![]()

1 Vocational Training

International Perspectives

Gerhard Bosch and Jean Charest

INTRODUCTION

Vocational education and training (VET) is often defined by its specific content or the purpose of training. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and the International Labour Organization (ILO), for example, define VET as ‘means of preparing for occupational fields and for effective participation in the world of work’ (UNEVOC 2006: 1). Such a technical definition seems inadequate, since university education also prepares students for the world of work and often for specific occupational fields. For professionals like doctors, teachers or lawyers, the occupational fields are sometimes even better defined and demarcated than those for vocational training. Thus the main difference between VET and higher education lies not in the preparation for work but in the earlier specialization for an occupational field and the lower social status of VET. In some countries, the low status of VET can easily be recognized if less neutral language is used, with VET being described as offering pathways for academically weaker students. The social status of VET is determined by its position not only in the education system but also in the labour market. VET certainly enjoys higher esteem in countries in which it opens up access to well-paid jobs with complex tasks and good career opportunities than it does in countries with polarized job structures and high shares of low-skill, low-paid jobs offering few career opportunities. Depending on the quality of the VET, the signals vocational certificates give to employers might differ from country to country. In some countries, they might signal competency to perform complex tasks autonomously in a broad occupational field; in others, however, they might signal that the holder is a low achiever in the school system and possesses only narrowly based skills for specific jobs.

In the past, most education and training systems made a clear-cut distinction at secondary level between general and vocational education. There are three possible reasons for the often very rigid barriers between these two systems. Firstly, the general and the vocational streams prepared pupils for different pathways. While general or academic education prepared students for college or university, VET was designed for immediate entry into the labour market (Shavit and Müller 2000: 30). Certificates of vocational training did not usually confer entitlement to further education.

Secondly, different actors are involved in the two systems. Unlike general education, vocational education and training (VET) is not usually organized as a homogenous ‘system’. VET may be provided by ‘a wide range of training institutions including state, non-governmental and private providers, each with differing interests, administrative structure and traditions. Public formal VET often overlaps awkwardly with the school and tertiary education systems, and Ministers of Education often share responsibility for VET policy with Ministries of Labour and/or Employment or others’ (UNEVOC 2006:1). In some cases, for example, the apprenticeship systems in the USA or firm-specific training of young people, there are no institutionalized links with the general education system and responsibility for training lies completely with the firm or the social partners. The state may still influence the training, not through its education ministries but by putting in place labour or product market regulations, such as licensing, levy systems or quality standards.

Thirdly, this diversity of providers and actors, and consequently also of learning places, content and standards, reflects the manifold origins and goals of VET programmes. In some cases they were set up by the state, companies or business organizations to avoid skill shortages. The same actors might also seek to promote the diffusion of new technologies or to develop specific industries or regions. Sometimes social goals, such as the integration of weaker performers in the general education system into the labour market, have priority. Craft unions or professional organizations set standards in order to control occupational labour markets by reducing competitive pressures from less well-qualified outsiders; industry unions representing several trades may have an interest in establishing a more broadly based VET system in order to improve their members’ employment opportunities.

Because of this diversity of actors and goals, national VET systems are mostly a heterogeneous mix of tracks within and outside of the general education system. It is not possible to understand these heterogeneous systems by focusing solely on their links with the general education system. VET systems are also deeply embedded in the various national production, labour market, industrial relations and status systems. The actual mix of institutions providing VET in a country reflects the interests and strength of the various actors and the historical compromises between them. And since national trajectories differ, it is scarcely surprising that national VET systems and their institutional arrangements differ quite considerably from each other (Bosch and Charest 2008a).

In order to characterize these differences, typologies of education and training systems have been developed. For instance, Lynch (1994) groups countries according to the institutional principles around which their training systems are organized (apprenticeship system, company training, government-led training, training levies, school-based training, etc.). In particular, she notes the lack of vocational training in countries that rely more on market principles, particularly with regard to less skilled workers and small and medium-sized firms. Other typologies are based on a dualistic approach to capitalism, in which national economies are described as ‘liberal market’ or ‘coordinated market’ economies (Hall and Soskice 2001; Estevez-Abe, Iversen and Soskice 2001; Bosch, Lehndorff and Rubery 2009; Iversen and Stephens 2008). Crouch, Finegold and Sako (1999) analyze vocational education and training systems in seven countries characterized by different forms of capitalism by identifying ‘broad types’ of institutions, namely: ‘states, interest associations, local business networks, and certain kinds of firm’ (p. 8). Typologies are helpful in understanding how specific institutional settings influence the behaviour of the social actors involved in vocational training. They also help us to understand which institutions are crucial in guaranteeing the stability of the different systems. Because of their functionalist perspective, however, typologies are per se static and cannot explain the dynamics of the different systems. Thus the studies by Ashton and Green (1996) and Thelen (2004) are more pertinent to our own investigation of changes in vocational and training systems within the wider context of changes in society. They both emphasise the importance of history in understanding the main characteristics and specificities of contemporary systems seen as a product of social actors.

