COMMUNICATION RESEARCH?

Patrice M. Buzzanell and Donal Carbaugh

The nature of communication research is often a topic of discussion among people who have various interests in it. As individuals who study and live their academic lives, communication researchers periodically ponder what makes their scholarship distinctively communication research. In other words, are there qualities that set their research in communication apart from that, for example, in social psychology, linguistics, sociology, anthropology, or psychology? Over the history of communication studies, there have been numerous attempts to define and position the contributions of communication scholars as unique. Some of these identify researchers’ interests in the content of and ways in which verbal and nonverbal messages operate. Others sustain interests in varieties of discourse (ranging from micro-practices through macro-societal narratives). Whatever the focus, collections of essays and review articles over the years attest to the difficulty of pinpointing exactly what communication brings to the table in scholarly enterprises as well as in academic life generally.1 Perhaps the most satisfactory responses to the question are embedded in individual researchers’ programs of study, or within particular scholarly traditions.

In order to address the question of what may be distinctive in communication research, we have brought together a range of scholars with exemplary research programs in the study of communication.2 We have asked each to respond to the question: What characterizes your scholarship as communication research? In other words, how does your type of inquiry treat communication not simply as data, but as its primary theoretical concern? Their responses are the heart of this book.

The resulting edited collection, Distinctive Qualities in Communication Research, comes at a particularly opportune time. As in all scholarly fields, ours asks now, and periodically, what is its main subject area, or its contribution to the study of any subject area? In an era of budget cuts and surveys of departments’ reputations, deans and administrative leaders sometimes ask what a department of communication offers that is distinctive in its conception and conduct of inquiry. Funding agencies such as the National Science Foundation (NSF), the National Institute of Health (NIH), the Social Science Research Council (SSRC), and so on read proposals and may ask what a communication study contributes to particular social issues and/or funding initiatives that other stances for inquiry may not. A similar exigency is created by a call in many quarters for research teams from multiple disciplines to address a social problem such as AIDS, the removal of dams, environmental assessments, or issues of security and privacy. What does a communication researcher add to such a team? Each such moment provides an opportunity for communication researchers to say what is distinctive about their communication research—its philosophy, theory, methodology, and/or findings.

THE FOLLOWING ESSAYS

Six well-known scholars from the field offer a diverse set of viewpoints on our primary question: Leslie Baxter (University of Iowa), Stan Deetz (University of Colorado Boulder), Michael Hecht (The Pennsylvania State University), Joseph Cappella and Robert Hornik (University of Pennsylvania), and Gerry Philipsen (University of Washington).

In Chapter 2 “A Dialogic Approach to Interpersonal/Family Communication,” Leslie Baxter describes her position that the unique vantage point of communication lies not in understanding communication as mere phenomena nor in the methods for studying it, but in the conceptualization of communication with an emphasis on the “interdependence of messages.” Using a dialectical theory of discourses, she illustrates how her approach works to generate insights about teen talk about alcohol use during pregnancy, as well as discourses within step families.

In Chapter 3, Stan Deetz discusses “extraordinarily important social problems” about which communication scholars are and should be interested. He advocates an important conceptual shift from topical areas such as identity, power, and institutions, to re-conceptualizations of communication as constitutive of these phenomena, seeing each as an outcome of a communication process itself. His discussion illustrates some of the benefits of treating, for example, power as a dialogic, conversational, and/or discursive practice. Deetz calls his approach a “politically informed social constructionism,” and with it he re-locates traditional concerns within communication processes so to help us understand the constitutive power of communication. This process and power, he argues, shape significant features of social life such as the ways decision-making forms relations within and among polities, organizations, and nations.

In Chapter 4, Michael Hecht notes several strengths that communication brings to important social problems such as health campaigns, an area in which he has received considerable funding. He understands communication to be “culturally situated message design and interpretation.” His focus on cultural communication and indigenous practices generates insights, through participants’ stories, into particular groups’ sense-making about health, treatment, and message-centered interventions themselves. What has held communication researchers back from funding opportunities, according to Hecht, has been the lack of a grant-getting culture, low aspirations, lack of departmental resources and staff, self-perceptions as teachers and providers of service to campus members (rather than researchers), and the value the Communication field places on journal articles rather than other forms of research. To construct viable remedies for these issues, Hecht argues, communication researchers need to extend their training, understand and conduct large-scale research projects, value applied communication research, and view funded research not only as procuring economic resources but as a way to advance communication research as a means to solving important social problems.

