![]()

Part I

Considering the issues

and the players

![]()

Chapter 1

Theory, research and practice

in mobilizing research

knowledge in education

Ben Levin and Amanda Cooper

Introduction

Knowledge mobilization (referred to in this chapter as KM) addresses ways in which stronger connections can be made between research, policy and practice. KM is an exploding field of interest, not only in education but in all areas of social policy (described more fully in Cooper, Levin and Campbell 2009). Although many different terms are used to refer to the issue (such as knowledge translation, knowledge management, research utilization, knowledge transfer and so on), all over the world governments, universities, school systems and various other parties are looking at new ways to find, share, understand and apply the knowledge emerging from research.

This chapter reviews the current situation around knowledge mobilization in education under the headings of theory, research and practice. The chapter addresses our growing understanding of and ideas about KM, considers some of the main issues in conducting empirical research in the field and looks at the state of activity to promote and increase KM, offering commentary and suggestions in each area. The chapter is based on the cumulative work of the Knowledge Mobilization Research Team at OISE through the Research Supporting Practice in Education (RSPE) programme (www.oise.utoronto.ca/rspe), which includes empirical work, conceptual work, practical activity and many connections with other researchers doing related work as well as fuller references to the conceptual and empirical literature informing this chapter.

Part 1 – Theory

What is ‘knowledge’ and what is ‘mobilization’?

Much of the writing about KM remains theoretical or conceptual, focused on different ideas of what knowledge mobilization is and how it works. Both the central ideas in the concept – knowledge and its use – have multiple legitimate meanings. Much debate in the literature concerns these different ideas about knowledge and its application.

Lomas et al. (2005) make a useful distinction between scientific evidence (which includes research on effectiveness, implementation, organizational capacity, forecasting, economics/finance and so on) and colloquial evidence (which considers professional opinion, political judgement, values, habits and traditions, and the particular pragmatics and contingencies of the situation). Our team's primary interest is in research knowledge, defined as findings deriving from widely accepted, systematic and established formal processes of enquiry. In adopting this focus we recognize that many other kinds of knowledge are also relevant to policy and practice and that research findings alone do not provide answers to all questions of practice. Moreover, the effective use of research can – and in other professions does – enhance professional status and judgment because the findings of research must be applied in particular contexts. However, we believe that greater use of research knowledge in education has the potential to improve educational outcomes in important ways (Levin 2010), just as greater empirical knowledge has led to important improvements in other areas such as health.

KM is not synonymous with research dissemination. ‘Mobilization’ is more than mere ‘dissemination’. In many ways, KM is what happens after dissemination – the discussions as well as the actions that occur beyond the basic requirement of sharing the research.

The knowledge emerging from research is not always correct and is subject to revision as time goes on, but it still, in our view, both provides good grounds for many practices and, just as importantly, can be a counterbalance to the emphasis on practitioner knowledge or conventional wisdom, both of which are regularly found later, based on systematic enquiry, to be incorrect or even harmful.

We also recognize that the ‘use’ of research has multiple dimensions. Several different typologies of research use have been proposed. The three most common uses of research from the literature are instrumental use (acting on research in specific and direct ways), conceptual use (this is more indirect; it informs our thinking) and symbolic use (to justify a pre-existing position, sometimes called political use). A fourth type of use recently emerging in the literature is imposed use, which occurs when mandates to use research evidence are applied by funders, governments or in practice settings. Nutley et al. (2007) provide an excellent review of this discussion and the many issues surrounding research use across public service sectors.

Clearly, research can and does have impact in varying ways, most of which do not involve direct application in a short time frame (though sometimes that too does occur). In most cases the effects of research are indirect and gradual, typically occurring over time as ideas get taken up and mediated through various social processes.

