![]()

Part I

How we got here

A roadmap to psychoanalytic theories of childhood and development

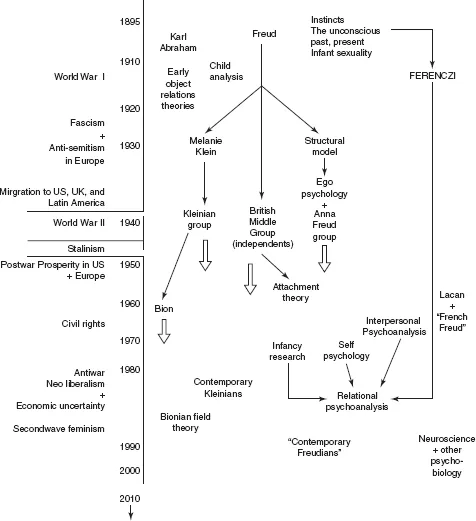

This part of the book offers a “roadmap” of sorts that sets the stage for the rest of it. It traces the evolution from Freud’s original formulations to a full-throated developmental psychoanalysis, as it developed amidst several influences—most of the traditional analytic theories, contemporary intersubjectivist and Relational psychoanalysis, psychoanalytic clinical work with adults, developmental research (especially about infants), child analysis, and infant mental health practice. In so doing, I hope to offer a basic orientation to several different core analytic theories through the window of their way of approaching childhood, child development and their relationships to adult personality, psychopathology, and psychoanalytic therapy.

While Freud established childhood as meaningful and influential in the center of his revolutionary psychology, his approach was primarily retrospective: he relied on imaginative reconstructions drawn from the fantasy-inflected memories and traumas that he considered to be the source of his patients’ pathologies. He presented childhood as embodying the disorganized primary process and asocial instincts that he saw at the primitive core of human nature. The evolution of the analytic view of childhood was influenced by members of Freud’s inner circles and other associates, including a number of women who were especially interested in children, their families, and schools; some of them remained marginal, while others became the leaders of psychoanalysis’ next generation. As Freud’s own models evolved further, he included social, growth-oriented motivations: Childhood was cast as containing endogenous, progressive, adaptive motivations parallel to the sexual and aggressive instincts. Divisions emerged between different groups of analysts around how central those adaptive currents should be in the core psychoanalytic models in general, and in clinical work in particular. At first, these centered around the Kleinian, Ego Psychological, and British Middle Groups.

Nonetheless, the central place of child development became established in much of the analytic world, analogous to physical growth, as a matter of the emerging potentials for “forward-moving” engagement with external reality and the social world; this added to a more exclusive reliance on the “backward-looking,” reconstructive method of generating hypotheses about childhood. Eventually, a more general turn toward relationships as central motivations has taken hold in the psychoanalytic scene, especially in the United States. Relational psychoanalysis and intersubjectivist Self Psychology have been especially influential, supported by the direct observation of infants and infant–parent interactions, along with other emerging historical and theoretical currents. Interpersonal analysis and innovations from Continental Europe and Latin America are increasingly garnering attention. Overall, a more flexible and multimodal approach to therapeutic technique has followed.

A narrative in context: A historical-developmental approach

Although I generally follow the standard organization of the central Anglo–American psychoanalytic orientations as they flow into the contemporary scene, this account is not meant as a positivist narrative of a field getting ever closer to some truth or scientific validity. I contextualize the changing analytic theories and their views of infancy and childhood with the different analytic cultures and organizations within which they emerged, as well as in relation to the broader historical, cultural, and economic environments, such as is possible in a brief set of chapters. As in individual development, not all the ideas, methods, and languages present at any moment are the most influential, whether implicitly or explicitly. Some are overlooked; some are suppressed or repressed; some transformed, diluted, and even co-opted. Some are marginalized, sometimes to be rediscovered later—again, implicitly as well as explicitly1.

All this has been further amplified by the extent to which analytic organizations and discourses have often been personality-driven, if not charismatically organized. These ebbs and flows are inscribed in the history of any discourse, not least psychoanalysis, as it is so located in the field of the elusive.

