1 Origins and development of cognitive-behavioural therapy

With a name like yours, you might be any shape almost.

(Lewis Carroll 1872: 192)

Definition

Cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) is an evidence-based psychological approach, practised by a range of professionals, for the treatment of mental health and other personal and family problems. It seeks to help clients to analyse and ‘reality test’ existing patterns of thinking, emotional reactions and behaviour identified via an assessment of current difficulties, and to try out new approaches in a stepwise fashion, monitoring and evaluating effects in all three areas.

This will do for now, since in complex fields (this is one) definitions, though necessary, tend to be either pithy but self-referential (so that one worries about the details left out) or all-encompassing but rather like short essays in themselves. Pity the 2008 Reith Lecturer Daniel Barenboim who had to define Music. He came up with ‘sonorous air’ and then spent five hours on the complications. Adopting this approach, there follows a critical review of the main characteristics of CBT both as a collection of techniques and as a discipline.

The interrelation of thoughts, feelings and behaviour

CBT promotes rational/logical analysis of thoughts, whether in the direction of less pessimistic, less fatalistic appraisals in cases of depression; in the direction of less sanguine estimates of risk in harm reduction approaches to substance misuse or in relapse-prevention programmes in mental health. It also encourages an analysis of emotions, their circumstantial triggers, and the consequences they have for thinking and behaviour. CBT encourages clients empirically to test out their fears or avoidance reactions to see what actually happens if they react differently. Next comes a concentration on behaviour linked to problems, or which may even constitute ‘the problem’ itself. For research has repeatedly told us that the gap between insight, understanding and future action remains the largest, most underestimated obstacle to useful, therapeutically derived change. After all, are we not ourselves (usually the much less up against it) full of knowledge about semi-automatic patterns of cognitive appraisal, stereotypes, preferences, prejudices, habits; emotional over-or under-reactions; avoidant or self-defeating actions? But do we not often continue in very similar ways?

Thus the behavioural psychology principles: (1) that no one ever learned to swim through tutorials on the topic; (2) that some clients are simply unequipped by previous learning experiences to behave differently (behavioural deficits); (3) that these gaps need remedial action, and that positive reinforcement for new, trial behaviours must be arranged; (4) that whatever concomitant interpretive cognitions are implicated, when it come to evaluations of therapeutic good intentions, useful change in behaviour is the Gold Standard which gives credence to reports of changed mood or more rational patterns of thought.

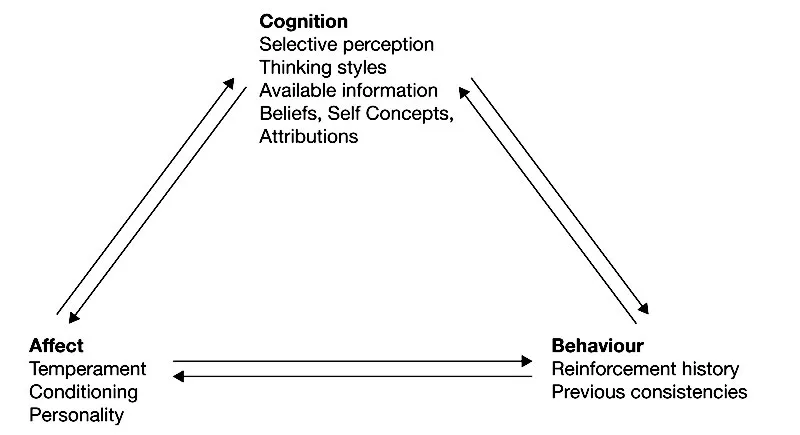

It is interesting to note in this connection how, over the decades, different schools of psychology have emphasised one or other of these three strands of human experience (see Figure 1.1). Thus, psychoanalysis held/holds that feelings, particularly repressed sexual feelings, trump everything else. The radical behaviourists held that hard-or impossible-to-verify inner experiences such as thoughts and feelings are concomitants of interaction with an ambivalent physical and social environment; and were/are a bar to scientific development, suggesting that these probably do not even exist in the forms in which they are popularly conceived (see Chapter 4; Skinner 1953, 1974). Cognitive therapists (see Beck 1976), on the other hand, see thoughts and patterns of inaccurate causal attribution as primary; as more than just the triggers and maintainers of maladaptive emotions and behaviour. Their thinking is that the other two brute elements will fall into line when these cognitions have been clarified. However, some persuasive research suggests that it may just be the other way around, and that they are underestimating the power of emotion (see Le Doux 2003).

Unreconstructed proponents of each of these schools will always react to such summaries as (hurt but coping) victims of stereotyping, but analyses of the psychological knowledge on which their disciplines rest (see Bergin & Garfield 1994; Eysenck 1978, 1985) confirm just these emphases; just these practices, just these priorities, just these blindspots. However, when psychoanalysts came to evaluate their work (if they did at all) they could not escape at least glancing at subsequent behavioural change, not just at the ‘revealing’ content of the therapeutic discourse. Similarly, behaviour therapists have always wielded much of their influence through words, interpretations and plans. The point being that in each case these other considerations were seen as subsidiary influences.

