CHAPTER 1

Assessment and values

A close and necessary relationship

Mary-Jane Drummond

There is a close and necessary relationship between what we choose to assess and what we value most in the education of our children.

In this chapter I explore a proposition made many years ago in a lecture given by Professor Marten Shipman to the Primary Education Study Group (Cullingford, 1997); he claimed that ‘there is a close and necessary relationship between what we choose to assess and what we value most in the education of our children’. The exploration opens with a story about a six-year-old child whom I knew well; his story introduces the theme of choice that runs through the rest of the chapter. My argument is that in the effective practice of assessment, educators make principled and value-driven choices about children, about learning and achievements. As a result they are able to make well-judged choices about the methods, purposes and outcomes of assessment.

Tom’s story

First, the story. Its hero is a boy called Tom who attended the school where I worked in the early 1980s, an infant school for four- to seven-year-olds, with all the trappings of the English school system, which almost alone in Europe brings very young children into institutions closely modelled on the secondary school: long corridors, cellular classrooms, sealed off with doors, daily whole school assemblies, attendance registers and a statutory National Curriculum. I was the headteacher of this school.

Tom was regarded by all the staff as a difficult child to teach, as indeed he was, due to two distinct allergic conditions from which he suffered a good deal: he was allergic to both instruction and authority. These afflictions meant that although he attended school regularly and took part in many of the activities on offer, it was always on his terms and conditions, and never as the result of a teacher’s directive. Once we had recognized the severity of Tom’s condition, we managed to find ways of co-existing, though not without frequent confrontations and highly visible incidents of various kinds. There was, in effect, a permanent power struggle taking place, around the quality of Tom’s life as he wanted to live it, and the life we wanted him to lead inside our benevolent and, we believed, inviting and challenging school setting.

The story begins when Tom was six, an age when in most of Europe children are still in nursery or kindergarten, or just beginning primary school. In contrast Tom had already had two-and-a-half years of full-time schooling and was now in the final year of key stage 1, the first stage of primary education. He was due to leave us in a few months for the next stage: a junior school on a separate site with a highly formal and rigid approach. Unfortunately for his prospects at the new school, Tom was not yet reading and writing independently. Indeed he had barely ever been known to pick up a pencil, though he loved to spend time with books, but always alone, far from the teacher’s pedagogic gaze.

One day I spent the morning working alongside the teacher in Tom’s classroom, time that included a long conversation with Tom about the model he was making with Lego. It was a massive spaceship of military design, bristling with rockets and other offensive weapons. Our conversation turned to the problem of military might and the threat of nuclear destruction. I have yet to explain that although Tom had not yet mastered the alphabet, his use of spoken language was prodigious, and he was a truly interesting person with whom to discuss current events on the social and political scene.

Back to the classroom: we talked about the possibility of global disarmament. Tom’s opinion was that the power of the arms trade made disarmament unlikely. And so we talked on, until Tom concluded the discussion with a fine summary: ‘And that’s why the world is a mess.’ My reply was, I hope, encouraging: ‘Why Tom, that would be a fine title for a book. You write it, I’ll publish it, and we’ll split the profits.’ At which point I took my leave.

Some hours later, when I was at my office desk working on some papers, I noticed Tom at the doorway. I immediately assumed the worst, that he had committed some dreadful crime against the world of school and had been sent to a higher authority to be admonished. So I was not welcoming, and Tom, in his turn, was offended and indignant. He reminded me of our earlier conversation: ‘I have come to write that book!’ I changed my tune at once and supplied him with a clean exercise book. He sat down at a table across the room from my desk, I entered the title of the book on the contents page, and at this point was dismissed back to my own work. This is the completed contents page, which he wrote some weeks later.

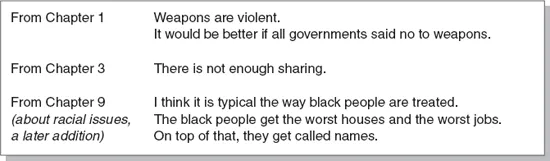

FIGURE 1.1 The contents page of Tom’s book.