Research impact is, then, shaped by the larger social and political context. Think of the impact of research on current policy and practice in areas such as smoking, seatbelt use, exercise, recycling, energy conservation and so on. In all these cases, action came when there was sufficient consensus to prompt societal as well as individual action. In other cases, however, consensus does not arrive, and in that case research findings are typically subsumed in political conflict. The current debate over the science of climate change is an interesting example, in which there seems to be considerable scientific consensus but not enough political agreement to generate substantial action.

Differences in ideas about both ‘knowledge’ and ‘use’ create challenges in all areas of KM. Conceptually, one's stance on KM depends greatly on what kinds of knowledge are considered relevant. It is true that people's beliefs and actions are affected by various kinds of ‘knowing’, including knowledge of which the bearers are probably unaware. Less propositional forms of knowledge cannot be ignored if we are concerned about the realities of policy and practice. Yet if all kinds of knowledge are included, there is a danger that the discussion turns circular. The claim that practice or belief arises from knowledge of some kind seems tautological, so uninteresting. Surely what matters is the kinds of knowledge that affect what people think and do, and how those effects occur.

What are we learning about how knowledge mobilization happens?

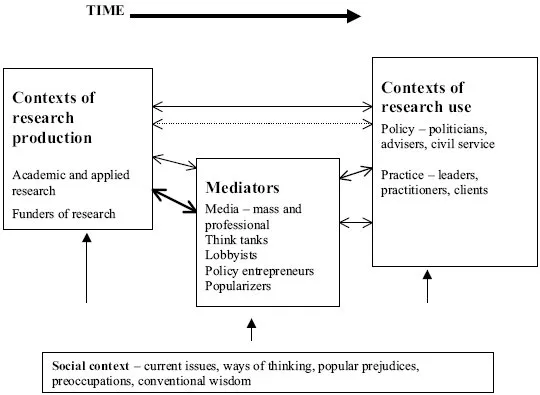

In 2002–3, Levin was a visiting scholar at the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) helping SSHRC develop its interest in knowledge mobilization. A paper written for SSHRC (Levin 2004) developed a model of knowledge mobilization highlighting three areas where this work occurs (Figure 1.1). Six years later the model remains reasonably practical and has been used or cited by quite a few others, including Nutley et al. (2009) and the European Commission (Levin 2008b). The idea of contexts of research production and contexts of research use, mediated by various intermediaries and all occurring in a wider social context, seems to have lasting value as a basic conceptualization of how KM works.

Of course KM is not as simple as the diagram. The contexts of research production and use are overlapping, not separate. Similarly, the boxes in the diagram can also represent functions and processes, not necessarily structures. Arrows represent connections and varying strength of relationships (as indicated by the two-way arrows of varying thickness). KM occurs where two or more of these contexts or functions interact. Some people and organizations operate in two or even all three of the contexts. Many other research use models exist, a number of which are available on the RSPE website. Our model differs from most others in giving equal attention to the three contexts or functions that are part of knowledge mobilization. Our model also sees research use more as a function of systems and processes than of individuals.

Figure 1.1 A model of research impact

Often different approaches to understanding research use are described in terms of a science push model (in which research producers try to disseminate their work more effectively), a demand pull model (in which users seek out relevant research), a dissemination model (where research is used due to the sheer amount of different formats available) and an interaction model (where research use occurs as disorderly interactions between groups, therefore both groups influence use – or lack of use) (Landry et al. 2001).

The simple idea that research would have direct effects on policy and practice has long been abandoned by those who study these issues, even though it may still be held by some researchers, who seem surprised or even dismayed that their work is not immediately adopted into policy or practice. However, in the last few years several other ideas about KM have become increasingly well supported from a variety of sources:

• Educators are interested in research. Although some critics attack education as a field particularly prone to valuing belief over evidence, studies (e.g. Cordingley 2009) indicate that educators express a strong interest in knowing more about research findings. They are critical of research in various ways, but they are interested. Moreover, it turns out that practice in other fields, such as medicine, also falls far short of being entirely consistent with research findings (Maynard 2007). So education is not as different from other professions as is sometimes made out, although it does lag behind health in terms of capacity and dedicated resources.