The questions for all would-be helpers considering a particular approach are therefore: (1) what are their views of the direction of causality in problems – the key element in aetiology – and (2) what factors are routinely being privileged over others? One can now encounter, oxymoronically, ‘brief, psychoanalytical therapy’ delivered by therapists who have not themselves been analysed; cognitive therapists who accompany their clients on behavioural expeditions or give ‘homework assignments’, or behaviourists who devote a considerable portion of their sessions to how clients interpret and selectively perceive stimuli – including environmental feedback from their own behaviour. This does not however alter the point that schools of psychotherapy have tended to carve up human experience to match their embedded theoretical views on the causes of problems and therefore on the priorities for interventions.

I would like to have been able to end this first foray with the sentence, ‘By contrast, CBT practitioners . . .’ but in all honesty I cannot. So I will say instead that a close reading of the literature of CBT in its academic and practice forms shows a promising trend towards the integration of these three elements, both when investigating causes and regarding the priorities of practice (see Lambert 2004: ch. 10).

This combination of targets of potential influence, plus the fact that the means by which it is sought derive from rigorous studies, and which are then themselves subjected to evaluation, places CBT in a dominant position. There is simply nothing to compare with this approach elsewhere in the literature on psycho-social interventions (see Lambert 2004; NIHCE 2005a, 2005b, 2007a, 2007b). What could stand in the way of steady consolidation and wider application then? I see two factors which might do so.

Figure 1.1 Interactions between cognition, behaviour and affect

First, we still tend to undervalue the need for a ‘logical fit’ between nature and development of research, and studies of therapeutic effects, even though its presence appears to be the best predictor of positive outcomes. An earlier generation of psychiatrists did just go ‘empirical’, i.e. they tried out approaches that seemed to work in one or another setting then casually extrapolated them to other, quite different ones and just waited to see what happened without too many concerns as to why it did. And ourselves?:

Referring to Cognitive-Behaviour Therapy by its acronym – CBT – gives the appearance of a unitary therapy, but CBT is better seen as an increasingly diverse set of problem-specific interventions. These draw on a common base of behavioural and cognitive models of psychological disorders and utilize a set of overlapping techniques, but show significant variations in the way in which these techniques are applied.

(Roth & Pilling 2008: 129)

CBT is broadening, then; the approach is increasingly in the hands of people from different professional backgrounds who emphasise different features of the model, and, it is strongly implied in the contemporary literature that this augers well for creative diversity. ‘Let a hundred flowers bloom, a hundred schools of thought contend’ (Mao Tse Tung). So long as they do freely and openly contend, that is. Research designs able to prise out worthwhile effect sizes connectable to small behavioural differences and verbal emphases among therapists are notoriously hard to pull off. One such area of ‘development’ is the increasing tendency for one or other element of the CBT model to receive additional and sometimes exclusive emphasis: most notably the cognitive component. Under the banner of CBT many practitioners have adopted an approach that might more accurately be called Cbt, just as an earlier generation clung to the known effectiveness of what amounted to cBt. We also, with the rather belated discovery of process factors by clinical psychologists (social workers have been obsessed by them for decades), see forms of attempted engagement with clients that are much closer to the ‘humanistic’ approaches of Carl Rogers, Beisteck and others (see Lambert et al. 2004; Sheldon & Macdonald 2009), cbT as it might be called. The adjectives have started to proliferate and we now have ‘ecological’, humanistic’, ‘meta’, ‘mindfulness’ and other forms advertised.

Second, a sense of novelty, and having one’s name associated with a new approach can be very reinforcing, but take note that many other disciplines have skipped down the primrose path to sectarian certainty before. Early studies of the effectiveness of social work (see Sheldon 1986) have shown that process had become all, but at the expense of outcome research. The results of the early experimental trials were disappointing to say the least (Fischer 1973, 1976; Macdonald & Sheldon 1992). Colleagues in family therapy are only now beginning to talk civilly to each other, having splintered into many different sects (e.g. Milan School, functional, structural, postmodernist), emphasising what to outsiders are not very distinctive aspects of technique, i.e. seeing everybody together. Freud (and he would have known) described similar tendencies in psychoanalysis as due to ‘the narcissism of small differences’. We should, perhaps, apply a little learning theory to these tendencies.

