1 A brief overview of the Olympic system

This chapter takes the form of a brief presentation of the current actors within the Olympic system: the five established actors, the four new actors for whom the system has held considerable interest for some 30 years, and the three main regulatory bodies set up relatively recently.

The established actors

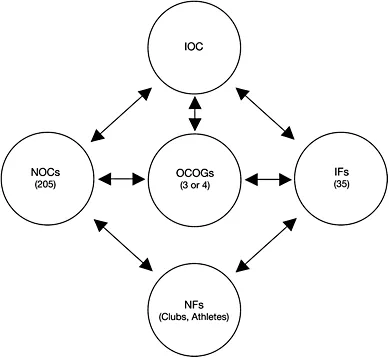

The entities that have contributed towards the preparation and running of the Olympic Games for over a century can be divided into five types of closely related actors within a robust structure. The overall term of “Olympic Movement” is used to encompass them all.

The central actor is the International Olympic Committee (IOC), founded by Pierre de Coubertin and his friends in 1894: it plays the leading role in the movement. The IOC recognizes the other actors, and partially finances them.

Despite its progressively expanding role and influence in the course of the twentieth century, the IOC’s activities remain focused on the Olympic Games, to which it holds full legal rights thanks to the worldwide registration of the numerous trademarks related thereto (interlaced rings, flag, flame, motto, etc.). For the last 30 years, those rights have generated considerable, exponentially growing income.

The IOC’s stated priority is to promote the Olympic movement and to reinforce the unity among its various entities (sport organizations) and individuals (athletes, coaches, fans, etc.) who accept the guidance of the Olympic Charter that it has drawn up. According to this charter, however, the IOC recognizes entities alone. Individuals (often volunteers) are thus only a part of the Olympic movement via their own organizations (e.g. athletes are members of their club, which is a member of their National Federation, which in turn is a member of the corresponding International Federation). The only exception to this indirect form of adhesion to the Olympic movement is that of the IOC members, since the IOC is above all an association of individuals: the men (and women since 1981) who are co-opted to this exclusive club.

The Organising Committees of the Olympic Games (OCOGs) constitute a second type of actor. Despite not being permanent—their lifespan does not exceed the around ten years required to organize a Winter or Summer Games—they are central to the system and permit it to be self-financing thanks to the revenues inherent to organizing the Games. An OCOG is created by the public authorities and the National Olympic Committee of the country concerned in the months following the designation of the host city for the Games by the IOC. The OCOG is closely linked to the local, regional, and national governments of the relevant country for all kinds of organizational issues (construction work, transport, diplomacy, police, customs, etc.). The IOC is always working with three or four OCOGs of forthcoming Games at any given point.

The International Sports Federations (IFs) represent a third kind of actor. They govern their respective sport and disciplines on a worldwide level. A distinction is made between those whose sports are on the program of the Summer or Winter Games (35 in 2008), and those whose sports are not on the program but are nevertheless recognized by the IOC (29 in 2008). There are a further 25 IFs that are members of the General Association of International Sports Federations (GAISF), founded in 1967, but are not part of the Olympic movement (i.e. recognized by the IOC).

The Olympic IFs receive part of the broadcasting and marketing rights generated by the Games. The recognized IFs receive subsidies from the IOC. The IFs’ activities are by no means restricted to the Games, but few of them organize world championships that are able to bring in major revenues of their own.

The National Olympic Committees (NOCs) represent a fourth type of actor in the Olympic system. They are the territorial representatives of the IOC, although since the IOC is not a confederation of NOCs they are independent from the IOC from a legal point of view. The IOC recognizes them as the sole entities entitled to qualify athletes from their territory to take part in the Games. In 2008, the NOCs number 205.

Like the IFs, the NOCs receive part of the rights from the Games. This distribution is, however, not carried out directly, but by means of an entity called Olympic Solidarity: a department within the IOC. The NOCs are often subsidized by their government although they are called upon to preserve their autonomy. To an increasing extent, they also serve as a “confederation of national sports federations,” with Great Britain being a notable exception.