• In every field, interpersonal relationships and social contexts are the key to shaping policy and practice. People are more influenced by their own experience and by their colleagues than they are by external evidence. At the core of evidence use are interpretive processes whereby individuals and groups make meaning of evidence in ways that are profoundly shaped by their pre-existing beliefs and practices and day-to-day limits on how they direct their attention (Coburn, Honig and Stein 2009: 86). As a corollary, research products such as reports or research briefs, or even practice guidelines, while potentially valuable, do not have very much independent impact (Nutley, Percy-Smith and Solesbury 2003).

• The overall research enterprise in education remains small and weak, especially relative to the size of the sector. Most education delivery organizations, such as schools and districts, have very weak capacity to find, share, understand and apply research. Even where compelling research evidence is available, the systems for bringing it into practice are poorly developed. The same is true of many ministries of education, which seem to have weak infrastructures for inserting research into the policy process, although steps are being taken in a number of jurisdictions to improve this situation (OECD 2007).

• Many research institutions, such as universities, have rather weak knowledge mobilization efforts. Universities, the most important single source of research in education, generally do quite a poor job, especially at the institutional level, of sharing their findings or their implications. Where this work is done in universities, it is primarily the result of efforts of individual faculty members or research units. Organizations that have an explicit focus on KM, such as think tanks, tend to have much more developed processes for sharing their research.

• Significant barriers to better KM exist in both the context of research and the context of practice or policy. Barriers include skill issues (such as the ability to convey findings in plain language, or the ability to read quantitative data results), resource issues (lack of time, access to materials) and reward systems (not much push in the university to provide research relevant to educators, and not much push in the schools to read research) (for fuller discussions see Mitton et al. 2007). Another way to read these barriers, however, is that they indicate the lack of priority given to knowledge mobilization both in research-producing and research-consuming organizations. After all, nobody in a university or a school would suggest that we cancel classes because we don't have time to teach, or that we do not issue pay cheques because it's too complicated to calculate all the deductions. New activities are typically subject to a set of constraints that existing activities in the same organization do not have, even if the new activities are demonstrably more important or more valuable.

• Most of what people know about the evidence on education issues comes indirectly, through various third parties and mediators (hence the importance of this box in Figure 1.1). These intermediaries are important because they are often the ones adapting research for busy professionals and facilitating collaboration among different stakeholders; hence, they play a central role in KM. However, while there is increasing attention in the literature to mediators (Cooper 2010; Levin 2008a), there is still not a good sense of what this category comprises. The potential range of people and organizations who are in one way or another acting as mediators of research knowledge is huge, from individual practitioners or researchers to a whole range of think tanks, lobby groups, professional organizations and other bodies. Nor is it clear how mediators do their work, though it evidently involves a variety of practices from writing to speaking, to network building, to working with the media.

• Access to research has been dramatically changed by new technologies, primarily the internet. Almost anyone now has access to huge amounts of research information (and of course other kinds of information) on virtually any topic. Not only is the original research itself much more accessible, but the internet has also led to a proliferation of mediators, as anyone can now put up a communication of any kind on any topic, claiming to provide views informed by research. Moreover, what might be called legitimate producers and mediators of research, such as universities or nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) or professional bodies, rely increasingly on the internet both as their source of material and their prime vehicle for dissemination.

If one follows the logic of the above points there is clearly cause for both optimism and concern. More research is more available in more formats than ever before. Yet, because people are chiefly influenced by their colleagues and experience, because most of their knowledge comes indirectly, and because both the sharing and applying mechanisms are weak, it is highly unlikely that we are getting the maximum benefit from research in education.

It is then entirely unsurprising to find that, although the interest in empirical evidence is considerable, there are large gaps between what that evidence tells us and common practice in schools in at least some areas. One can thi...