In a sense, I am taking a developmental perspective about the developmental orientation in psychoanalysis—seeing it as reflecting a number of different influences and environments. Changes in analytic theory do not occur in a vacuum. Just as each element in a child’s development affects and is affected by the whole person and the broader surround, the analytic view of the child has emerged in concert with the evolution of the field overall—as a movement, a clinical practice, a set of theories, an institution with its many factions and local and national organizations, and as a discourse with its own core concerns and styles. Historical and cultural contexts have always been involved, too: the place of women in the psychoanalytic establishment; the two World Wars and the rise of fascism and anti-Semitism in Europe; the subsequent emigration of Central European analysts to Britain and the United States; post-World War II prosperity, especially in the United States. I hope that this approach adds something to the many useful accounts that have been more focused on the specifics of the analytic developmental models 2.

The emergence of the psychoanalytic development viewpoint

•The origins of psychoanalysis:

•Freud’s “discovery” of childhood, in his conception of infantile sexuality and the primitive instincts, with its retrospective/reconstructive approach;

•The emergence of child psychoanalysis within the early Freudian context, led by women who were not otherwise admitted to Freud’s inner circle.

•The evolution of a new interest in early development and, finally, of a more fully developmental approach, emerging through three broad schools:

•The structural model and ego psychological approaches that developed in both Great Britain and the United States (includ-ing the postwar expansion and “expanded scope” of psychoanalysis in the United States);

•The Kleinian object relations theories;

•The Middle Group and their British object relations theories.

•The diversification and pluralization of psychoanalysis, especially in the United States, including:

•The flourishing of psychoanalysis after World War II, especially in the United States;

•The breakup of the post-Freudian hegemony and the emergence of Relationally oriented, “two-person” psychoanalyses;

•The current infant observational-intersubjective turn in the last decades of the twentieth century, with its greater interest in social interactions and direct observation of infants and their caregivers.

The psychoanalytic orientations: A timeline

Figure I.1

Notes

1This standard Anglo–American narrative has sometimes underestimated the value of the French and other Continental psychoanalytic schools. While sympathetic to this criticism, I don’t include these schools much here, as they don’t feature childhood and instead rely on retrospective approaches drawn from Freud’s earliest models. Perhaps I’m guilty of the same omission as those whom I have criticized.

2See, for example, the useful recent books by Fonagy (2001), Gilmore and Meersand (2014), Mayes, Fonagy, and Target (2007), Palombo, Bendicsen and Koch (2009), and Renn (2012), as well as classics by Blanck and Blanck (1994), Lidz (1968/1983), and Tyson and Tyson (1990). For a general overview of psychoanalytic theories, see Mitchell and Black (1995).

![]()

Chapter 1

Childhood has meaning of its own

Freud and the invention of psychoanalysis*

Psychoanalysis launched one of the great cultural revolutions of the twentieth century: childhood was now vested with meaning on its own terms and seen as the key source of adult emotional suffering and mental health. Freud’s “revelation of childhood” was one of the essential elements of this remarkable transformation: his core formulation of the childhood libidinal stages established the more general conceptualization of developmental phases. This intertwined with a model of an irrational unconscious life that was oriented to instinctual gratification. Regression and fixation to childhood traumas was at the core of his theory of psychopathology and analytic therapeutic action. Freud brought the emotional and physical experience of being a child into view in a way that changed both popular and clinical thinking.

Freud’s early models are the source of the rest of the history of analysis. Most, if not all, of the current innovations and controversies are anticipated in Freud’s work, so basic and integrated that they are easily overlooked. He saw analytic clinical practice as both a medical treatment and a research method from which he could build a comprehensive system, one that explains the widest range of human experience—dreams, sexuality, psychological suffering, family life, culture, religion, and history.1

Freud established the groundwork for developmental psychoanalysis and, in a sense, for the whole of developmental theory. Freud’s breakthroughs, though, did not comprise a fully developmental model. Freud was reliant on the retrospective method, which led him to look backward in time and “downward” in the psyche, at the expense of the more adaptive, socially oriented, and forward-moving aspects of childhood. He did not place growth and progressive change as central aspects of childhood or psychoanalytic therapeutic action. Instead, these remained secondary to the problem of taming the instincts.2

The early psychoanalytic movement led to child psychotherapy and child analysis, which emerged primarily from significant, direct engagement with children in their natural settings, mostly by women. However, many of the early child observations were not actively integrated into the analytic “mainstream” for many decades, although child analysis eventually became quite influential.