Since 1980, the NOCs have come together within a (world) Association of NOCs (ANOC), which encompasses five continental associations facilitating the distribution of Olympic Solidarity funds. Three of these continental associations govern continental games (Pan-American, Asian and African Games).

The National Sports Federations (NFs) are the fifth and last type of actor within the Olympic movement. They unite the clubs for a specific sport in a given country and thus the licensed athletes from that country. The NFs may be recognized on a national level by the NOC of their country and/or on an international level by the IF for their sport. In some cases, this double recognition is not obtained and the athletes concerned are thus not eligible to take part in the Olympic Games.

These five different actors can be shown in the form of five rings, arranged differently from the interlaced Olympic rings (see Figure 1.1).1 The Olympic Charter, drawn up by the IOC, is the statutory basis for their actions while the athletes constitute their main raison d’être. The arrows denote the relationships among the autonomous entities that form the “classical” Olympic system.

Figure 1.1 The classical Olympic system.

The new actors

All the actors within this system, including the IOC, are non-profit organizations in accordance with the legislation of the country in which they have their registered offices.

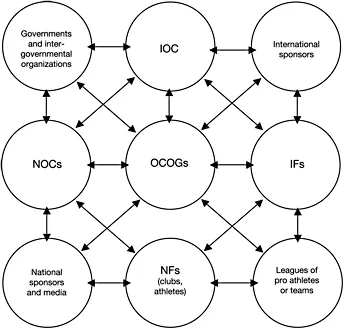

Over the last 30 years however, these actors have, to an increasing extent, interacted with four further types of actors with a legal form that differs from their own.

Governments and inter-governmental organizations under public law constitute the first such actor. In recent years, the Olympic system has needed to tackle new questions of public order. In other words, the “sports order” that it has patiently built up during the twentieth century is increasingly confronted by national and international public authorities and by the legislation they edict. For example, the European Union (EU) and its member states have been particularly active regarding sport since 1995, when the European Court of Justice rendered its judgment on the famous “Bosman case” that caused upheaval within European soccer, a subject covered in Chapter 6.

The 1990s also represented a watershed for the Olympic system because of the rapid growth in problems related to doping, violence, and corruption within sport, which led governments around the world to become involved in issues that they had previously left the sports authorities to handle. (The Council of Europe, an inter-governmental organization comprising 47 European states, had been highly active in these areas since the 1970s.)

Multinationals active in international sponsoring and that maintain commercial relations with the IOC and the IFs represent another type of emerging actor within the extended Olympic system and within worldwide sport in general. Examples here are the twelve corporations belonging to the IOC’s TOP (The Olympic Partners) marketing program (which includes Coca-Cola, Kodak, Visa, etc.) and the major broadcasters and television unions (National Broadcasting Corporation and its affiliates in the USA, the European Broadcasting Union, etc.). Given the broadcasting rights they pay to the IOC, the broadcasters could be considered as sponsors to the Olympic system in their own right. They even have the power to attract other financial partners since they convey the images of the Games to the world.

National sponsors are another type of new actor, and work with their NOC, NFs, and the OCOG (where applicable) by means of sponsorship contracts restricted to a national territory. In Switzerland, for example, the soft drinks manufacturer Rivella has been sponsoring the Swiss Olympic Association and several Swiss sports federations within the NOC. The regional and national media (written press, radio, television) also fall within this category if they sponsor the national sports movement in their region or country or buy broadcasting rights to their competitions.

National and international sponsors are usually limited, profit-making companies.