[The text refers to the eight chapters of the book, thus:

- 1 and 8 is bombs

- is rubbish

- posh people

- poor people

- robbers

- vandals

- Mrs Thatcher.]

He needed a great deal of support in this production, never having written by himself before, to our knowledge. But word by word and letter by letter, Tom constructed this text. It took him many hours over several weeks: the extracts in Figure 1.2 give a flavour of his arguments.

At last the great work was complete, and Tom set off around the school to read his book to anyone who would listen. As his teachers should have predicted long before, Tom went on to flourish as both an accomplished writer and reader. It was the role of pupil he objected to, and with some reason.

Let me move on and draw out the moral of this story, with the hindsight of 20 years more experience and reflection. I now see Tom’s story as a challenging illustration of some of the crucial choices that educators face in the practice of assessment:

- choices about children and their achievements

- choices about learning

- choices about the methods, purposes and outcomes of assessment.

Choices about children

First then, I argue that we have choices to make in the way in which we construct our understanding of what it is to be a child, what sort of people we think children are and what are their most salient qualities. Obviously the choices are limitless: we are assailed by possibilities. The Japanese set us an interesting example in their chosen word for the solution to this knotty problem: they speak of a ‘child-like child’ (Kodomorashii Kodomo). A full and fascinating account of this concept is given in an anthropological study: Preschool in Three Cultures (Tobin et al., 1989), which critically explores beliefs about children held by educators in Japan, China and the USA. Other authors have more recently elaborated on this theme; for example, Dahlberg et al. (1999) offer a fascinating analysis of conflicting constructions of children and childhood, which includes a description of the child as an empty vessel, or tabula rasa, who is to be made ‘ready to learn’ and ‘ready for school’ by the age of compulsory schooling. In contrast to this child, whom the author call ‘Locke’s child’, they position ‘Rousseau’s child’, an innocent in the golden age of life. ‘Piaget’s child’ is the scientific child of biological stages, while their preferred construction is of ‘the child as co-constructor of knowledge, identity and culture’. Their argument is, like mine, that ‘we have choices to make about who we think the child is and these choices have enormous significance since … they determine the institutions we provide for children and the pedagogical work that adults and children undertake in these institutions’ (Dahlberg et al., 1999: 43). Moss and Petrie (2002) revisit these categorizations of childhood, and argue that our current constructions of children’s services are all based on the child who is ‘poor, weak and needy’. As a result, these services ‘are not provided as places for children to live their childhoods and to develop their culture’ (Moss and Petrie, 2002: 63).

FIGURE 1.2 Extracts from Tom’s book (spelling and punctuation corrected).

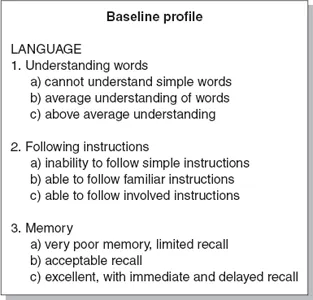

FIGURE 1.3 Extract from a baseline profile schedule.

Another way of reading and understanding our working constructions of children and childhood is by scrutinizing the instruments we use to assess their learning. My own collection of assessment schedules designed to be used with young children on entry to school, amassed over many years, suggests that the English child-like child is required to be, amongst other things, fully responsive to verbal commands and instructions: in a word, obedient.