Differences between the vocational training and education systems of developed countries seem to be far more pronounced today than just after World War II. It has almost been forgotten that the USA, Canada, Australia and the UK, for example, had highly developed apprenticeship systems (see, for example, Marsden 1995; Thelen 2004). In Germany, the dominant role of the dual system of vocational training is a quite recent phenomenon. Up to the 1960s, the share of employees with a vocational certificate was only about 20 per cent (1964); it subsequently increased as a result of the expansion of the dual system of vocational training to a peak of about 60 per cent in the late 1980s (Geißler 2002: 339), since when it has been slowly declining.

In the last 40 years, VET systems in developed countries have become increasingly diverse. In the liberal market economies of the English-speaking world, traditional apprenticeship systems have declined in significance. At the same time, there has been an unprecedented expansion of general education at upper secondary and tertiary level, which has given employers the option of recruiting young people with good general skills and training them in the workplace in order to equip them with intermediate skills. Only in countries with strong trade unions and a tradition of corporatist cooperation (Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Denmark and Norway) have new apprenticeship programmes been successfully established in manufacturing industry as well as in the service sector. The baseline for vocational training has been raised. Vocational training at lower secondary level has been phased out and has moved to the upper secondary level with higher shares of general education and improved opportunities for continuing education. With the expansion of upper secondary education, these countries have tried to strengthen the links between general and vocational training. Their vocational training systems have not declined in significance to the same extent and, from an international perspective, seem almost like exotic blooms. This is all the more true since not only highly developed countries but also up-and-coming former developing countries, such as Korea and the Central and Eastern European countries, have adopted development strategies based largely on general secondary and tertiary education. In many cases, the weakness of their employers’ associations and trade unions leave them with little choice but to rely on statist strategies.

The consequences of the decline of vocational training systems in the liberal market economies are now evident. Many companies in such economies are now complaining of shortages of vocationally qualified labour. What is missing, between a growing share of university graduates with their largely theoretical training and a high share of workers without any training, is the intermediate tier of trained workers with both practical and theoretical skills. Many governments are trying to raise the status of vocational training. New apprenticeship systems are being established in Australia, the UK and Canada and school-based vocational training is being expanded.

After a long period of increasing diversity, are the parallel trends towards greater investment in vocational training in the liberal market economies and the expansion of general education in the coordinated market economies now leading to greater convergence? Some scholars argue that the structural shift towards services could produce greater convergence, since services require less occupational knowledge and more general skills (Castells 1996: 238). Other scholars argue that the needs of more general skills do not erode the needs for specific occupational skills (Clarke and Winch 2007; Bosch 2008). It just means that vocational training requires a broader base of general skills and that occupational skills have to be acquired together with so called ‘soft skills’.

The increased need for general skills is a major driver of the expansion of upper secondary and higher education, which in many countries has led to a blurring of the traditionally clear borderlines between VET and general education and between initial and further education and training. These changes have led to new demands to strengthen the linkages and establish parity of status and esteem between VET and general education and between VET and further education and training. There are also pressures to improve linkages between VET and the labour market, which in the past have often been organized by the unions and employers.

Given the great diversity of starting points, the same pressures pose very different challenges when it comes to restructuring national education and training systems. This volume analyzes the responses of national actors in 10 different countries to these challenges. Seven of the countries (USA, Canada, UK, France, Germany, Australia, Denmark) are developed countries. Four are usually characterized as liberal market economies and the other three as different versions of corporatist market economies. One country (Korea) has joined the league of developed countries by virtue of its impressive economic development, while the other two countries (Mexico and Morocco) are still in the process of catching up. These last three countries have also faced the additional challenge of how to support the catch-up process by reforming their national education and training processes. They have had to choose between copying the gradual development of some advanced countries or skipping certain stages of development. Due to the weakness of the social partners in these countries, they can be characterized as state-led economies.

