The Ubiquity of Technology

[A] frog if put in cold water will not bestir itself if that water is heated up slowly and gradually and will in the end let itself be boiled alive, too comfortable with continuity to realize that continuous change at some point may become intolerable and demand a change in behavior.

(Handy, 1990: 9)

The boiled frog syndrome has entered the management literature as a warning to those who fail to detect environmental change and take action (Handy, 1990; Frost, 1994). Examining the reintroduction to the social world of those isolated from normal life for long periods of time enables us to detect the stark changes in them that the rest of us barely notice. Nelson Mandela’s autobiography describes how, on his release from prison in 1990 after serving a twenty-six-year sentence, a television crew “thrust a long, dark and furry object at me. I recoiled slightly, wondering if it were a new fangled weapon developed while I was in prison. Winnie informed me that it was a microphone” (Mandela, 1994: 673). After undergoing voluntary exile from the “real world” during his ten-year premiership, former prime minister Tony Blair acquired his first mobile telephone (Sky News, 2006) and had to master new competences such as learning how to use it. Such technology had become ubiquitous during his term in office and any nine-year-old might have been a knowledgeable tutor for the former premier.

Since the first edition of this book was written, terrorist attacks in North America (9/11), London (7/7), Istanbul, Madrid, Beslan, Mumbai and the Maldives, to name but a few, have had a tremendous impact, both physically and emotionally. Very human disasters have been triggered by natural events, including the South East Asian Tsunami of 2004, Cyclone Nargis of 2008 which devastated Myanmar, and the pounding of New Orleans by Hurricane Katrina in 2005. New records for high summer temperatures, with unseasonal flooding elsewhere, have seen forest fires rage across the Peloponnese in Greece while English towns were struck by flooding not experienced within human memory.

Such events grab the headlines and undoubtedly trigger business interruptions for small and large organisations alike. Given that lives are often put at risk in many crises, we have learned that such events will have a disproportionate impact upon management considerations compared to the more mundane, but more probable, interruptions likely to befall managers and their organisations. Whether the trigger is viewed as a major event or a more trivial systems failure, BCM a process intended to support organisations in building resilience and, where necessary, to recover key activities as quickly as possible in order to minimise organisational impacts and protect key stakeholders.

Tension has arisen because the focus upon great events is detrimental to the exploration of the minutiae of everyday life. This tension is also evident in the fields of BC and crisis management. Historians fall into one of at least two camps: those who are primarily concerned with the great figures of history, kings and presidents, and those who seek to better understand the experiences and practices of those everyday people who often remain nameless yet are the ancestors of the majority of us. Similarly, within this book, although reference is made to well-known incidents and recoveries, this indicates the relative ease of access to such cases whose data are available in the public domain. Conversely, the sparse reference to small businesses and mundane examples hides the fact that the value of BC is in building day-to-day resilience and the associated recovery capability.

The routines of organisational and personal life depend today more than ever upon digital tools. The developed world has seen a rapid growth in online shopping, ever more sophisticated data-mining opportunities and supply chain management. Retailers have learned how to exploit the data available from loyalty cards, enabling detailed consumer profiles to be drawn. Google provides about three-quarters of the “external referrals for most websites” reports Google Watch (2007), worrying that such dominance undermines the principles of the World Wide Web. Finkelstein (2007) suggests a threat to privacy since a wide range of internet service providers may maintain detailed records of customers’ activities and thus their interests. He also reports the allegation that Yahoo! assisted the Chinese authorities to imprison dissidents. The digital age provides an opportunity for the kind of Big Brother surveillance of which not even Orwell could conceive.

In banking, the personal touch was superseded by the telephone interface, itself increasingly replaced by internet services, and, as we turn full circle, personal banking is now being reintroduced as a “value added service”. With a plethora of goods from which to choose, customers have become more demanding and less tolerant of sloppy service or delays. As such change occurs incrementally we hardly notice it, but for those such as Nelson Mandela and Tony Blair who have been temporarily isolated, the changes associated with stepping back into the real world were immense. They were not concerned only with great events but with the humdrum minutiae of living everyday life, from shopping to speaking to friends, and using social networking technologies.

Change, fuelled by new information and communication technology (ICT), may be seen as a constant – it is estimated by award-winning scientist and futurist Ray Kurzweil that such communications technologies double their capacity and power each year, while the hardward is becoming smaller by a factor of 100 every decade (Kurzweil, 2007). Linked to this, in business the reliance on technology and on fellow members of the organisational supply chain has increased both dependencies and the potential for interruptions. The need to ensure BC is in place has never been greater.