In Chapter 5, Joseph Cappella and Robert Hornik focus specifically on communication research as a “practical science,” as a rigorous study of “messages and their specific consequences.” These authors describe message design with attention to multiple public or target audiences. They discuss particularly how communication research can address the demands in recent funding programs at the National Institute of Health and the National Science Foundation. In the exposition, Cappella and Hornik powerfully demonstrate how a scientific approach to communication achieves theoretical, practical, and social objectives. These are illustrated with current funded projects devoted to health education and cancer research. Although members of the communication discipline may have similar interests to researchers in other fields, the unique aspects of communication inquiries, according to Cappella and Hornik, lie in careful message design as one class of interventions. For instance, the ways in which health care professionals might design actual messages to save lives would be an area in which the field has an important tradition and one that encourages funding agencies to support a communication scholar within a multidisciplinary team.

In Chapter 6, Gerry Philipsen proposes that some communication researchers might think too small, and may benefit, indeed, from linking their thinking about communication to cultural features and forms. He encourages scholars to figure out how to work with others from different disciplines and from various cultural communities in mutually productive ways. He demonstrates how a network of ethnographers of communication is doing just that. In his own research, he has not only analyzed but engaged in the discourses of different disciplines. For example, he worked with a physical scientist to unveil better ways of speaking in elementary science classes. He reviews similar accomplishments of other ethnographic works in settings of health, in groups of immigrant peoples, in nanotechnology laboratories, and in various communities around the world through a Security Needs Assessment Project. Through this type of ethnographic inquiry, he surveys how this network of scholars has developed theories for understanding communication as a cultural and interactional phenomenon. For Philipsen, a central problem that communication researchers sometimes confront in a community of non-communication scholars is a lack of traction, so to speak, in talking about Communication itself as a discipline of thought. In this sense, there is sometimes a productive tension between the disciplinarity of Communication and the ways other scholars understand it as a subject matter, and the relation of that to their perspective on difficult social problems. His chapter shows a broad range of theoretical and practical applications of a communication view to such difficult problems.

A CAVEAT AND MORE

We readily admit that there are only five distinguished scholars whose views are represented prominently in this volume. If we had approached the content of this book differently, we might have divided the chapters according to (a) contexts; (b) meta-theoretical traditions; (c) communication dimensions; (d) dialectics of theory-practice and/or scholarship-activism; and (e) agency-voice dynamics. We conclude this section with (f) specific caveats and other possibilities that suggest alternative organizing logics for our book.

First, we could have organized contextually, that is, through interpersonal, intercultural, organizational, mass, or other situations of communication. However, as these scholars show us, it is only through crossing contexts and examining the processes that converge and diverge around central questions about how communication is formative of any given setting that we come to specific conceptualizations about the nature of communication. It is a focus on these and their distinctiveness which provides the central theme of this book.

Of course, we can look to earlier schemes for depicting our field. Second, we could use Robert Craig’s (1999) meta-theoretical framework. Using this, Craig’s taxonomy, we could have included rhetoric (and the arts of suasory expression), semiotics (the study of signs, symbols, their reference and the relationships and the webs of meaning that get built through sign systems), phenomenology (the study of people’s lived experience in the world, the nature of consciousness and conscious engagement in the world), cybernetics (the study of systems or overlapping, nested systems of interrelated elements that are interdependent with one another), social psychology (the study of social, and societal bases of identities and relationships), a socio-cultural studies scholar (the study of distinctive processes of meaning-making and the critical reflection on those means), and a critical theorist (the systematic critique of dis/empowering presuppositions). As we reflect upon Craig’s framework, however, we think the scholars whose works are included in this volume touch a bit on each of these. We have, across the research programs examined here, instances of ethnorhetoric, interpretations of symbols and symbolic expression, information as captured and designed in messages, issues of social identity and interpersonal relations, a variety of cultural and critical studies. We could give more detailed accounting of each, but simply mention them here as a way of introducing a range of intellectual concerns and traditions. As a result, perhaps none of our contributors fits solely within one of these (i.e., Craig’s) traditions, rather than the others. Of course, traditional placement was not Craig’s intent. Rather, he had hoped to identify dimensions of scholarship that could enhance discussion of our field, its theories, and concerns. And it is in that spirit of engaged discussion, that we mention his seven traditions here.