Finally, there is a fourth type of actor that has been emerging strongly over around the last 20 years, in cooperation or competition with the NFs and IFs: Leagues of professional teams or athletes. This category consists of international athletes’ groups such as the Association of Tennis Professionals (ATP), the Women’s Tennis Association (WTA), the Professional Golfers’ Association (PGA) or the lesser-known Association of Surfing Professionals (ASP), Association of [Beach] Volleyball Professionals (AVP), and the Cyberathlete Professional League (CPL). Also included in this type are professional leagues for soccer or other team sports such as those present in most European countries and whose most prestigious clubs have attempted to set up continental leagues independently of the relevant European or International Federation (e.g. the “G14” uniting 18 major European soccer clubs or the ULEB Union of European Basketball Leagues).

Beyond Europe, the powerful American professional team leagues also belong to the above category. The National Basketball Association (NBA), the National Hockey League (NHL), the National Football League (NFL), the Major League of Baseball (MLB), and Major League Soccer (MLS) share a common objective, i.e. profit for their members, owners and/or shareholders. At times, the leagues cooperate with the classical Olympic system regarding the participation of their athletes at the Games.

All of the actors that we have just described, and that are peripheral to the classical Olympic system, are shown in the diagram of the extended Olympic system (Figure 1.2). The rings have been organized in this way in order to show that actors that were once distant from the Olympic system and not involved with it to a great extent or at all are today taking on a growing importance and establishing close links with the heart of the associative sports movement. The new actors are all external partners with which the classical Olympic system must now contend. Together, all nine types of actor constitute a new, expanded Olympic system. Since a system is characterized more by its interactions than its elements, we shall now present these (new) forms of interaction, beginning with those between governments and the Olympic system.

In most countries, strong relations exist between the government and the NOC since the latter selects the team that will represent the country at the Games. Since the 1960s and the independence of former European colonies, taking part in the Games has been seen as a sign of sovereignty as strong or perhaps even stronger than being admitted to the United Nations (UN). The opening and closing ceremonies of the Games are, in fact, a unique opportunity for the over 200 countries and territories who take part to draw international attention to their existence, and in a peaceful, positive manner.

Figure 1.2 The extended Olympic system.

Interaction between an NOC and its government also exists on a level of the national sports policy, since the NOC of a country is often granted a specific role that is laid down within national legislation. This is the case, for example, in France, the USA, Australia, and Switzerland.

In a great majority of countries, however, the interaction takes the form of the NOC being dependent on the government, which attributes a subsidy, largely for operating costs, to it. This is notably the case in many developing countries whose ministers appoint the NOC executives, or at times occupy the posts in person. This approach is very much contrary to the spirit of the Olympic Charter, which states that NOCs must preserve their autonomy and resist all pressures of any kind, including but not limited to political, legal, religious or economic pressures (Rule 28.2.6). In practice, however, it is extremely rare for the IOC to withdraw recognition of an NOC temporarily on the grounds of public or political interference.

It would nevertheless appear that today many NOCs are succeeding in freeing themselves from financial dependency on their governments thanks to payments from Olympic Solidarity. This income, which reaches several thousand US dollars per year even for the smaller NOCs, is intended to cover normal operating costs and is granted in addition to provision of courses to train NOC staff and the financing of (minimum) eight athletes and officials to take part in the Games. Although the amount for operating costs may appear low, it nevertheless represents a fortune in many countries. Furthermore, by joining the IOC’s TOP marketing program, the NOCs have the opportunity to earn commission in proportion to the value of the sponsoring market for their territory and the number of athletes they send to the Games.

If the Olympic Games take place on its territory, an NOC is closely involved right from the bid phase, and is entitled to participate in the OCOG. The local, regional and national governments must also become closely involved, since the Games have become a source of major changes in terms of developing land, economy and society. Hosting the Olympic Games also represents international prestige for a country. As already mentioned, the forms of interaction between an OCOG and the various levels of the state are mandatory for issues such as security, transport, customs, etc. Over time, OCOGs have thus become para-public entities within which the state—in the largest sense—plays a major role.

