![]()

1

INTRODUCTION

John M. Saxton

The burden of chronic disease

Chronic diseases are long-term conditions that cannot be cured but can be controlled with medication and/or other therapies (DoH 2010). Examples include coronary heart disease (CHD), stroke, cancer, chronic respiratory diseases and diabetes, which together constitute the leading cause of mortality worldwide (60 per cent of all deaths) and are projected to increase by a further 17 per cent over the next 10 years (WHO 2010). In addition to the human cost however, chronic diseases place a heavy economic burden on healthcare systems. In England, there are currently 15.4 million people living with a chronic condition (DoH 2010), accounting for more than 50 per cent of all general practitioner appointments, 65 per cent of all outpatient appointments and over 70 per cent of all inpatient bed days (DoH 2010). The treatment and care of individuals with chronic disease accounts for 70 per cent of the total health and social care costs, and this is projected to rise dramatically over the next 12–15 years as the number of people aged over 65 years increases by an estimated 42 per cent (DoH 2010). In the USA, more than 109 million people report having at least one of the seven most common chronic conditions (CHD, hypertension, stroke, pulmonary conditions, cancer, diabetes, mental disorders), representing more than half the population, and a figure which is expected to increase by 42 per cent by 2023 (DeVol and Bedroussain 2007). The total impact of these diseases on the American economy is estimated to be $1.3 trillion annually ($1.1 trillion due to lost productivity and $277 billion spent annually on treatment). Table 1.1 shows 12 prevalent chronic disease conditions.

TABLE 1.1 Twelve prevalent chronic diseases

| Chronic heart disease (CHD) Stroke COPD Depression Lung cancer Diabetes Arthritis Colorectal cancer Asthma Kidney disease Oral disease Osteoporosis |

The role of exercise in management of chronic disease

The rapidly expanding population of older people, coupled with factors such as health inequalities and poor health behaviours, means that the burden of chronic disease is an escalating problem that presents one of the major healthcare challenges of the twenty-first century. Hence, there has been a shift away from the traditional ‘medical’ model of care, with its emphasis on curative treatments and patients being regarded as passive recipients of care, to a model which is aimed at empowering patients with the skills and knowledge to manage their own condition (Carrier 2009). Evidence suggests that the majority of people with long-term conditions lead full and active lives (Corben and Rosen 2005) and over 90 per cent of people with LTCs say they are interested in being more active self-carers (DoH 2010). The need for effective self-care strategies is exemplified in the following quote taken from the UK Department of Health policy document Supporting People with Long Term Conditions: an NHS and social care model to support local innovation and integration:

When you leave the clinic, you still have a long term condition. When the visiting nurse leaves your home, you still have a long term condition. In the middle of the night, you fight the pain alone. At the weekend, you manage without your home help. Living with a long term condition is a great deal more than medical or professional assistance.

Harry Cayton, Director for Patients and the Public,

Department of Health (DoH 2005)

Although chronic diseases such as CHD, stroke, cancer, and diabetes are among the most prevalent and costly conditions in modern society, they are also among the most preventable of all health problems (CDC 2010). Major risk factors for these conditions include physical inactivity, unhealthy diets and tobacco use and the World Health Organisation estimates that by eliminating these risk factors, at least 80 per cent of all cases of CHD, stroke and type 2 diabetes and 40 per cent of cancers would be prevented (WHO website). Regular physical activity is widely accepted as being beneficial for health and a substantial body of epidemiologic research has demonstrated inverse associations of varying strength between physical activity and the risk of several chronic diseases, including CHD, stroke, hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, osteoporosis, obesity, anxiety and depression (Pate et al. 1995; Haskell et al. 2007; DoH 2004). Additionally, a growing body of research during the past twenty years has provided ‘convincing’ evidence of an inverse association between physical activity and risk of colon cancer (WCRF/AICR 2007). There is also evidence of a ‘probable’ inverse association between physical activity and risk of other cancers, including post-menopausal breast and endometrial cancer, and limited ‘suggestive’ evidence of a similar association between physical activity and lung, pancreatic and pre-menopausal breast cancer (WCRF/AICR 2007).

Aside from the important role it plays in the primary prevention of a range of chronic diseases, a physically active lifestyle can bring manifold health benefits to individuals who are carrying the burden of chronic disease. There is evidence that regular exercise is associated with physical and psychosocial health benefits in many chronic disease conditions (Pedersen and Saltin 2006) and hence, keeping fit and healthy is now promoted by government health departments as an essential element of self-care for boosting general wellbeing, improving mobility and easing of symptoms (NHS Choices 2010). A physically active lifestyle can have an important role in controlling or reducing the impact of a chronic disease, prolonging survival and enhancing overall health-related quality of life (secondary and tertiary prevention). In this respect, ‘exercise rehabilitation’ is increasingly being recognised amongst healthcare professionals as an effective adjuvant or adjunctive treatment for a growing number of chronic conditions. Table 1.2 shows some key research questions to consider when assessing the efficacy of exercise therapy as an adjuvant or adjunctive treatment for chronic disease.

| TABLE 1.2 | Some key research questions to address when assessing the efficacy of exercise therapy as an adjuvant or adjunctive treatment for chronic disease |

| Can exercise training counteract the adverse physiological and psychological sequelae of a chronic disease and its treatments? What is the role of exercise in chronic disease modification? How does exercise interact with drug treatments for chronic disease? Can exercise counteract the side-effects of drug treatments? How can exercise prescription be optimised to impact upon the broadest range of chronic disease specific health outcomes, e.g. frequency, intensity, duration and type of exercise, social setting, support structures, flexibility of provision, etc? Why do some patients with a given chronic disease respond and/or adapt differently to exercise? What are the contra-indications to exercise in different clinical groups? |

Exercise terminology

‘Exercise’ and ‘physical activity’ are terms that are commonly used in the scientific literature. Caspersen et al. (1985) proposed definitions for physical activity and exercise to provide a framework in which studies could be interpreted and compared. Physical activity was defined as ‘any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that results in energy expenditure’. Exercise was defined as a sub-category of physical activity which is ‘planned, structured, repetitive and purposive’ and which has the objective of improving or maintaining one or more components of physical fitness.