Freud’s legacy for developmental psychoanalysis: Childhood at the origins

Instincts, childhood, and the unconscious: How does a mind emerge?

Freud’s linkage of childhood, memory, unconsciousness and trauma to human joy, suffering and fulfillment remains one of the most generative ideas in our present discourse. He saw childhood as definitive in determining individual development, offering the clearest access to the basic forms and forces of personality and culture. Freud was especially interested in childhood trauma and infantile sexuality, especially during the earliest phases of his work (1895–1915). This was intertwined with his core theories of infantile sexuality and the instinctual drives, and the unconscious and repression, which emerged along with his accounts of childhood and its enduring effects. Although many readers may be quite familiar with all of this, I will offer a quick review.

Childhood, infantile sexuality, and the retrospective method: The genetic model

Freud sought to reconstruct the past from the present, especially in the patient’s symptoms, depending on the reconstructive method to search for the origins (“genesis”) of the patient’s difficulties.3 He called his retrospective-historical perspective the “genetic model.” Childhood was the key determinant of adult personality, especially childhood trauma.

In developing this method, Freud built a theory of “infantile sexuality:” childhood motivation and experience were dominated by the instinctual drives,4 organized through a series of endogenous, predetermined series of psychosexual (libidinal) stages, associated with bodily zones—oral, anal, “phallic”—to be interrupted by the quiescence of latency, followed by the surges of adolescence. The baby was the most “primitive,” psychically merged with the external environment and other people and internally disorganized, in a state of “primary narcissism.”

Bodily based instincts at the center of motivation and human nature: The dynamic-economic perspective

For Freud, the instincts are the basic source and motivation for mental life. They emerge from the body, as energic tension, pressing for discharge through whatever pathways are available—people, things, images, and so on. They thus followed the “pleasure/unpleasure principle.” Even interpersonal relationships are secondary to drive satisfaction, rather than originally significant in themselves. (Essential as it is, this idea is often overlooked by contemporary readers.) In this dynamic-economic perspective, Freud built a motivational theory along the lines of the prevailing physicalistic scientific models of his time, in which energy was seen as a matter of fluid-like forces in play: Freud saw himself as a scientist–physician and was avidly interested in scientific legitimacy. Although Freud’s view of the instincts changed over the course of his decades of writing and practice along with much of the rest of his model, these core principles remained in place, generating many of the evolving innovations and controversies.5

The unconscious as repressed and distinctively (un)structured: The topographic model

Freud, of course, placed the unconscious at the center of psychoanalysis. Most mental activity is actively repressed by the inner conscience. Further, the unconscious mental processes are chaotic and fluid, governed by the pleasure principle and thus distant from reality. Such as they are structured, unconscious “ideas” are in the relatively “primitive” forms of fantasies, dreams, raw emotions, anxieties, bodily symptoms and tensions, and the like. In most of the Freudian canon, then, “the unconscious” differs from ordinary awareness in both content and forms, such as “condensation” and “displacement.” (Some of the new models of the unconscious that have emerged recently will be discussed in Chapters 7 and 8.)

Freud (1911) proposed the term “primary process” to describe this chaotic and turbulent substrate. In his early models, he saw the primary process and the unconscious as co-located, much like the terrain (primary process) depicted in a particular place (the unconscious) on a map (hence, the topographic model). The primariness of the primary process refers both to its fundamental and temporal position, in that it is the base of mental life and came first in time.6

Overall, the intrapsychic, unconscious, instinctual factors are the most important and powerful determinants of behavior and subjective experience, especially (but not only) in childhood. In this way, Freud’s early models are not fully “developmental” in the sense in which I use the term in this book. (See Chapter 4.) The adaptive, growth-oriented processes by which the social world and the body are integrated over time are regarded as secondary.

Freud and infancy

Freud’s depiction of infancy as the most dependent, disorganized, body-based, and boundaryless...