In the same way, the increasing importance of the Olympic Games and of sport in general has led to development in the area of relations between the IOC and governments. When the IOC was founded in 1894, Coubertin already stated a wish to see such relationships develop. His successors, however, imbued with a philosophy according to which sport had nothing to do with politics, did everything within their power to restrict such relations to a minimum. It was only as of the 1970s when it became necessary for the IOC to pay considerable attention to governments, notably because of the boycotts linked to the question of apartheid that targeted the 1972 Munich and 1976 Montreal Games. The boycotts were orchestrated by the Supreme Council for Sport in Africa (SCSA), the sports branch of the Organization of African Unity (OAU), and propagated to some extent by the United Nations Organization. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), which at the time was strongly influenced by tiersmondiste ideas, even imagined at one point that it could benefit from the IOC’s difficulties to implement a new world sports order. An International Charter of Physical Education and Sport was thus adopted in 1978 within the framework of the Member States’ first meeting of Ministers and Senior Officials Responsible for Physical Education and Sport (MINEPS).

The UNESCO’s discomfiture in the 1980s, plus intensive diplomatic activity by the IOC President in office, overcame the threats despite the last vestiges of the cold war that had led to partial boycotts of the 1980, 1984, and 1988 Games in Moscow, Los Angeles, and Seoul respectively. The media and financial success of the 1984 and 1988 Games incited a great many cities to bid for the organization of subsequent Summer and Winter Games. Governments thus began to adopt more of a stance of applicants to the IOC prior to becoming its partners within the framework of operating the OCOGs.

In 1998, problems of doping in sport led several countries, notably the United States, Australia, and certain European Union states, to call for major reforms within the IOC with regard to the governance of world sport. Setting up the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) was the subject of intensive negotiations between the IOC and the aforementioned governments, with the outcome of parity representation within the agency on the part of the Olympic movement and governments.

At the end of the twentieth century, the IOC underwent upheaval because of a scandal surrounding IOC members rigging elections of host cities. This concerned the 2002 Games in Salt Lake City but also those of Atlanta (1996), Nagano (1998), and Sydney (2000). The uproar forced the IOC to restructure in 1999, under pressure from the sponsors, media and governments. The IOC President in office was also compelled to appear as a witness before the US Congress. During the same period, governments also realized that their relations with the Olympic system required strengthening and greater institutionalization, in a more balanced way.

Relationships between the broadcasters and the Olympic system date back to the 1960s, when the first broadcasting rights were negotiated, but really gained in significance in the 1970s and 1980s. As of the Munich and Sapporo Games (1972), the OCOGs began to receive a considerable portion of broadcasting income and initiated programs to obtain sponsorship. For their part, the NOCs also launched marketing programs with national sponsors, which subsidized their Olympic teams. Similarly, the national federations for the main sports began to sign agreements with national partners.

In 1985, the IOC founded “The Olympic Programme” (TOP), later to become “The Olympic Partners.” Administered by an agency by the name of International Sport and Leisure (ISL) until 1992, it permitted the around 12 multinationals that had joined the scheme to be associated with the Winter and Summer Games for four years through their presence on the territories of all participating NOCs. In addition, the IOC authorized these same multinationals—against payment of a sum that today is of around 60 million US dollars—to use the Olympic rings and all the associated emblems and objects (posters, mascots, slogans, etc.) within their international communication operations, both prior to and during the Games.

The relations between the IOC and these multinationals thus became close, since the partners to the program provided considerable funding. Their influence has become clear within the higher echelons of Olympism, even if the IOC is reluctant to admit it. Coca-Cola, Kodak, Panasonic, and Visa have been part of this extremely exclusive club since the beginning. Some companies, however—including multinationals—prefer to deal with a specific OCOG alone. In such cases, they must negotiate with each NOC on whose territory they wish to advertize (except, of course, that of the country where the Games will take place).

Interaction between the IOC and its main broadcasters (or groups thereof) has also gained impetus since 1995, with the signature of contra...