Winter and Fowler (2009) highlighted the limitations of these definitions, pointing out the shortfalls in relation to isometric exercise (static muscle actions) and argued that the two terms should be interchangeable, depending on circumstances and context. Nevertheless, exercise is more commonly used to refer to structured leisure time physical activities, such as swimming, jogging and recreational sports, rather than to common activities of daily living, e.g. walking and physical tasks in the home or work environment. The latter are more commonly categorised under the umbrella term of physical activity. For the purpose of this book, both exercise and physical activity are considered to mean any movement (or isometric exercise) of the skeletal muscles, in the context of recreational, occupational or activities of daily living, which increases energy expenditure.

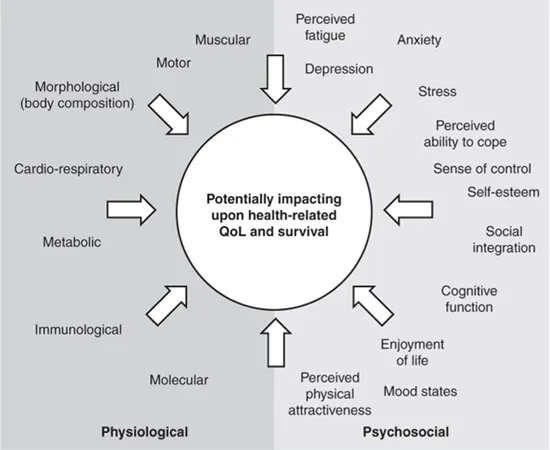

Another term that is important in the context of exercise rehabilitation is physical fitness. Physical fitness generally refers to the characteristics of an individual that permit good performance of a given task in a specified physical, social and psychological environment (Bouchard et al. 1994). It is influenced by genetic factors but is sensitive to change in people of all ages and physical fitness levels who engage in regular exercise. Physical fitness can be sub-divided into smaller measureable components, e.g. aerobic power and endurance, muscular strength and endurance, speed, power, agility and flexibility. Health-related fitness is reserved for aspects of physical fitness and psychological wellbeing that can be improved by engaging in a physically active lifestyle. In a Scientific Consensus Statement (Bouchard et al. 1994), health-related fitness dimensions were categorised into morphological, muscular, motor, cardiorespiratory and metabolic. Whilst this model includes the main physical dimensions of health-related fitness, it fails to recognise psychosocial health benefits that can result from habitual exercise. Hence, a revised model, encompassing both physical (physiological) and psychosocial dimensions which can be influenced by exercise, potentially impacting upon health-related quality of life (QoL) and survival is presented in Figure 1.1.

| FIGURE 1.1 | Physiological and psychosocial dimensions which can be influenced by exercise, potentially impacting upon health-related QoL and survival. Adapted from Saxton and Daley (2010). |

Levels of evidence

A range of methodological approaches have been used to assess the impact of a physically active lifestyle on health outcomes which are relevant to people with chronic disease. These include observational studies (mainly case control and cohort studies), randomised controlled trials and non-randomised trials. Observational studies do not investigate cause and effect relationships but associations between outcomes and ‘exposures’ of interest (e.g. self-reported physical activity) and the data should be interpreted in this context. Cohort studies (prospective and retrospective) and case-control (or case comparison) studies are commonly used observational designs. In prospective cohort studies, physical activity status is assessed at some baseline time-point before participants are followed up (often at regular intervals) to see if they reach a pre-defined clinical endpoint (e.g. disease diagnosis, cardiovascular event, mortality). The frequency with which the outcome occurs is then compared between physically active and more sedentary participants to determine their relative chances of reaching the clinical end-point. Retrospective cohort studies use pre-existing data ‘exposures’ of interest and outcomes, and are quicker and cheaper to conduct. Limitations of cohort studies include failure to account for all potentially confounding variables in the analysis (although a greater number of potential confounders can be controlled for in larger cohort studies) and the time-scale needed to follow up large numbers of people over many years (prospective studies). In case-control studies, participants are selected on the basis of their disease status rather than exposure and the main outcome measure is the odds ratio of exposure (odds of exposure in cases divided by the odds of exposure in a matched or unmatched comparison group). Case-control studies are not as scientifically robust as cohort studies and are often nested within larger cohort studies.

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) are considered to represent the ‘gold standard’ study design for establishing a cause and effect relationship between an intervention and an outcome. RCTs usually involve the random allocation of participants to an intervention group or a standard treatment control group (e.g. usual care, with or without placebo), although multiple intervention groups can also be compared with each other and the control group. This allows for the rigorous evaluation of a single variable (or complex intervention) in a defined patient group, as the assumption is that all confounding variables (known and unknown) are distributed randomly and equally between the different groups. RCTs are useful for investigating the effects of exercise interventions on key health outcomes in chronic disease populations and many examples ...