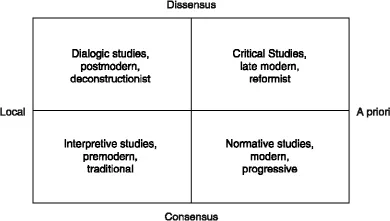

Third, we also could use Deetz’s (1996) dimensions of communication similarly, noting that we have representatives from each discourse, all the while admitting that scholarship does not fit easily within any single “quadrant”, (see Figure 1.1). We could note that Deetz aligns his critical–political view with the dissensus aspects of our field; Leslie Baxter operates within a dialogic view, while Gerry Philipsen integrates normative and interpretive modes, giving voice to individuals’ ways of speaking about their situations. Michael Hecht is, in his way, normative with critical interventions in view, while Joe Cappella and Robert Hornik adopt, primarily, a more normative and progressive stance. All of these forms of scholarly inquiry help our field construct and maintain a range of rich and diverse insights into social issues, demonstrating our field’s unique ability to emphasize process, particularly communication processes as central to the conduct of social and cultural lives. The range of approaches also demonstrates a complementary set of methodologies to the study of communication. In each quadrant and across quadrants, we see different ways of creating knowledge claims, building theory, and establishing judgments. Treating the group of approaches in this way—focused on dimensions of consensus and dissensus, comparative methodologies, knowledge claims—brings discussion of them, as with Craig’s template, to a metatheoretical level, reflecting upon how theories are constituted, what commitments are being made through each, what methodological implications emerge, and how important practical outcomes contribute to local interests as well as the larger society. The range of social problems being addressed is indeed impressive in what follows throughout this edited collection, from alcohol use and pregnancy, to step-families, to large-scale health campaigns, to power relations, to cancer treatments, and to nanotechnology and issues of national and local security.

Figure 1.1 Adapted from Deetz’s (1996) discursive spaces embodying social resources for research.

Furthermore, the discussion also indicates stances toward traditional dialectics of theory-practice and scholarship-activism—meaning that research not only provides insight about society as communicative processes, but also suggests possible directions for various types of pragmatic actions. In the following chapters, each scholar describes specific directions of application based upon the assumptions she or he makes. Each responds with concrete examples to the charge that communication research should have a social impact, can set an agenda for social change all the while embracing a range in their involvement, stances toward human participants, and the social phenomena at hand.

Fifth, we also note a range of stances toward agency and voice in the five chapters in this collection. For Leslie Baxter, Gerry Philipsen, and Stan Deetz, agency functions at interactional levels where one conversational turn or textual phase or organizational formation is implicated in another, then another, and so on. Similarly, voice operates at very personal or individual interactional levels for Baxter, at a mid- or abstract-range for Cappella and Hornick, and yet also at more political and cultural levels for Deetz, Hecht, and Philipsen. These of course are not mutually exclusive concerns, as each voice is distinct from yet can complement the others.

Finally, missing from our collection are of course many outstanding researchers and perspectives. Given a small volume, the omissions were by necessity. Our goals were not to offer a comprehensive account of all the different theories and distinctions in our field, nor to provide a comprehensive overview of a particular researcher’s work. Instead, we asked our contributors to focus on the single question of distinctive qualities in their work, as communication research, using their own program of studies as examples. In doing so, we have asked our contributors to stake out a position and to argue for the distinctively communicational aspects of their approach.

All chapter authors in our book take, as an imperative and a given, the worth of studying actual messages or ways of speaking or discourses, and do so with the belief that doing this type of research will reveal something important about human communicative capabilities and its shaping of lives. We do not include many other important programs of work in, for example, con...