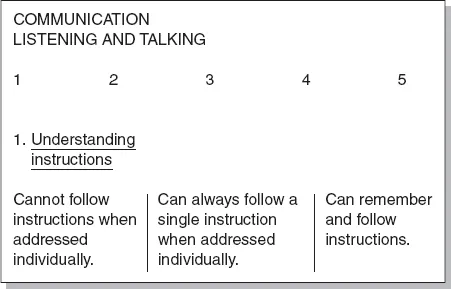

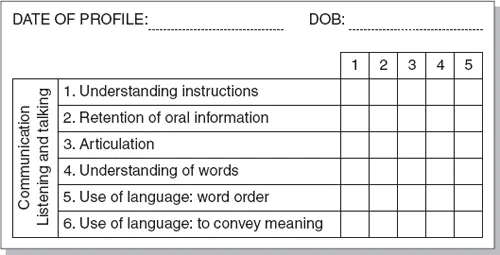

The instrument in Figure 1.3, for example, designed by a headteacher (Bensley and Kilby, 1992) to assess four-year-olds on entry to primary school, implies that language development can be assessed by observing the individual child’s capacity to respond correctly to instructions, a highly contestable view. But this example is by no means unique, as we can see in Figures 1.4 and 1.5, where the capacity to obey is explicitly prioritized as being in need of assessment.

FIGURE 1.4 Extract from an early assessment instrument

FIGURE 1.5 Extract from an early assessment instrument.

On any of these schedules, it is plain, Tom would be assessed as an entirely inadequate child, who is blatantly deviant from the expected norm. If Tom were to be assessed using the more recent Foundation Stage Profile (QCA, 2003) his strengths, for example in relation to personal, social and emotional development, would be more likely to be recognized, and his attempts at writing acknowledged.

There is another source of evidence for my claim that one prevailing concept of childhood is characterized by submissiveness and compliance: in a disturbing book, Children into Pupils, Mary Willes reports a classroom-based study, in which she followed children through their first months in school, documenting in great detail the process that transforms them from children to pupils. Her conclusion is stark: ‘Finding out what the teacher wants, and doing it, constitute the primary duty of a pupil’ (Willes, 1983: 138).

We may detect a note of exaggeration here, but only a note: the insight rings true. Willes’ argument powerfully reinforces mine: that educators may choose to construct children as seriously inadequate until proved otherwise, until they show the signs of successful pupils – obedience, attentiveness, compliance and industry. On all of these counts, Tom would not score highly, if at all. But there is an alternative. We can, if we so choose, construct our images of children in a different mould. We can choose to see them as essentially divergent, rather than convergent, inner-directed, rather than other-directed, and competent, rather than incompetent.

In recent years, we have come to associate this construction with the work of the preschool educators in Reggio Emilia, Italy, though it is important to remember it has its roots in many earlier theorists, from Dewey to Piaget, and, significantly for us in England, the great Susan Isaacs (1930, 1933), whose hallmark was that she studied children as they really are, not as some of their teachers would like them to be. Here is an illustrative passage from Carlina Rinaldi, until recently Director of Services to Young Children in Reggio, which encapsulates the Reggio position on the most appropriate way to conceptualize the state of childhood: ‘The cornerstone of our experience is the image of children as rich, strong and powerful … They have the desire to grow, curiosity, the ability to be amazed and the desire to relate to other people’ (quoted in Edwards et al., 1993).

In a more recent book, Rinaldi (2006) elaborates this distinctive theme in the Reggio philosophy, while acknowledging the influence of both Vygotsky and Piaget, and, later, Bruner, Gardner and Hawkins. She argues that ‘the image of the child’ is, above all, ‘a cultural and therefore social and political convention’, which makes it possible for educators to give children the experiences and opportunities (‘the space of childhood’, ‘a space of life’) that give value to their qualities and their potential, rather than negating or constraining them. ‘What we believe about children thus becomes a determining factor in defining the education contexts offered to them’ (Rinaldi, 2006: 83). And part of those contexts, in our own schools and classrooms, is our practice of assessment.

Now if we return to Tom’s story, and examine his learning through the lens of the Reggio ‘image of the child’, we see a very different picture. We see Tom as a child rich in knowledge and understanding, not just in terms of an extensive technical and expressive vocabulary and complex use of language, but in terms of his conceptual range and political understanding. His strength of will is remarkable, if inconvenient for his teachers; the strength of his resistance to authority cannot be denied, though we might (and certainly did at the time) wish it less strong. Tom’s powers are no less remarkable: we may note, among others, those listed in Figure 1.7 below.

Choices about achievement

And Tom’s achievements? There are choices to be made here too, i...