BCM is a maturing discipline. Although its origins lie in Information Systems (IS) protection, it is evolving into a full business-wide process. Kurzweiler (2007) posits that the greater affordability and miniaturisation of technology has democratised access to technology so that no single individual remains untouched by technological change. However, this text is less concerned with the technology itself than with the concomitant changes to the organisational processes, systems and operations which new developments have made possible. Organisations are socio-technical systems, and to manage them effectively for continuity, all elements must be considered. The roots of the experiences of the three authors of this book lie in a variety of sub-disciplines, including strategy, industrial crisis and Information Systems. Inevitably, these have shaped this book and the theoretical approach to BCM. Throughout this text we use the Business Continuity Institute’s (BCI, 2007a) definition, which closely fitted our earlier definition (see Elliott et al., 2001), and has provided the basis for the definition of British Standard 25999:

This definition of BCM is firmly rooted in a crisis management approach (see Shrivastava, 1987a; Smith, 1990; Pauchant and Mitroff, 1992) and is broader in scope than more traditional approaches, which emphasise hard systems (see, for example, Doswell, 2000). The next section outlines what is meant by a crisis management approach. Then, Chapter 1 considers the strategic importance of being able to deal with crises and interruptions effectively; how “service continuity” might be a more appropriate term than “business continuity”. Finally, we examine the historical development of BCM.

A Crisis Management Approach to Business Continuity

A key part of this book’s contribution to the development of BCM lies in its crisis management approach, which underpins all aspects of this text. Such an approach may be defined as one that:

• recognises the social and technical characteristics of business interruptions;

• emphasises the contribution that managers may make to the resolution of interruptions;

• assumes that managers may build resilience to business interruptions through processes and changes to operating norms and practices;

• assumes that organisations themselves may play a major role in “incubating the potential for failure”;

• recognises that, if managed properly, interruptions do not inevitably result in crises;

• acknowledges the impact, potential or realised, of interruptions upon a wide range of stakeholders;

• clearly recognises that a crisis unfolds through a series of salient phases, often providing managers with several points at which an intervention can be made to limit the impact of the threat faced by the organisation.

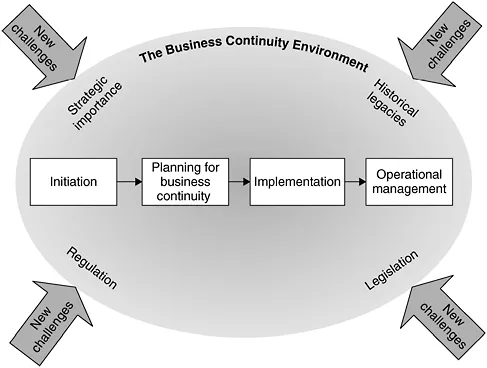

Figure 1.1 illustrates how a crisis management view of BC acknowledges first that the organisation is part of an environment characterised by uncertainty and change, leading to new challenges. Inside this environment, regulation, legislation and stakeholders help to shape the BC process within individual organisations. That process will be shaped by the historical legacy of the continuity process and the accumulated knowledge within an organisation. In addition, a key driver is the strategic

importance that business continuity management is regarded as having, both inside and outside the organisation.

Earlier BC publications (see, for example, Ginn, 1989; Andersen, 1992; Strohl Systems, 1995) have restricted their attentions to IS management and protection. More recent practical guides and case studies have a broader range of interests extending to all facilities (see, for example, Hiles and Barnes, 1999; Vancoppenolle, 1999) and, in some cases, to reputation management (Elliott et al., 1999a).

This broadening of BC reflects the underlying assumption that crisis incidents or business interruptions are systemic in nature, comprising both social and technical elements. Such a view has been well developed within the field of crisis management (Turner, 1976; Turner and Pidgeon, 1997; Shrivastava, 1987a; Smith, 1990; Pauchant and Douville, 1993; Perrow, 1997; Castillo, 2004). For example, the Challenger disaster (1986) arose from the convergence of technical failure (faulty seals) and the NASA culture. This created assumptions about the ability of staff to always succeed and the organisation became “deaf” to concerns about safety. Thus when specific safety issues were raised, the culture conspired to push ahead with the launch, resulting in tragedy (see Schwartz, 1987; Starbuck and Milliken, 1988; Pauchant and Mitroff, 1992; Vaughan, 1997). Within such a framework, the focus of disaster recovery upon the hardware is inherently flawed in that little or no consideration is given to human, organisational or social aspects of the system, nor to the interaction between components (Lewis, 2005).

Strategic Importance

The environment in which organisations operate is very complex, with change and innovation driven by increased competition and technology change. The judicious management of technology and the exploitation of Information Systems in particular are recognised as key skills which will determine organisational advantage in the “Information Society” (Bangemann, 1994, quoted in Crowe, 1996). Pilger (1998) disputes the label “information society”, arguing that “media age” is more apt and that much information is managed and filtered for good or ill. The concerns expressed by the Google Watch organisation seem pertinent here, given the data that are held by internet service providers, search engine providers and retailers about the detail of our wants and preferences. Such a view recognises that the technology which makes information processing so easy is programmed and controlled by people and organisations: that is, there are social as well as technical dimensions. This is depicted in the case of fear uncertainty and doubt (FUD) and Sun Microsystems, shown in Box 1.1.

The prominence given to the protection of IS has been highlighted earlier and forms a key consideration within this text but does not encompass the full scope of BCM. An underlying assumption of this book is that BC permeates all areas of activity. Box 1.1 highlights two high-profile “interruptions” with far-reaching consequences for the organisations involved.