What environmental factors shape the behaviour of therapists? Well, the B in CBT is awkward for a start; it takes one out of the controlled conditions of the interview room and into the rain; to the school gates, into homes after 6 p.m., into the hospital, into meetings with employers, outside to see for oneself the obstacles to change present in real-life conditions. How much more professionally comfortable and ‘efficient’ (i.e. convenient) just to talk about and analyse thoughts about these contingencies and how best to respond to them. Add to these enticements the preference of modern ‘top-down’ organisations for ‘battery’ rather than ‘free range’ employees – so that staff in the helping professions now struggle to see their clients face to face for more than 20 per cent of the working week – and you have a recipe for ‘virtual reality’ therapy (see Sheldon & Chilvers 2000; Sheldon & Macdonald 2009).

Please let it be understood that I am arguing here against a general, a priori aetiology-squeezing preference; I am in favour of decisions based on a specific history and a formulation regarding which psychological and environmental factors probably hold sway in a given case. Indeed, collaboratively adjusting therapeutic content according to the client’s history and goals should be a hallmark of CBT. Thus, if a range of problems, from low self-esteem to poor relationships with one’s children, are traceable back to sexual abuse in childhood, then the cognitions regarding semi-conscious complicity that might be leading to inappropriate self-attribution and not to the machinations of the perpetrator, might mean that 80 per cent of sessions are sensibly devoted to trying to straighten out such mistaken, self-blaming thoughts. ‘I think I was a prostitute at seven’ began one client when her childhood history was probed by the present author. (Her stepfather had given her ‘pocket money’ and treats for ‘secret favours’ – she blamed herself, not him.) However, in other cases, say, in anxiety-based conditions, it is a failure to experiment with what might actually happen if fears are confronted, which might point to a predominantly behavioural approach. ‘Horses for courses’ then, not semi-automatic pre-selection of favoured emphases, should, if we were to take our own routine advice to clients, guide our practice.

Then there is the ‘look-no-hands’ effect to consider. In other words, the culturally prescribed view that the less directly related, the more distant, the less observable a set of contingencies associated with change, the greater the prestige and perceived expertise accorded to the helper. Which is why a mental health nurse exercising considerable expertise in line with a large body of research, walking a trembling agoraphobic client around a supermarket, is seen as giving technical back-up; but exploring the alleged, dark, visceral psycho-sexual origins of this fear in the consulting room is seen as more skilled. This is so even though the first approach will probably take about six one-hour sessions to complete and be very effective, and the second, three to five years, and probably make little difference other than to the client’s bank balance (see Skinner 1974; Rachman & Wilson 1980; Eysenck 1985; Lambert 2004).

We need thus to consider whether the tendency to tinker about with tried-and-trusted treatment protocols and try continually to rebrand them is always a sign of disciplinary confidence and a wish to experiment, or whether it is sometimes closer to intellectual fidgeting or empire building. True experiments to see whether the range of CBT’s effectiveness can be extended beyond its established clientele have been undertaken and sometimes the answer has been ‘not really’, or ‘a little’ (see Bergin & Garfield 1994; Lambert 2004); but then carefully controlled investigations with disappointing results are very precious so long as methodological standards have not been relaxed in the face of the worthy aspirations and the enthusiasm of participants, and that we take the lessons.

CBT is an evidence-based approach (discuss)

Above all other considerations, CBT claims to be an evidence-informed discipline, and we need to take a look at what this implies – since it must be more than a slogan. It means that practitioners should actively select a given approach because of the quantity and quality of research evidence, and not for any other reason associated with familiarity, occupational congeniality or ‘image’.

Evidence-based practice is in fact quite an old idea. Mary Richmond was writing about the obstacles to it on the eve of the Russian Revolution (Richmond 1917); the first controlled experiments on the effects of social work were undertaken in the late 1940s/early 1950s (see Fischer 1976; Sheldon 1986; Sheldon & Macdonald 2009: chs 3–4) – as early as any medical trials, but with poor outcomes. The results now, from a very much larger body of research, are much more positive, due largely to the adoption of behavioural and cognitive behavioural approaches and the principles of task-centred casework (see Reid & Hanrahan 1980; Sheldon & Macdonald 2009: ch.10).

This idea, with its own regularly changing brand names, now appears to have found its time throughout the helping professions, so let us look at the essential factors, beginning with a definition:

Evidence-Based practice is the conscientious, explicit and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the future well-being of clients.

(adapted from Sackett et al 1996).

How does this definition, adapted from the field of evidence-based medicine, translate to psycho-social approaches? The word conscientious surely reminds us of the need to give practical expression to hovering codes of ethics, particularly regarding the validity and reliability of recipes from research which we then try out on vulnerable people. There is after all no point in ‘happy-clappy’ mission statement commitments to provide non-discriminatory, non-postcode lottery-based, speedy access to ineffective help.

Hippocrates counselled his student physicians thus: ‘First, do no harm.’ Can it be said that we in the would-be helping professions, and psychotherapy in particular, do no harm? Sins of omission (e.g. blinkeredly underestimated suicide risks in mental health cases (see App...