In the following, we use OECD the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and UNESCO indicators to analyze developments in general education at upper secondary and tertiary level and the importance of VET in the countries under investigation. We then compare the main changes in the structures of VET in these countries. We will examine, firstly, the links between VET and general education and, secondly, those between initial and further vocational training. There then follows an analysis of the links between VET and the labour market, with a special focus on the role of the social partners.1

TRENDS IN SECONDARY AND TERTIARY GENERAL AND VOCATIONAL EDUCATION AND TRAINING

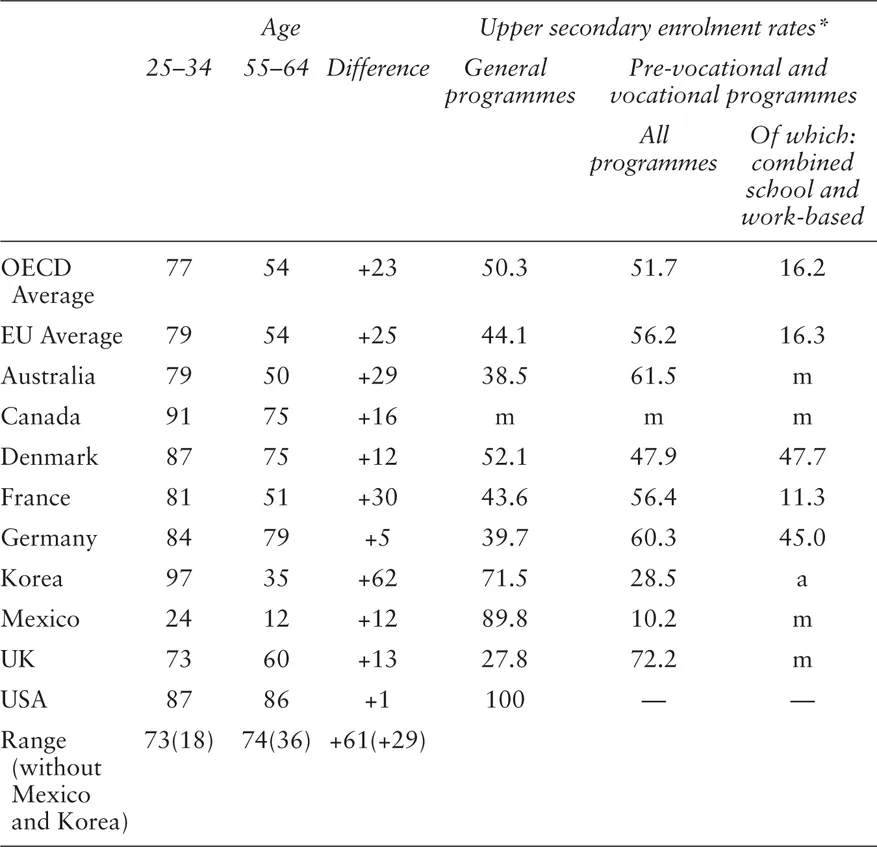

In most OECD countries, the level of general education has increased over recent decades. In 2005, 77 per cent of the adult population between 25 and 34 years had completed at least upper secondary education. This is 23 percentage points higher than the figure for the age group 30 years older (55- to 64-year-olds). In most developed countries, the level is well above 80 per cent. The range of upper secondary graduation rates is lower among 25- to 34-year-olds than for the older generation, which reflects the upward convergance of educational attainment (Table 1.1). Upper secondary certificates are increasingly becoming the minimum standard for access to the labour market and to good jobs with career prospects in all developed countries. Korea has the highest graduation rate for the 25 to 34 age group in our sample. Comparison of educational attainment in the 25 to 34 and the 55 to 64 age groups reveals how the country has effected a remarkable transition within just one generation from a skill structure characteristic of a less developed country to that of a highly developed country. Mexico and Morocco,2 in contrast, are just at the beginning of such a catch-up process. These two countries still have high proportions of the workforce and also of young people entering the labour market with even less than lower secondary qualifications.

Table 1.1 Population that has Attained Upper Secondary Education and Upper Secondary Enrolment Rates by Orientation of Programmes (2005)

Source: OECD (2007), Tables A1.2a and Table C1.1.

The increase in general education has raised the baseline for vocational training. Most young people entering vocational training have a broader initial education than in the past, which makes it possible to increase the level of theoretical learning in vocational training. The greater demand for numerical, linguistic and so-called ‘soft’ skills generated by technological innovation, combined with the increasing importance of services and changes in work organization that have devolved more responsibilities to work teams, means that many vocational programmes now require a broader theoretical base than in the past. In some countries, upper secondary certificates have become the minimum entry qualification for higher-level programmes, such as those for aspiring IT specialists or bank clerks (see the chapter on Germany in this volume). Thus in most developed countries, including Korea but excepting Australia, VET at lower secondary level has been gradually phased out. In less developed Mexico, lower secondary vocational training is still expanding in order to provide a qualified work force with lower intermediate skills for its growing manufacturing sector. For its part, Morocco has surprisingly low levels of enrolment in VET and is investing more in general education, probably because it is lacking such industries (Table 1.2).

Table 1.2 Secondary Education, ISCED 2 and 3*, Vocational Enrolments (2002)

Source: UNEVOC (2006), 70–81. http://www.unesco.org/education/information/nfsunesco/doc/isced_1997.htm (accessed 15 October 2008).